One of my core beliefs is that every human being has something they’re uniquely good at. You can credit a creator for this, or you can assume it’s the result of randomly mixing billions of possible outcomes, but I’ve never met anyone who didn’t possess at least the seed of something special about them. What makes me question the creator sometimes is that not everybody discovers their special ability, and you’d be surprised how many people are never legitimately encouraged to develop it. Often, they’re told their unique gift is impractical and they should forget it.

It’s ironic that as much time as I now spend trying to promote Jackson and promote Mississippi, there were long stretches in my life when I wanted to be anywhere but here and long stretches where I didn’t care where I was, as long as I didn’t have to interact with anyone—ever.

I’m not antisocial. Children who stutter are often afraid to try and communicate, afraid they will try, and their words will break or come out in a way they don’t mean. Children with ADHD are often told they’re “bad,” “inattentive,” and incorrigible in other ways. Children with ADHD aren’t inattentive. They’re often hyperattentive. Even if they manage to sit still, their minds are desperately trying to balance their attention to everything in the room, including the teacher. We can’t block out everything in the room, but the teacher, and that’s how we get in trouble. I’ve had people get pretty mad about that.

It’s very difficult to escape your parents' influence. They’re older than you, and they know more than you. They love you, and they want you to be successful, even if they never agree with you on what “successful” means.

My parents had conflicting goals for me. The first happened before I was born. Should I be a girl, they were going to name me for my aunt in Atlanta. Should I be a boy, they would give me a double name for both my uncles. Had that happened, the trajectory of my life would have been very different. I would have been born without anyone having any expectations of what a John-Allen Campbell might be like.

That didn’t happen. My uncle Boyd’s cancer spread quickly. My mother was going through quite a lot when she was pregnant with me. Having lost her previous pregnancy with twins, there were times when the doctors couldn’t hear my heartbeat. Boyd Campbell was more than just the paterfamilias. At a time when Mississippi was hammered by the depression and desperately trying to escape the abject poverty we’d endured since the Civil War, Boyd Campbell, as the President of the US Chamber of Commerce, was traveling around the world, representing the newly successful “American businessman.” At a time after World War II, the American Businessman was seen as the model for the savior of the world, and this man from Mississippi, of all places, would be their face to the world.

I often try to blunt my instrument when writing about my uncle for fear that it will sound like I’m bragging. I never met the man. From what I’ve read and heard, he may have been a brilliant man, but I don’t think he was very happy. Toward the end of his life, the child he adopted moved away, his wife separated from him, he was living in a room in a hotel, and something was growing inside his body to kill him.

Whatever his success was in life, it had nothing to do with me. He died a few months before I was born. I came into this world, pink and purple, screaming loud to be heard but never wanting to be a scion. I still don’t.

There was a time when the Clarion-Ledger printed nearly every birth announcement. They did it because, even though Jackson was the capital of Mississippi, Mississippi didn’t have very many people, and we celebrated new births. By the time I was born, they had given up the practice for many years because, after the war, there were an awful lot of babies coming into Mississippi.

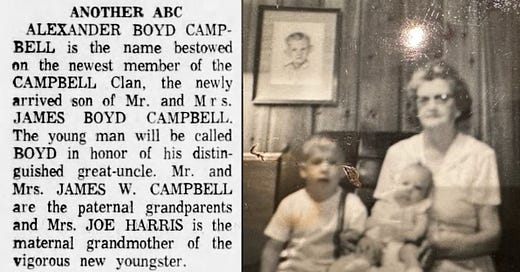

“Another ABC” The Clarion-Ledger quit running birth announcements, but they ran mine. A good ten inches, the staff writer mentioned almost nothing about me but wrote about all the things my dead uncle had done and what a great opportunity it was that I might bring that back to Mississippi. My mother clipped it out and put it in my baby book, but it was several years before I could read it. That’s an awful lot of pressure to put on an impudent baby.

You’d be surprised how many baby clothes come with alphabet blocks spelling out “ABC” on them. My mother had them all. My grandfather assumed my uncle’s position at Mississippi School Supply Company. By the time I was baptized, he had told the rest of the family that in three years, he planned to move my father into that position and step back, retaining his position as chairman of the board.

My mother’s fifth pregnancy was much simpler and easier than the previous two. Praying for a girl, even if it was a boy, she was determined this would be her last baby. With my father happy in his new position, the future looked bright. I was a very noisy toddler who never said many words but discovered ways to be heard.

Some of my Uncle Boyd's associates wrote letters to be held in my father’s lockbox at the bank until I turned eighteen. My mother told me about them when I was fourteen, making me almost dread what might be in the letters. When I finally got to read them, it was really kind of a disappointment. They just said Boyd was a great guy and hoped I would be a great guy, too.

Written in the year when I was born, the same year that my uncle died, these letters had nothing to do with me. They were old men missing their friend, who somehow transferred their affection to this rather unexceptional baby before his eyes were properly open.

In Star Trek VI, a Vulcan traitor says something I always remember. “400 years ago, on Earth, workers who felt their livelihood threatened by automation flung their wooden shoes called 'sabots' into the machines to stop them. Hence, the word 'sabotage.” She’s referencing a time during the Industrial Revolution when French weavers sabotaged the new clockwork looms.

