Charles Dickens wrote a novel called “A Tale of Two Cities.” Notoriously difficult to read, it begins with the sentence “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

For most of the twentieth century, Jackson, Mississippi, was the tale of two banks. That this detente didn’t carry on for another century surprised me, but not much. I watched the pirates sail into town.

In 1925, some Jackson businessmen found the lending practices of the First National Bank not generous enough. Merging three smaller entities, they found they had enough capital to compete. It was not the best time to open a bank, but they survived. In the sixties, they incorporated as Deposit Guaranty Holdings.

In bank accounting, loans to customers are considered assets. By 1980, Deposit Guaranty had the largest asset portfolio in the history of Mississippi. They also had the tallest building in Mississippi, on the same block as First National Bank, which became Trustmark, and they were connected by secret passages that weren’t all that secret. Every Christmas, the two banks would have a joint party that was lavish but restrained. That’s a concept you have to live here to understand.

By 1970, things had begun to seriously change for women in Mississippi. Evelyn Gandy, who had challenged former Jackson Mayor Leland Speed for the office of State Treasurer, was elected Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi. She would later run for Governor, but didn’t prevail. Most people have to run for Governor of Mississippi a few times before winning. A lot of people thought that Gandy could have been the first woman governor had she given it another shot.

Ten years younger than Gandy, Dorothy “Dero” Puckett was a Jackson housewife at a time when housewives were leaving the kitchen in major ways. Dero was married to Ben Puckett, who was a de facto, but not actual, member of the Capitol Street Gang, as he didn’t have a business on or near Capitol Street. Although they were photographed together a few times, that generation of the Capitol Street Gang was far younger and far more progressive than their predecessors.

A few weeks ago, Dignity Memorial sent me the notification for Dero’s funeral. “Why are they sending this to me now?” I thought. She died two years ago. When Dero died two years ago, my sister asked if I was going. I said I couldn’t. It’s uncomfortable showing up at somebody’s funeral and having to explain why you vanished for thirty years. I managed it for Sarah Jones, though. I felt like I had to.

I’m far more emotional than you would think, looking at me. That email, some sort of glitch in the Dignity Memorial system, lit a candle in me that refuses to go out. Maybe if I tell the story, or part of it, the candle will let me rest.

One of Jackson’s best cooks, Dero’s only real competition was Jane Lewis. Dero recognized that Jackson didn’t have any gourmet retail. People who wanted cooking apparatus here had the choice of Sears, McRae’s, and most hardware stores.

While the Fondren district features examples from every part of the Deco era in architecture, the Fondren Village Shopping Center was very mid-century modern, and one of my favorites. Mid-century modern should look familiar. That’s where the Jetsons lived.

Eying a detached building in Fondren Village, Dero put together a business plan, an audacious idea for housewives fifteen years before; she was more than willing to live audaciously. Like anybody else in Jackson who wanted to open a business, she went to the bank and got a loan. Being “in the bank,” she now had the eye of both banks. I don’t think she minded. She was soon in business with her girl child as second in command.

Daddy and Ben Puckett went to different schools, which should have made a difference, but Rowan Taylor was building an army of men a few years younger than him for an idea he had about a new Jackson. They became friends.

Ben Puckett provided some fairly terrifying moments at the Campbell household. The first came in 1969. In August, a monster storm descended on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Ben decided he wanted to ride it out at the home he had there. Daddy had his connections at the phone company switch the Mississippi School Supply Company WATS line from his office on South Street to our new home on the downhill border of Eastover so they could communicate during the storm.

Daddy taking a phone call alone in his bedroom was deadly serious. Often, actually deadly. As the storm intensified, even the WATS line failed. Watching the creek in our backyard begin to flood our carport while the storm stripped the trees of their leaves, we waited for proof of life on Ben Puckett. It came from his wife.

Stribling-Pucket Machinery and Mississippi School Supply Company had the same model aircraft but with a different tail configuration. I know this because a few years after Camille, theirs went down. Roger Stribling was dead. Ben Puckett was broken into a million pieces in a hospital outside of Mississippi. Upon his return to Mississippi and his return to work, people began to joke that Ben was unkillable.

Concerned about my own Daddy, Tony Staples, our pilot, explained to me what he knew about the Stribling-Puckett crash, why he thought it happened, and why it wouldn’t happen that way with him. If anything ever actually did happen to Daddy when I was little, Tony would most likely have become the Alfred to my Batman.

