Audio Version Below

It turns out that my grandmother was a great supporter and follower of the arts. She was always sure to point out to me who the artists, writers, and musicians were in Jackson. Incongruently, she was also adamant that the only reasonable thing for me would be to go into the family business, not art or writing. I always took that as her evaluation of my artistic and writing abilities.

She was right; of course, guys would always tell me how much they envied the opportunities hanging around my father brought me. Jumping on that gravy train and riding it as far as it went should have made me deliriously happy and successful. It didn’t.

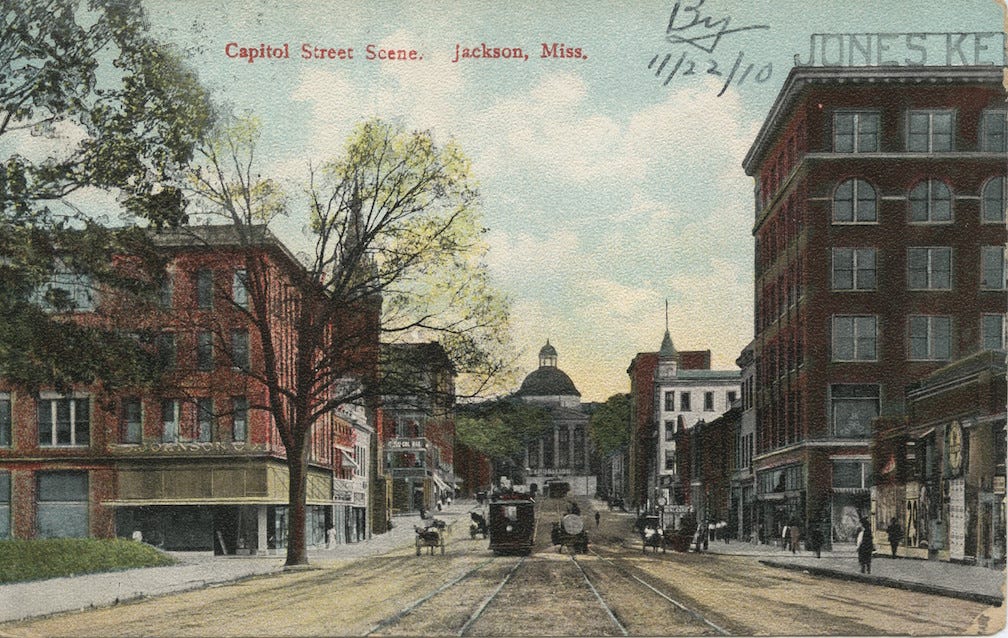

One afternoon, when I was eighteen or nineteen, I dropped some boxes my grandfather wanted at my grandmother’s house on St. Ann Street in Belhaven. When I got there, she was entertaining some ladies for coffee. One of them was Eudora Welty. When my grandmother said, I was going into the family business. Miss Welty told how, as a young woman, she would take the street car down to Capitol Street and buy typing paper and legal pads at the Office Supply Company.

Learning that there was this faint and frail connection between her work and my life was thrilling, but not in a way that I could tell anyone. If anyone reads this, it will be the first time anyone who wasn’t there that day ever hears the story.

Although I replayed that moment over and over in my mind for weeks, it was a lonely feeling to know I had no one to share it with. As far as anyone knew, I might have drawn some in Junior High School, but it was nothing serious. Besides, I was working full-time and going to college by then.

Being a writer was impossible for me because, even though I’d made great improvements, being a reader was still basically impossible. Even today, there’s a fair amount of tension and discomfort that comes with reading. I’ve tricked my dyslexia by learning techniques to work around it, but then I still have to struggle with ADHD, which wants me to focus on anything in the world besides my book.

Even now, there are times when I really want to read, but I can’t bring myself to do it. Even though I’ve been facing that tension for fifty-five years, it’s become something I still struggle with.

