I have two projects I want to work on this summer and have ready for the fall. I’m not a journalist, at least not a decent one, but I want these stories to be journalism quality, so I’m going to take my time with them and do them right. Hopefully, I’ll have some help.

The first story involves my Mother, who was the first manager for Stewpot here in Jackson, but then quickly segues into the LXA chapter at Millsaps College and their now famous “Pantry Raid” program. Since we’re coming up on the forty-fifth anniversary of this program, and there are enough original participants around to make it worth doing, plus Sam Sparks might be their current faculty advisor; he was their head man like eleven years in a row when he was an undergraduate. Sometimes, when people do good, they’re not recognized for it, so I’d like to recognize it.

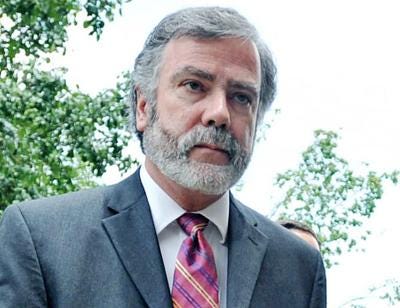

The other thing I want to do might start as a public apology to Dickie Scruggs. I used to hate Dickie Scruggs. In my mind, he was so smug and successful at suing people who brought jobs to a very job-poor Mississippi.

I used to know people who gave Trent Lott shit just for being related to Scruggs. Back in the days when I was a lot quieter about my opinion on things, more than half of my best friends ranged from very conservative to Legion of Doom. We’re still friends, and I still love them, but they’re less likely to share their thoughts with me now that I’m developing a reputation for opening my mouth.

People in Mississippi are weird. They idolize fictional lawyers like Matlock, Attacus Finch, and half the cast of the John Grisham books (and their fictionalized idea of John himself). Still, if an actual trial lawyer walked by, they’d spit three times, turn around, and cross themselves. Mississippi despises trial lawyers. I know guys whose entire campaign for public office revolved around building chains around what trial lawyers could get away with in court.

Dickie joined forces with Mike Moore. Mike was a little guy with sculpted hair and thousand-dollar suits. I’ve had three thousand-dollar suits in my life. They all happened because my shoulders got too broad for Billy Neville to dress me anymore, and I hated driving to South Jackson, where they had Capitol Menswear, because it was starting to become evident that the death of Jackson (at least Jackson as I knew it) started in South Jackson.

Mike’s suits came from Atlanta, New Orleans, or that guy at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis who would measure you ten ways to Sunday and then have you made three suits in Hong Kong. Mike had far-away eyes, not the kind that girl had in the song, but the kind that won every case they took on.

After seeking justice for shipwrights and construction workers in Mississippi, Dickie Scruggs and Mike Moore took on the tobacco industry at a time when I lived for whiskey and cigarettes. “They’ve gone too far this time!” I would say with vicious glee. “They bit off more than they can chew!” I insisted, as they won point after point, case after case, and won the world's largest settlement in the history of jurisprudence in the history of the world.

Sometimes I write a sentence, and it sounds like bullshit, but that’s not. Despite their sculpted hair and questionable haberdashery, these two boys from Mississippi won two hundred and six billion (with a B) dollars for the states where people smoked.

A couple of things changed my heart about Dickie. One is that he was personal friends with guys I idolized. When the case against Dickie and Bobby DeLaughter came up, I thought, “No way!” Bobby was low-key a hero close to my heart for a long time, even before they made that movie. When they made that movie, I laughed because they used Warren Hood’s house for a scene that took place at the Country Club of Jackson in real life.

The CCJ is a postmodern playground. You'll know why if you look at the plaque listing the building committee. Everything those men built in Mississippi was postmodern. They did it because they were running like hell from the reputation Mississippi grew during the fifties and sixties. They wanted the world to know we were no longer the antebellum South. Sometimes, people comment on the brutalism of buildings like the Ford Academic Complex at Millsaps. They used brutalism specifically because they were making a point. We’re not the old Mississippi. Rob Reiner wanted the old Mississippi, so they used locations that dripped antebellum charm, even though they made no sense compared to reality.

There’s a scene in Ghosts of Mississippi where they have some bald, thick-bodied klansman having a secret meeting among the Ruins of Windsor. When I saw it, I told my wife, “First off, he looks like me. Second off, ain’t nobody having no secret meetings at the Ruins of Windsor!” Director Rob Reiner was making a point and setting a mood. I get that, but to him, these were archetypal characters; to me, they were people who lived not far from me. I played football with Ed Peter’s boy. Boys I knew from KA had been to law school with Bobby DeLaughter. The places where they shot the movie were places I passed every day.

People talk about the power behind James Wood’s portrayal of Byron De La Beckwith. I thought it was powerful, too. In the fullness of time, we learned that Woods wasn’t just playing Byron De La Beckwith; he became him. The prosthetics became real. Look at the shit Wood’s types on Twitter if you think I’m wrong. There, I’ve said it.

For the past couple of years, I’ve been thinking they should show Ghosts of Mississippi at Millsaps and then take the kids to the John Stone house to meet Jerry Mitchell. Hopefully, the Mayflower will be open again by the fall, and they can go there too. I always thought it was funny that they hired somebody to play Malcolm McMillin in the movie. Sheriff McMillin was one of the best actors I ever knew. That was a real missed opportunity.

There’s a scene in Ghosts of Mississippi that unnerved me. In a fairly short flashback scene, a guy named Early Whitesides played Ross Barnett as he walked through the courtroom to shake hands with De La Beckwith in a clear attempt to influence the jury, which it did. The guy looked like Barnett; he walked like him and held out his hand like him. When I saw it, I touched my wife’s knee and whispered, “I don’t like this one damn bit.” Afterward, she asked me why it bothered me so much. “I’ve heard this story my whole life,” I said. “People used to laugh about it. They’d talk about how Barnett would do anything to keep himself in the spotlight.” which was true. When I was in college, Ross Barnett would play the ukelele to entertain us boys in the Old Capitol. Even then, I thought, “Man, you’re the governor of Mississippi during one of the worst times in the history of Mississippi, and now you’re playing a goddamn ukelele to make a bunch of drunk nineteen-year-olds laugh.” I thought that, but I didn’t say that. I laughed with everybody else.

I’ll say this about what happened with Dickie Scruggs and Bobbie DeLaughter, the only man born without the stain of hubris died on the cross. These men are heroes of Mississippi who made a mistake, a mistake they paid for. There was a moment where I had what they call an epiphany. When I started to count that Lance Goss, my Mother, my Father, and my Brother all died from smoking cigarettes, just those enormous losses in my life, all I can say is that Dickie Scruggs and Mike Moore were right. They were right all along.

Oh, and fuck James Woods. I know what he is. I’ve known men like him my whole life.