Feist Dog woke up before I did. “It’s time to work, Boss.” Then, I felt his cold nose on my neck, forcing itself into my sleeping hand. Feist Dog is an imaginary character, in part, based on a very real old yellow cat I had once.

One night, very late, I was nursing a broken heart, so I went to Burger King, which stayed open until two o’clock in the morning in the marginal part of town. I heard a sound coming from the dumpster in line at the drive-through. Pulling into a parking space, I opened the lid enough to see what was inside. At the bottom of the dumpster were three dead kittens and one live one, but no garbage. Somebody had thrown out four perfectly good cats.

I originally thought not to name the cat since I wouldn’t keep it. After feeding him for a week with a dropper, this “not keeping him” business wasn’t working out. As he grew, I decided that I probably shouldn’t name him because cats don’t speak English. Then, he became “that dumpster cat.” That was his official designation, but not a name for a while. Three years later, the woman who became my wife noticed I mostly called him “buddy” because that’s what my father called me, and Buddy became his name.

Buddy was an aggressive and very moody cat. When he wanted attention, though, he could be very insistent. When I was at the computer, he would force the mouse out of my hand with his nose so that I had no choice but to rub his striped head. I would pull him into my lap for some good and true loving and apologize for what we did to his testicles. If he was going to live in the house, my wife insisted on it; at least, that’s what I told the cat.

When Feist Dog woke me, I was dreaming about the whales again. Creatures so vast that I couldn’t see their head and their tail at the same time. When I swam among them, I had no reason to breathe. Their presence replenished my body.

The whales have always been with me. I blame a Jacques Cousteau documentary on Singing Whales when I was seven for that. The whales are characters in one of my books. At the moment, I have three unfinished books. That’s probably why Feist Dog wakes me up just as the sun peaks its nose over the horizon. I have work to do.

One book is nearly complete, but I probably won’t seek to publish it. It’s nonfiction about the years and the people behind the rise of private schools in Jackson, Mississippi. I’m not a journalist, but I know the basics of how it’s done, and I’ve verified my sources. I’m convinced that what I’ve written reasonably accurately depicts what happened in those days. That’s the problem. It’s accurate.

If I ever have a really serious moral dilemma, I discuss it with my sister. Even though most of the central characters of the Academy book are dead, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren aren’t. That’s what stays my hand about ever publishing it. I might have the right to change someone’s opinion of their grandfather, but do I have the heart for it? She agrees.

I mentioned this in Sunday School, and one of my classmates reminded me there must be a reckoning of what people in Mississippi did in those days. I agree with her; I just don’t know if I’m that guy. I know guys who abandoned all else and sought justice for what Mississippi did in the sixties and seventies. There was a price to pay, far beyond just making a bunch of peckerwoods hate you. I’m eternally grateful that they did it; I just don’t know if I can do it for myself. Being in the community and being critical of the community can be a painful path.

The second book is about a monster story they told me as a child called “Rudy.” I really like the Rudy story, but I‘m determined to make it more than just a silly monster story, and that’s why it’s not finished. Maybe that’s a mistake. Maybe I should just let it be a silly story about a monster and let people enjoy it that way. Whatever the case, it sits unfinished.

I think the third book has the most potential. Tentatively titled “Summer’s End,” it begins with the premise that a viral disease makes it so that the old never die, the young never grow up, and everybody in between dies out, leaving the world filled with pairings of grandparents and grandchildren but nobody else—forever.

Colonies on Mars aren’t ever infected with the virus that hit Earth, so a portion of Mankind lives as it always has: born, growing, aging, and dying. However, they can never return to their home on Earth without the risk of infecting the population on Mars.

One thing that happens when the entire population of Earth is either young forever or old forever is that they begin to see things in a new light. One thing they discovered is that the cetaceans and cephalopods of the ocean were always our equal intellectually if not our superior, but their intelligence was so alien to ours that we had never noticed it before.

This is what became of watching all the Jacques Cousteau movies when I was a child. I’m very consciously trying not to borrow elements from “Startides Rising.” It’s impossible to escape influences from other stories, but I’d like for this one to be as original as I can make it.

If I live long enough, at least two of these stories will be books one day. I don’t know what will happen with the third. It’s been suggested that I turn it into fiction. That’s a possibility. I've already published my part of that story, at least things that happened directly to me, as essays. I can tell my story and not feel guilty. Telling someone else’s story is problematic for me.

I’m going to move from one part of this story to the next without a segue, hoping that at least some of you can figure out the connection between the two parts. If it doesn’t work, I apologize. Nearly all of my writing is experimental. Sometimes, I like to pull back the curtain and let people see the scaffolding of my writing.

I genuinely try to be a gentleman, but I think it’s time to admit I failed. If I were truly a gentleman, then, by now, I would have been married for forty years to the same person, and we’d both be happy. What actually happened is that there has been a string of far too many women in my life ever to consider myself a true gentleman. If anything, I’ve been a cad about women and a charlatan with regards to this gentleman business.

