If my father ever said I’d have to eat an elephant, I probably would have said, “Where’s it at?”

Eating elephants was something of a family meme. It came from a joke my grandfather trotted out every time there was an unbelievably big job to do, and it seemed like there was always an unbelievably big job to do.

Daddy was pretty devoted to the idea of somehow pulling Mississippi off the bottom of everything. Part of it was his ego. Nobody likes to be associated with something that’s dead last. Part of it was his life as a Christian. Nearly everyone he cared about lived here and was trying to forge a future for themselves here, including us kids.

My father decided that there might be something in me that could help with his plot for Mississippi. He gave me some pretty unusual instructions. He told me to memorize the names of all the people in the Mississippi House of Representatives and the Senate and their committee assignments.

Bobby Moak and John Grisham were in their twenties and trying to make a name for themselves in Mississippi. John, I learned, was selling a book he had written out of the trunk of his car. I asked if I could buy a copy. It wasn’t bad. It reminded me of an updated “To Kill A Mockingbird” with more action sequences.

John’s next book was allegedly about his time in the Brunini Law firm. It wasn’t true, but that was the rumor. The legend goes that Big Ed Brunini pulled strings to get an advance copy and read it in one sitting to make sure he wasn’t in it. He wasn’t. I’ve never heard if he liked the book or not.

Unsubstantiated rumors made local sales for the book go through the roof. When his publisher saw those numbers, they realized there might be something to it, so they ramped up advertising and ordered a second printing. Next thing you know, John Grisham was on the best-seller list, and there were talks of a movie deal. I’ve heard people say he’s the most important writer in the history of Mississippi. I doubt if he’d agree with that.

A lot of the names I memorized are dead now. I got to know John Corlew again after all those years, not long before he moved from this world to the next. Cecil Brown held his spot in government as long as he could. I used to pay special attention to his daughter. Not because she was pretty, although she was, and not because she was a Chi Omega, even though I had sworn to protect them. I watched over her because of what her daddy was trying to do for Mississippi. His goals aligned with my goals.

Daddy had a reputation as a king-maker. I don’t know that it was justified. He hitched his cart to an awful lot of horses that didn’t finish the race. I used to watch him and Warren Hood eye the young men in the room, trying to decide which would break out of the pack.

I was never a break-out-of-the-pack kind of guy. I was a troubled child, but my heart was in the right place, and most people knew that.

I’ll tell you a success story and a not-so-successful story about my dad’s experience as a kingmaker. Daddy and William Winter agreed in lockstep that education was the only way up for Mississippi. In 1972, Winter became the twenty-fifth Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi.

The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 shackled the executive office because they were afraid of the cumulative voting power of black men in Mississippi. They would eventually figure out ways to keep black men from voting altogether, but in 1890, the plan was to make the Governor a weak position, which ended up making the Lt. Governor and the Speaker of the House the most powerful positions in Mississippi government.

I know stories about the Speaker of the House in Mississippi that would curl your hair. It made mine fall out. As Lieutenant Governor, William Winter had a license plate on his car that read “2”. His daughter was a few years older than me in school. She had tremendous eyes and a mouth like a Gibson girl.

Although he held the reins of power, Winter believed that the only way to enact his legislative agenda with regard to education was through the position of governor. He had run three times. Daddy and Rowan, and their crew were on board all three times, and they lost all three times. One time, they lost to Cliff Finch. That’s a pretty rough loss.

Despite the loss to Finch, Winter wanted to run again in 1978. The Finch governorship hadn’t gone well. His wife shot him in the Governor’s mansion. That’s not the official story, but it’s probably true. The Capitol Street gang opened the doors to their stable stalls and prepared for a fourth run for the governorship with William Winter at the top of the ticket. He won.

The way the 1890 constitution was written, Winter knew his governorship was a ticking timebomb that began when he put his hand on the bible and said, “I Will.” He promised to change the constitution, as many had before, but it’s been fifty years, and it’s still not changed. With a lot to do and not much time to do it, Winter put together a band of remarkable young men that even Ronald Reagan called “The Boys of Spring.” With their help, he passed nearly all of his educational agenda. One day, I’ll tell you the story about why he didn’t get all of it passed.

William Winter was undeniably a success story. Charlie Deaton, as much as I loved him, was less so. Deaton wanted to be governor more than you can imagine. He had a great agenda. He would have made a great governor. I’ll tell you a secret, though, being good at your job doesn’t mean a damn thing in Mississippi politics.

