I’ve always preferred my toys broken. Something that had adventures in life before it encountered me always seemed far more valuable and interesting. This applied to affairs of the heart, especially. Strong, confident, unbroken women were always bountiful, but they had a list of suitors longer than the menu at Shoney’s.

Helping some lithesome but damaged creature find her wings again always seemed so satisfying and rewarding. It also kept me from dealing with the fact that I only ever really loved about three women, but ever telling them; that was terrifying—plus they had a choice of suitors longer than the menu at Shoney’s. Knowing that the damaged ones and the ones I truly loved sometimes read my work puts me at some peril.

I knew a boy who only wanted from life to become a writer for the US Army. While I told him that was an oddly specific career goal, the Army did indeed employ writers. They also employed filmmakers. I knew a man who got his start that way. He served under Colonel Frank Capra.

The boy was in love with a girl we all called “Boom Boom” for reasons I won’t discuss. Boom Boom was the darling of the Millsaps College English department and had a remarkably orderly, but lengthy list of suitors. My aspiring Army Novelist often used this as an excuse not to ask out Boom Boom himself, but one day he did.

“Doesn’t matter,” He said, the day after the date. “She’s a lesbian.”

The Herrenhausen family immigrated from Germany shortly before the turn of the century. They had no papers and made no application for entry; they just came, much like the Trump family.

Changing the family name to the more anglicized, Harryhausen, Fred Harryhausen had just one boy. When he was just thirteen years old, Raymond Harryhausen went to the movies with his grandmother at Grauman's Chinese Theatre. The name made no sense to him. The poster art was fascinating, though, and they had live flamingos among the rented tropical plants in the famous courtyard.

Inside, he saw a movie about an incredibly lonely prehistoric beast that fell in love with a New York girl. Grauman’s Chinese had a gimmick where they could pull the curtains back and put a special lens on the projector, making the image twice as large. This gimmick was employed to make the last reel of King Kong larger than any life ever.

On the bus ride home, young Ray decided that he, too, would make movies. This is actually very common, but in Harryhausen’s case, his parents were inventive and creative too, and they were as interested in the idea as he was. Living in Los Angeles, used and broken 16mm movie cameras and lights were readily available. Fred Harryhausen was a talented machinist and a devoted tinkerer, so a workable junior movie maker set was soon produced.

Through a girl at school, Harryhausen learned that a man named O’Brien was responsible for King Kong, so he began plotting a way to meet him. Going into his adolescent years, Harryhausen joined the Los Angeles Science Fiction club, where he met his two lifelong friends. One never quit talking and was teaching himself to speak Esperanto. The other wore extra-thick glasses and just wanted to write stories about Rocket Ships and Dinosaurs.

While Harryhausen watched King Kong, doubled in size as he pondered the blood coming out of the holes in his chest, a particularly troubled person was coming to power in Germany. The Republican led congress kept the United States from joining the war, even after Hitler invaded Poland, after Hitler began sinking English ships, and even after Hitler began sinking our ships with his dreaded U-boats.

Harryhausen was twenty-one when the US finally declared war on Germany, Japan, and Italy. Having made his own films since he was fourteen, he was assigned to the Signal Corps under Frank Capra. Working as a general technician for Capra, Harryhausen was secretly assigned to produce a 16mm film at home that changed the war.

Using model tanks and palm trees, Harryhausen produced “To Bridge A Gorge,” an instructional film on how to build a bridge using portable materials. While it didn’t win the war, it did get him in the studio door after the war, and he soon was working on his first feature film, “Mighty Joe Young.”

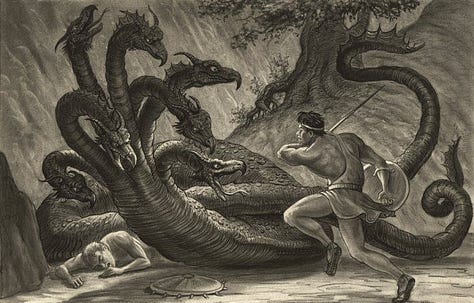

When I took “Myth” at Millsaps College, Catherine Freis enjoyed pointing out how inaccurate Harryhausen’s two films about Greek myths were. While she was right, I don’t think she knew that I had known him for about ten years at that point.