When men are together, they like to make bluff charges at each other as a test of their metal and yours. Among friends, the question “Who’re you fucking now?” is a challenge of one’s manliness. A gentleman reserves the right to deny the challenge, but the call must be answered. “Nobody” or “Nobody in particular” is my answer for most strata of men I know. If lying in the positive is permissible, then certainly lying in the negative is also permissible.

There are a few men with whom I feel a moral obligation to answer honestly. One is Doug Mann, another is Tom Lewis, and the third is my Brother-in-Law.

One day, at the Mississippi State Fair, my brother-in-law-who-shall-not-be-named saw a woman we both knew, but he recognized that I knew her considerably better. He remarked on the shape and volume of her bosom and asked if I had any more information about the subject. I answered honestly. My sister looked at us both like we were about to kill and eat a baby goat. So did her friends.

During the days when I was telling everyone I was on the eve of moving to Los Angeles permanently, I became socially entangled with a beautiful young Jewish woman who was a junior writer for a popular variety show on Fox. For many years, lithe creatures with obsidian eyes and black velvet hair have infested my dreams. For a while, I really thought she was “the one.” She wasn’t.

Most of her friends found my Southernness charming and amusing, although they generally assumed I was intellectually inferior to them. Maybe I was. One of her black friends called me “cuz” because we both used “y’all” in most sentences. He was one of the head writers for “In Living Color” and had a pretty remarkable career since.

Except for the times when I was around Forrest Ackerman and his friends, most of my adventures in Los Angeles felt like Quentin Compson in Cambridge from “The Sound and the Fury” and “Absalom, Absalom!”. Had I stayed there, I might have ended up like Quentin, filling my pockets with weights so I would sink when I jumped off the Santa Monica Pier.

Elizabeth’s black friend from “In Living Color” became my Deacon from “The Sound And The Fury.” Elizabeth’s not her real name, but it’s a biblical name, and I’d rather not use her real name. Had I stayed, my Los Angeles Deacon probably would have played a similar role to Quentin’s Deacon and I would have entrusted him with my final letter.

A second-generation Los Angelean and a third-generation American, Elizabeth had many Jewish friends with Eastern European heritage who lived in Los Angeles for at least two generations but worked to maintain their culture as it was before they came to this country.

Part of why Jews still exist is that they found ways to remain Jewish, no matter how many times somebody forced them off their land. I always rather admired that about them. My own people seemed only too happy to abandon their druid heritage when the Christian missionaries arrived in Scotland. It’s probably a good thing. Otherwise, we’d still be putting people inside men made of wicker and starting a fire. I have a list of names of potential sacrifices.

Elizabeth had two friends who were very gay and very Jewish. They found me amusing, like a pet with no hair. When I saw them, they always asked if I’d set off any bombs lately.

I was close to turning thirty years old when I met these men. When I was four years old, some peckerwoods put a bomb in the Beth Israel Synagogue in my home in Jackson, Mississippi, and made an effort to blow it off the map. It had been over twenty years since the bombing, but to people for whom terror had deep cultural intonations, my Mississippiness represented little more than just another potential terrorist. Of all the things they could know of me, that was first in their mind.

While I can’t say they were mean to me, they were very sure to draw noticeable distinctions between themselves and myself. One notable distinction they insisted on making was that they were both working writers, and I was not. I suppose it was ok for them to be friends with me so long as they held a superior position. Were our positions reversed, I can’t promise I would feel any differently. Being a gay ally helped, but not much.

Ultimately, Elizabeth decided that I wasn’t serious about writing, I wasn’t serious about Los Angeles, and I wasn’t serious about her. It was time for me to go. She was right, of course. She deserved better. She married a very wealthy older Iranian man a year or two later. A few years later, she divorced him and walked away with several million dollars in a community property settlement. With the money, she quit writing and went to law school. I lost track of her after that. I always wondered if her friends were kinder to her Iranian husband than they were to me.

When my Uncle Boyd was president of the US Chamber of Commerce, he traveled the country, where people wrote about his “Southern Charm” and “Old World Manners.” They actually wrote this in newspapers about a man from Mississippi. Although I never met him, I gathered that my Uncle was something of a self-promoter and used his position in the Chamber of Commerce to develop a small cult following for a while. Had he become a writer, he might have exploited that for the rest of his life. I’ve read his speeches. He was a better wordsmith than I, but he never saw any use in pursuing it.

My father was also a brilliant writer, but he would only write speeches and letters. He was absolutely against my writing as a vocation. As an avocation, I could do anything I wanted, including “this theater stuff,” but none of that was serious. Business was serious. In his heart, Daddy believed he was protecting me from myself. A boy who can’t read properly can’t write properly. He wasn’t wrong. The odds of my ever writing were astronomical. Something guided me through that briar hedge, though.

When it became my father’s turn to travel the country and speak on behalf of businesses in Mississippi, he received a very different reception than my uncle. When my father spoke, he wasn’t from the Mississippi of magnolia blossoms, hoop skirts, and old-world manners. Daddy was from the Mississippi of burning crosses, riots at Ole Miss, and dead Jewish boys buried in earthen dams in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Pictures of Emmett Till’s body and his mother, printed in Life Magazine, changed how the world saw Mississippi forever. Traveling Mississippians were no longer “southern gentlemen.” They were potential murderers.