On his third time to line up for a run at the Governor of Mississippi, Rowan Taylor rented a really nice campaign headquarters for Deaton on Spengler’s corner. He had a man paint a great big “Deaton For Governor” sign on the plate glass window. Deaton himself had rented a much smaller, less expensive building to be his campaign headquarters on West Capitol. Both buildings had a one-year lease for a campaign that didn’t last a year. Deaton never ran for governor again after that. He never gave up on Mississippi, though. He ended up being a real champion for Ducks Unlimited in their efforts in the South East. They named an entire forest after him. If a fella can’t be governor, that’s a pretty good second prize.

One of the Boys of Summer decided he wanted to run for governor and continue William Winter's legacy and vision. Ray Mabus did something I had never seen before. He put together a team that included the Deposit Guarantee board and the Trustmark Board, as well as the Millsaps board and the Ole Miss board. Losing seemed really damn unlikely.

He called his plan “Better Education for Success Tomorrow” or B.E.S.T. The year before his election, Mississippi amended the constitution to allow for gubernatorial succession. Mabus would be the first person to test it. In the Democratic primary, he ran against Wayne Dowdy, which was a problem for many of us because we’d have to split the baby as we’d previously supported both candidates.

Mabus won the primary, and ran against Kirk Fordice as the Republican. There had never been a Republican governor of Mississippi. A lot of people considered it impossible. Gil Carmichael had come as close as anybody, and the way things worked out, I wished to hell he’d won. You could fill out a baseball team with the names of guys who I thought would make a great first Republican Governor of Mississippi. Kirk Fordice wouldn’t have been on the team. I didn’t know Fordice that well, but I knew he ran with a pretty fast crowd. Interpret that however you want. His wife was a lady. I’ll always add that when I mention anything about Kirk Fordice.

One day, at an Ole Miss football game at Veterans Memorial Stadium in Jackson, the announcer said, “Please give a warm Mississippi Welcome to the Governor of Mississippi and the first lady!” and all the starched white oxford cloth shirts in the student section started to boo, really loudly. I was at the game with Daddy, Rowan Taylor, and Bob Fortenberry. I looked at Daddy and said, “Are we in trouble?” He didn’t answer.

Mississippi changed. Education was no longer at the top of the ticket; cutting taxes was. We were now part of the Republican Revolution started by Ronald Reagan. I have a lot of stories about Kirk Fordice that I won’t tell. You probably already know the one about Burt Case. It’s on YouTube. Like I said, Pat Fordice was a lady. She deserved better.

One day, Daddy was dictating a letter to Rowan Taylor, Charlie Deaton, Robert Wingate, Ross Bass, and Bob Fortenberry about a fishing trip where they would discuss their plan now that Mississippi had a Republican Governor, and he decided to die rather than finish it. Laying in his box, I was alone with him for a moment. I put my hand on top of his. “You can’t do this to me, Buddy. We’re not done yet. We’re not done yet, Goddamnit.”

Whatever work there was left to be done about pulling Mississippi off the bottom of every list would have to be done without Jim Campbell.

For a while, I thought maybe I could pull a Hamlet and kill everybody in sight, but I decided against it. I’d been talking about moving to Los Angeles. I wasn’t doing anybody any favors in the office supply business. I liked the people in that business, but I just felt like whatever I was was probably dying on the vine.

A woman I knew who knew more about me than most said, “John Grisham wasn’t much younger than you when he published his first book.”

“John Grisham went to Ole Miss,” I said, as if that settled something. It also wasn’t true. Grisham went to school all over Mississippi but graduated from that school with the cowbells. He went to law school at Ole Miss, though, and he adopted them as his own and built a ranch there where the writer in residence lives.

After struggling with the Hamlet plan for a while, I eventually noticed that Mississippi was still at the bottom of every list, and I wasn’t doing a goddamn thing about it. Eventually, I took my rest inside a crystal cavern, and a witch sealed me in for a decade. When I got out, I noticed that Mississippi was still at the bottom of every list, but I decided to try again.