No one expected the bit of sabotage that would wreck the world’s plans for “Another ABC.” I would imagine there have always been children with what we came to call “learning disabilities.” Still, in the years following the Second World War, Americans were intensely interested in educating our new “baby boom,” and children with learning disabilities had trouble doing just that.

On Monday, I’ll attend the funeral of one of the doctors they sent me to. He was something of a pioneer in the troubles of the brain in children. He grew to be a friend and something of a linchpin among many of my friends. In Jackson, in the late sixties and early seventies, a cottage industry of doctors, educators, and therapists who specialized in broken children grew up. I was one of their customers.

I was receiving conflicting messages from the grown-ups. One was that I must prepare to be king. Mississippi needs it, the company needs it, and the family needs it. That’s a lot of pressure for a child who didn’t want any of that, and it conflicted starkly with the second message, which was that “you’re a broken child. You must learn to overcome it, and until you overcome it, you must hide it.”

I’m actually very grateful to the people who discovered my learning disabilities. Without them, I would have just accepted it when people said I was disobedient, lazy, inattentive, and probably just stupid. Children with learning disabilities often don’t believe in their hearts that they’re stupid, but they learn to accept that prognosis from everyone else.

What didn’t happen in all of this was that nobody particularly noticed that there were things that I was actually pretty good at. There were so many things I was terrible at that they probably didn’t look for something that told a different story. When I see young people now, I immediately start looking for something special about them that nobody is seeing. It’s very lonely when the world doesn’t see your special ability. It’s easy for a child to start losing faith in the things they should have the most faith in.

At thirteen, Ray Harryhausen began teaching himself stop-motion animation, a subject that most people had no idea about. His father, a machinist, liked to tinker, so he encouraged it. They bought Young Ray second and third-hand cameras, and one fateful day, they took him to visit Willis O’Brien, who told him the legs on his clay dinosaurs looked like sausages and he should study anatomy. He went on to be one of the most influential people in the history of cinema.

For a while, some of the pressure for me to become “Another ABC” was ameliorated by my older brother. I thought he could do anything, and he had my father’s name, even though the papers never said “Another JBC.” One day, when I was just starting to get faint blond hairs on my chin, my brother’s mind broke, and another boy convinced him that it was ok to rob a gas station because the Beatles said so. They buried my brother years ago; they buried the boy who broke his life a few weeks ago.

Trying to balance my brokenness, my “place in society,” and the few things I was actually good at and enjoyed became the task of my life for the next thirty years. I wasn’t even out of college properly before offers to serve on boards started to come in. I’d been wearing ties during the day for almost five years at that point to try and hide the fact that my brain was a jumbled mess, my grades were horrible, and I wasn’t at all comfortable in the position the world was very ungently pushing me into.

I decided to quit art, quit writing, quit film and theater, and focus solely on what the world wanted of me. Quitting those things where I had meager gifts to focus on things where I had none was a pretty stupid thing to do, but young people do stupid things. That’s why God made young people strong and heal quickly.

Following this plan for ten years was a mistake, and it was also painful. Nearly every day, my father and I would discuss what went wrong and how to fix it. In his mind, that meant fixing me, not fixing how I approached life. When it started to become clear that my sister was actually good at the things my father wanted from me, I began thinking of an escape plan.

I never disliked Jackson or Mississippi. I disliked being in a place where the world’s expectations of me had nothing at all to do with what I was good at. Filling this role the world laid out for me would have condemned me to a life of mediocrity because it ignored my skills and demanded skills I never had.

When my father died, I began again thinking about my escape plan. By then, something inside me was pretty broken, though. I’d been starving my creative gifts, and while feeding them again was beautiful and wonderful, but I wasn’t at all healthy, it became a matter of too little, too late.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t kindle the spark into a flame anymore. I think there was too much scar tissue. I decided to abandon that and just open a little business importing toys from Japan and selling them to collectors in America. I didn’t have to be particularly good at business to do that. I had several exclusive deals and was good at choosing products.

I still wasn’t doing what I was made to do, though, and worst of all, I entered into a relationship with someone who really wanted me to be my dad. That happened quite a lot, actually. I’d always approached women being fairly honest about what I liked and what I was good at, but invariably, it soon became a matter of “Tell me about your dad.”

I don’t blame anyone for what happened in my life. A million times a day, people with tremendous skills and abilities die without ever having a chance to exploit them. Life keeps giving me second chances. I’m old enough that there are parts of my body that will never work again, but I’m more creative than I’ve been in forty years.

I do believe in God and that God endows every living soul with gifts only they possess. He doesn’t give us a clear path to discover and use those gifts though. That part is up to us, and that part isn’t easy. I see young people all the time who, early on, discovered their gifts, and the world celebrates them with them. I’m happy for them, and I celebrate with them, but in my heart, I’m always looking for the ones who don’t know what their gifts are yet or who do know but don’t believe in them yet.

It turns out I wasn’t “Another ABC.” That was the dream of old men who were missing their friend. Figuring out what you’re not is the first step in finding what you are. It’s often not easy. There will be signs, though. Clues and omens to help you find your way.