Daddy’s response to all this was to embrace modernity in all its forms. Several of his peers did the same. A truly modern Mississippian was very different from the Ross Barnett version of Mississippi people saw on television and Life Magazine. He grew out his sideburns. He wore shoes with heels and suits with wide lapels that could double as ailerons.

In his career, Daddy ended up making decisions about the building of fifteen or twenty structures in Mississippi, including our family home. All of them featured very “modern” architectural styles. Think of the Ford Academic Complex at Millsaps or the main building at St. Dominics. These buildings, he believed, portrayed a new image of Mississippi, one very different from the one you saw in Life Magazine.

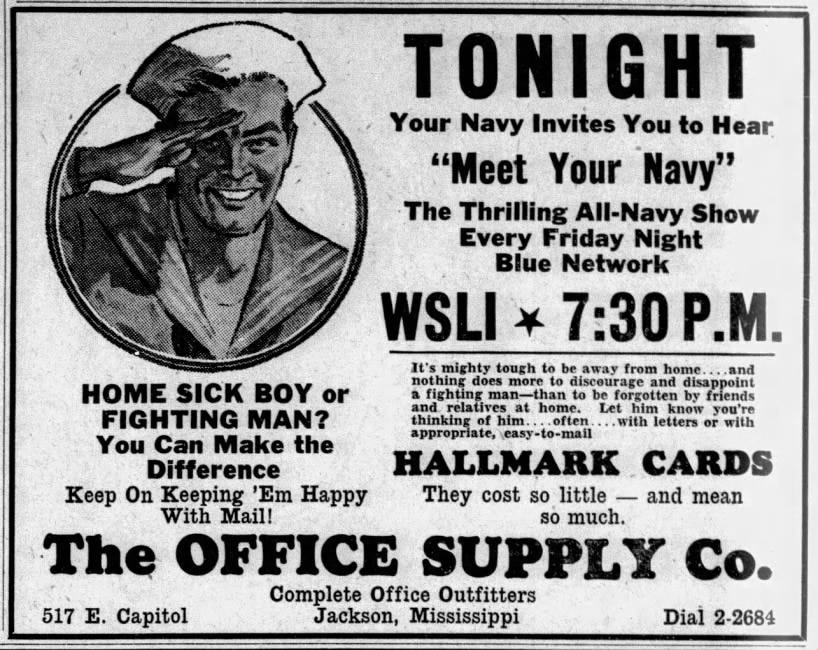

For fifty years, the slogan of the commercial division of our family business was “The Complete Office Outfitters.” For a while, Daddy changed it to “The Modern Office Outfitters” to reflect his effort to redefine what a Mississippi company meant.

One day, I found a set of blueprints among my mother’s many cupboards. The interior, I could tell, was our house, but the exterior looked like the house in The Brady Bunch, with an asymmetrical roofline and plate-glass windows. My father asked Fred Craig to design him a very modern-looking home. My mother told me that she and my Grandmother convinced him that, since it was to be a home, the facade should look “more normal,” and the street-side face of the house was re-designed. Even the bosses have bosses.

For a while, most of the men Daddy knew were involved in this business of rebranding Mississippi as something “modern.” For a while, it worked. We became known as “The Bold New City” and, for a while, became known for very moderate politics. This continued for a while. For a while, it seemed unstoppable, but then it did. A while, it seems, is a very fragile thing.

I don’t know if we lost our drive to be seen as something new, or if we never really changed at heart, but the drive to present the world with a “Bold New Mississippi” was over. More and more, we’re becoming again the Mississippi of the fifties and sixties. Some are diving back into it with relish. Some are not.

Were I to date Jewish girls from LA now, I would probably have to endure passive-aggressive asides from her friends about whether or not I was in “the goon squad” and whether my friends were using federal money meant for the poor to build volleyball courts for rich white girls.

I put away the idea of living in Los Angeles long ago. As much as I love its history, its people, and its architecture, I don’t belong there. I belong here. I don’t know how to change how the world sees us. Maybe we have to make some changes first.

Once my husband got us a kitten from Farmer Jim Neal, who advertised pets on his radio show. Unfortunately, my husband was a "dog person" so he didn't know that a tiny kitten with eyes not yet opened was too young to be adopted. But we fed her with an eye dropper for two long weeks and gave her a name. Maude grew up to be a fine cat and became a favorite in our Belhaven neighborhood where people fed her canned tuna as she visited up and down the street. Fortunately, she still came home to see us, probably because she liked our dog.

Boyd, if you are going to talk about your feist dog please be aware that many of your readers will remember Farmer Jim Neal who was on Jackson radio for 40+ years and always talked of his feist dog and in fact took guidance from him and shared that on air with his listeners. I respecfuly suggest you consider acknowledging Farmer Jim in order to give credit where it is due. If you have done so in a previous piece, my apologies.