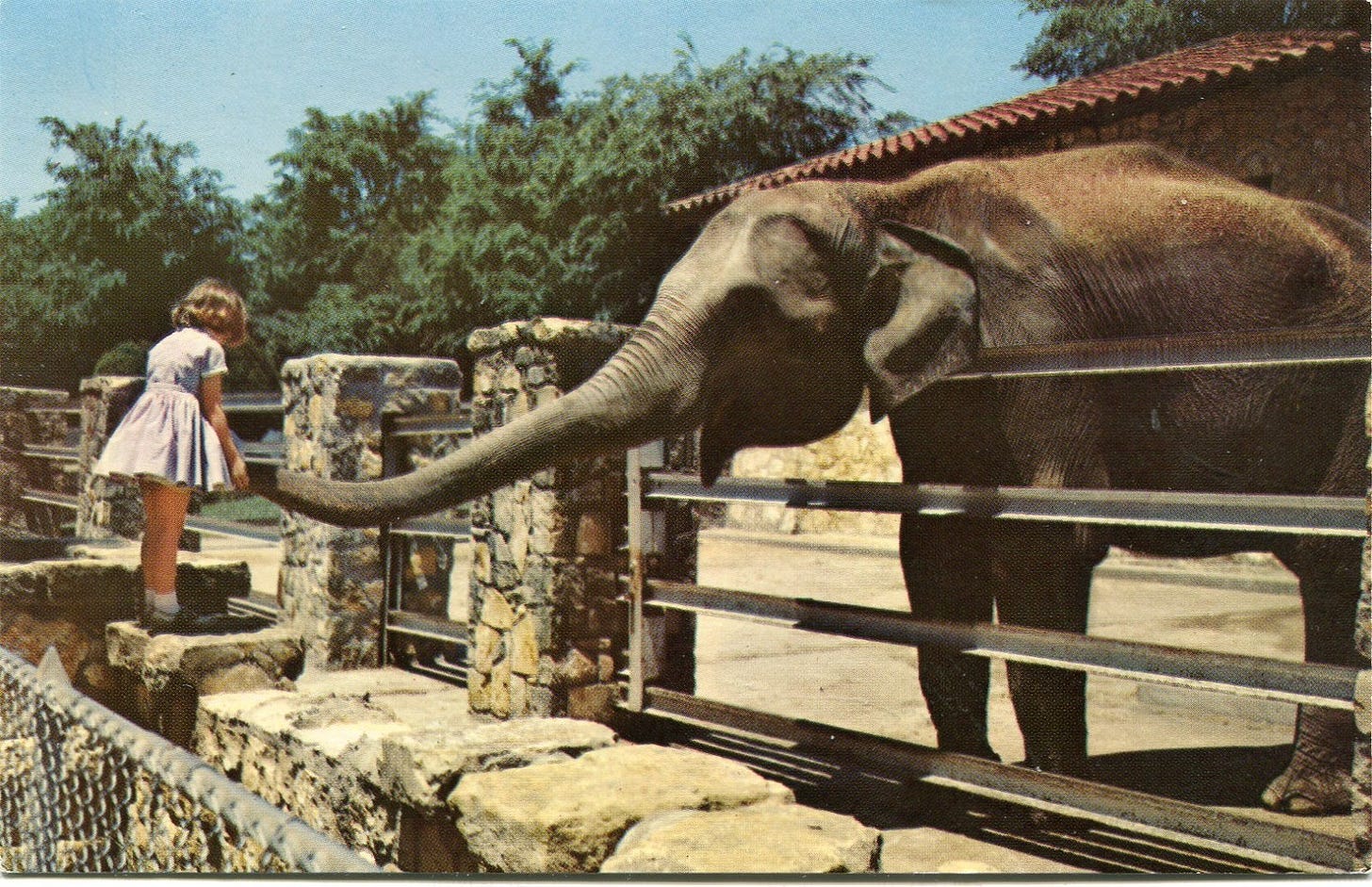

Oh, about the elephant. My grandfather had a joke. It goes like this: “How do you eat an Elephant?”

“I don’t know, Granddaddy, how DO you eat an elephant?”

“One bite at a time, Buddy. One bite at a time.”

That was supposed to make me laugh and motivate me. You’d be surprised how many times somebody in my family told me that story.

So, I’m looking at this gigantic dead elephant. It’s been cooked, I guess. All I can think of is, “you’re SUPPOSED to be here with me, goddamnit. I’m not supposed to do this without you. How am I supposed to EAT all this?”

One bite at a time, Buddy. One bite at a time.