It turns out Dero Puckett was pretty darn good at business. While she would make subsequent loans to expand, she paid off her first loan early. She delivered the final check to the bank president personally, then visited the other bank president to make sure he knew she’d paid it off too.

Gathering for the next bank Christmas party, Daddy, Rowan Taylor, and Ben Puckett were giving Dero grief about being the only wife there. “I dunno, fellas. I’m out of the bank. Are you?” she said. “Out of the bank” meant her loan was paid off. Her business was free and clear. I knew if I laughed, I’d be considered a traitor to my gender. I didn’t care.

Brady women are pretty tough. My momma was a Brady. So was her cousin Joan. Before she actually died, there were a few times when we were pretty sure Momma would die, but she didn’t. She always considered it a test of our faith in her.

One time, Momma got pretty sick, and it kicked off cascading organ failure. She was in intensive care for over a month, and in a private room for two weeks after that.

On the Prairie Home Companion, Garrison Keelor would make fun of Methodists for their blandness, but praised their coffee and casseroles. Casseroles, I would learn, were mostly a post-war phenomenon, when housewives began finding ways to incorporate processed foods into more pleasant dishes.

When the wife is sick or dead, it’s Southern Tradition to bring the husband covered dishes, since men are considered pointless and useless in the kitchen. Even after Momma came home, we were still living off frozen casseroles for six months. They were pretty good.

Daddy had a sense of humor that got him in trouble. I get that from him. My mother had an equally devilish sense of humor, but was more subtle. It was her practice to write a sweet note on a card and leave it on Daddy’s lavatory the night before Valentine's Day. He would thank her, kiss her, leave the card on his lavatory, and have flowers delivered during the day, or I should say Phyllis, his secretary, would.

Realizing Daddy wasn’t actually reading the note inside the Valentine’s Day card, just kissing her and leaving it unread on the lavatory, she began to recycle Valentine’s Day cards. For fifteen years, he got the same card. Momma only revealed the truth a few years before he died.

“Ya know, if you’d been really sick, somebody mighta brought me a caramel cake,” Daddy said. Momma laughed, but she began plotting her response.

In his defense, a caramel cake is pretty damn good. Maybe not worth putting your wife in the hospital for over a month, but close.

Finally well enough to host dinner parties again, Momma told this story in front of Dero, Daddy, Rowan, Ben Puckett, Leon, and Jane Lewis. Everybody laughed, but the men more than the women. Daddy might have thought the story would inspire Jane Lewis, who would often gift us with baked goods. Her chocolate crepes were legendary.

A few days later, a caramel cake arrived at Mississippi School Supply Company with a note from Dero Puckett. “Happy now?”

I don’t think she would have baked for Jim Campbell when she was mad with him. The cake I recognized as most likely the product of Primos Bakery. I didn’t care. A caramel cake from Primos was pretty damn good with office coffee. The point was made.

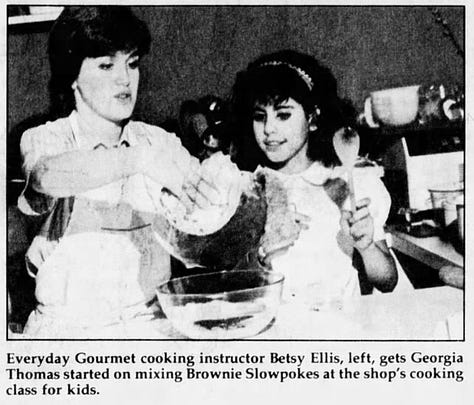

Carol Puckett does a radio show with Malcom White that’s superficially about food, but is really about the people of Mississippi. She was an excellent captain for Everyday Gourmet. Recently, John Horhn announced her as a member of his transition team as the new mayor of Jackson.

She closed the Fondren location of Everyday Gourmet, and a younger fella with a company called Swell-O-Phonic moved into the Mid-Century Modern landmark building. He doesn’t sell gourmet supplies or gourmet foods. He runs a screenprint operation that trades in all the graphics that represent Jackson’s history. Food translates culture. Art translates culture. T Shirts with “Cherokee Drive-in” on them translates Jackson culture.

One day, I’ll tell the story of why Jackson is no longer “a tale of two banks.” It’s not because Trustmark vanquished their competition. I don’t think they would have if they could have. It was never that kind of competition.

Daddy got a caramel cake. Daddy’s gone. Momma’s Gone. Dero’s gone, and Ben is gone. Tony the pilot is gone. A company that sends out email notices for funerals sent me one two years late. It made me cry.