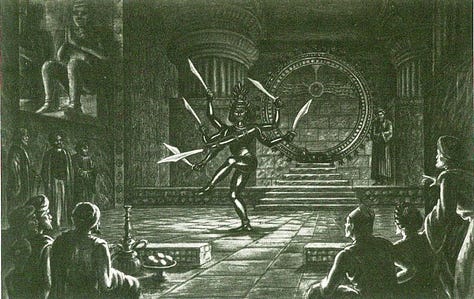

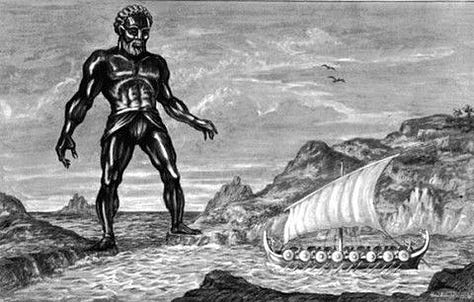

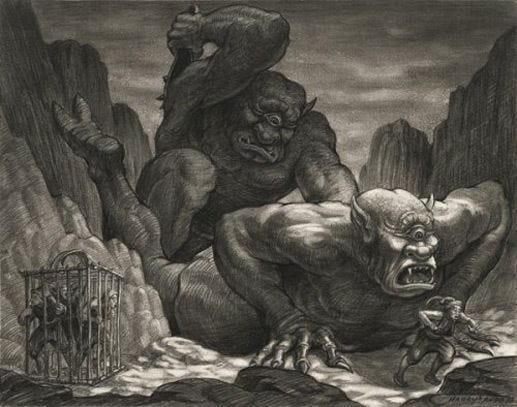

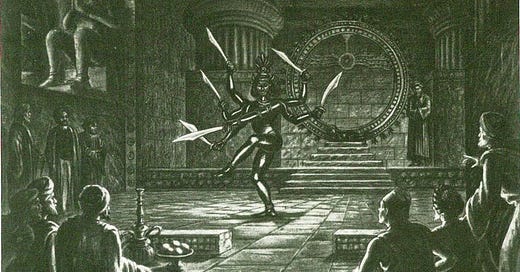

Harryhausen loved myths. He studied them from many different cultures. That’s how his film about the Ymir ended up in Rome. He also put Homer’s Polyphemus into a tale of the Arabian Nights, and changed the monster Cetus into the Norse monster, Kraken, in his movie version about Perseus.

Like Disney, Harryhausen wrote movies by drawing key scenes, then hiring an actual writer to come up with dialogue and business to get from one drawing to the next. Although he was close personal friends with two of the most notable science fiction and fantasy writers, Ray Bradbury and Robert Bloch, his films never had budgets with enough wiggle room to hire them.

A natural loner and suffering from very early-onset male pattern baldness, Harryhausen never bothered with girls much. His technique for filmmaking had him doing nearly all the work, including union work. Had he stayed in Hollywood, he would have had to hire many union workers, which would have significantly increased the film's cost and reduced his share of the profits. Therefore, he decided to move to London, where he could manage the project himself without incurring penalties.

In London, he met the granddaughter of the famous David Livingstone, who also happened to be an actual Indian Princess, several times removed. Although we had corresponded before, I became friends with Harryhausen through his wife, Dianna. She smoked, and I smoked. He absolutely did not.

Smoking together at different conventions and lectures and things, Dianna and I would discuss the best ways to keep Ray from developing more lesions on his exposed scalp that came after years of not wearing a hat while shooting scenes in exotic locations in Spain. They had a daughter, a little older than me, whom I never got to meet. I always thought that was a shame, since it occurred to me she might also be an Indian Princess with one more generation removed.

As the years rolled by, my Army Novelist from Millsaps became a transportation specialist instead. He never wrote anything, but he knew how to build a bridge in an afternoon, just like in Harryhausen’s little movie. Boom Boom, it seems, was not a lesbian. She was working on child two of a total of four she had with an accountant. One of her sorority sisters became the First Lady of Mississippi. I don’t think anybody ever called her Boom Boom.

I think we’re all broken toys. Two shy boys changed the lives of millions of shy boys around the world by telling stories about Dinosaurs, Rocket Ships, and Robots. Only one of us ended up with Boom Boom, but we all found somebody, even if they didn’t stick around.

Through the years, I’ve tried to warm Catherine Freis up to what Ray Harryhausen was doing with his movies, but she aint havin’ it. That’s ok. Her perspective on these stories is every bit as important as his, but I kinda think they’re both working from the same inspiration.