Memories of my mother include a cigarette, a scotch and tab in a stadium cup, and a book. That’s how she spent her evenings. My mother could easily consume two or three paperback books a week. The books, as I recall, were absolute crap, the paperback equivalent of “Murder She Wrote,” but they were still books, at that put her ahead of me.

Part of being a mother includes a fair amount of time waiting: waiting while the child is at the pediatrician, waiting while the child tries on new clothes, and waiting for the child to get out of class. My mother filled those spaces of time very casually reading. For me, it was like someone eating chocolate bars in front of a starving orphan. What I wouldn’t give to do what she did without thinking.

My mother would tell the story about how, when she was in high school, Kennington’s had a Santa Claus you could have your photograph taken with. When she sat down to have her photo taken, Santa asked her if she wanted to go to the movies. Noticing that one of Santa’s eyes didn’t follow the other one, she immediately knew it was her classmate Stuart Irby making a little Christmas money dressed as Santa.

Like my father, Mr. Irby was the second generation of a prominent Jackson business. Where the Irby Company met a windfall rebuilding the power grid in the UK after World War II, Mississippi School Supply met a windfall when returning soldiers had an unprecedented number of children. The baby boom boosted us enough to go from a local company to a regional one.

Not long after my father died and his company was broken up and sold off, Mr Irby also broke up and sold off his father’s company. Going from a second-generation company to a third-generation company is very difficult, sometimes impossible. With changes to the anti-trust laws brought on by the Reagan Administration, third-generation companies became very rare indeed.

Going into gentlemanly retirement, Mr. Irby procured office space on Capitol Street and began buying up all the surrounding property he could, including The Office Supply Company, which had been vacant since we moved the operation out to our main facility on Industrial Blvd. in West Jackson.

After my father died, I started to have very real trouble finding my way in life. I’d given up on everything I thought I wanted to follow him, and then he was gone. Mr. Irby took an interest in me and would sometimes invite me downtown to meet with him at his new office, across the street from what had been the Kennington Department Store.

No longer burdened with running the electrical supply company, he had all sorts of ideas about how to redevelop downtown Jackson, and he invited me to hear what he had in mind. One idea he was keen on was to turn the Office Supply Company building into a movie theater. He was concerned that modern movies were dark and depressing, and he wanted a movie theater that showed only uplifting and positive movies. He even suggested that it didn’t have to make much profit if I were willing to run it.

By then, I had tried a couple of times to buy the Capri Theater but gave it up because of the asbestos in the ceiling that was falling in. You could see sunlight through the roof of the Capri.

Being very familiar with the Office Supply building, I raised my objections to his plan. People are accustomed to convenient parking, I explained. While there is parking in the rear of the Office Supply Company, there are only three or four spaces in front. The only way to resolve that would be to make the rear entrance the front entrance.

We discussed ways to resolve and circumvent the parking issue. His active and creative mind made it interesting to see him plan his work. Besides the parking problem, I suggested that there was another insurmountable problem with his plan. Inside the Office Supply Company, running down the middle of the building, were four steel columns supporting the roof. I knew enough about theaters to know that you can’t have four columns in the middle of your proscenium.

Mr Irby’s youngest child was my age. His oldest child was a year older than my wife, who was almost six years older than me. She didn’t care for young Stuart. Apparently, he had been rude to her when they were at Murrah. I didn’t know my wife in high school, but I’ve seen photographs. She was catch-your-attention-from-across-the-room attractive. If he was rude to her, I suspect he was trying to get her attention.

Young Stuart loved music, art, and film. His mother encouraged it. As Mrs. Irby descended deeper and deeper into Alzheimer’s, Mr. Irby prepared a space for her in his office building where she could dance and play the piano as she wished. Her abilies with music stayed with her much longer than the rest of her memories.

With an unchristian amount of money at his disposal and no enterprise to take up his time, young Stuart began drinking considerably and spending every night playing piano and drinking himself senseless at the Jackson Country Club.

At about the same time, I was spending an equal amount of time drinking an equal amount, but at public drinking places like Scrooges and M and M’s in Banner Hall. As several people pointed out, privilege oozed from my pores. I hated it. I wanted to be a man of the people despite who my father and my uncle were. The Country Club was the last place I wanted to be.

For a while, the tax code was such that your job could pay for memberships at places like the Jackson Country Club or the University Club, which would be counted as an expense. The law eventually changed and that became taxable income, but for a while, being offered membership to the CCJ by your work was a sign that you were destined to be somebody.

My father asked if I wanted a junior membership at the Country Club of Jackson. The company would pay for it, but I would pay my bar tab. I told him that I knew a lot of guys for whom membership at the Country Club meant that they made it in the world and were somebody to be respected. If I accepted his offer, it wouldn’t mean that I had made it in the world; it would mean that my father had made it in the world, which wasn’t the same thing.

I thanked him for the offer, but if I took it, people would think I was a snob more than they already did. I tried to make him laugh by saying I rarely played golf and having another place to drink probably wouldn’t benefit me. He said he understood and respected my sensitivity to whether or not people thought I was a snob.

I took the opportunity to ask if he had a chance to look at my proposal yet. I was not very good at my job and didn’t have much to offer by way of selling office supplies, but when AOL bought Compuserve, I had an idea that Mississippi School Supply Company, and especially The Office Supply Company, could market their wares in a new way using computers connected to each other. Maybe this could fit in with his idea to develop direct-market catalogs.

Six years before the Mosaic web browser and Amazon.com, my idea of selling things “online” seemed like a long shot, but Daddy said I could try. Predictably, interest in the market was very, very slow in the first few years. Nobody had ever bought anything “online” before. When Daddy died, one of the first things the new CEO did was cut Missco's online division. Once Amazon became one of the world’s largest companies, I wanted to ask him about his decision to cut us out of a market where we were pioneers, but I figured that’d be sour grapes. I didn’t care for the guy, but rubbing his nose in it, I figured it was beneath me.

One night, young Stuart Irby was drinking at the Country Club, playing the piano and singing and being the life of the party. Too drunk to drive home, he had his wife drive. A fight broke out, and in the ruckus, their speeding car crossed the line and struck the oncoming car driven by a young doctor and his wife. The young doctor and his wife were burned to death in their car.

The trial and the publicity surrounding this consumed Jackson for a while. I had a great deal of sympathy for Stuart and Karen and wrote several essays and letters in support of them, but, in the end, she was found guilty, and Stuart took his own life.

When my wife told me what happened to Stuart, all I could think was that he loved music. He would still be alive and happy if he had been encouraged to pursue his music rather than trying to force him into this third-generation businessman model.

They say that trying to be a Ford is what killed Edsel Ford. I think trying to be an Irby is what killed young Stuart. From a very young age, I knew that fate lay ahead of me, like a tiger in the dark if I let it. Had my father lived, I probably would have died like Stuart did, or at least died from my alcoholism. I almost did, anyway.

I’m still working on this “man of the people” thing. Recognizing the privilege I was born into was an important first step. The Country Club is still filled with guys who are very anxious to prove they made it in life, and because they made it, they’re better than the people who work there. Some guys didn’t really do anything to earn their membership but still consider themselves better than the people who work there.

The guys who “make it” in life are the ones who make the most of the gifts God gives them, not the ones who make the most of the money their parents left them. It took me a long time to figure out that I not only could do that but that I needed to do it. There actually were gifts God gave me, even though my family seemed against the idea.

Eudora Welty bought typing paper at my Uncle’s store. That idea, that seed, small as it is, grew inside me for forty years. Clearly, I’ll never do what she did, but I can now do what I was meant to do, and that means something. I wish Stuart had ever been able to find that kind of peace.

Beautiful piece, Boyd. It rings true to the last word.