Fried Pies, Mustard Gas, The Help, and Pillars of Salt

I had advance notice that “The Help” was coming out, and its subject matter. I asked the Lesbian at Lemuria Book Store to hold me a copy when they came in. I’ve always gotten along with lesbians. We have similar musical tastes and political perspectives. By 2009, I was beginning to shut down, but my twilight bark network was still fully functional.

A quick read, my first thought was that she would get some shit for what she was saying, even though it was the truth, her truth and my truth. Going into the twenty-first century, I didn’t know how people were going to react to a story about a basic white girl’s mom’s generation and racism in Mississippi. In the end, two of the women who starred in the film denounced it and her.

Kathryn Stockett actually isn’t a basic white girl. Six years younger than me, she was part of the fabric of Mississippi before she ever left here for some elephant school to learn writing.

When I was younger, Kathryn’s grandfather would call me sometimes to ask if I still wanted to board a horse he knew I didn’t have. What he wanted was to discuss old times and old political alliances. The number of people who remembered him as one of the most influential political leaders (even though he never held office) was dwindling. Even though my knowledge was second and third hand, I knew all the stories.

There was an old farmhouse at Stockett Stables, at the end of Pearl Street, the last stop between Jackson, the Pearl River, and civilized Mississippi. You hear a lot about cigars and political back rooms. Mississippi had chewing tobacco and a screened-in porch. There, deals were brokered, good or bad, that guided the Mississippi Legislature.

Warren Hood learned to drive a surrey back home. On Sundays, and some Saturdays, he and Robert Stockett would race surries through the sabbath-empty streets of downtown. With Neshoba County Fair coming up, you can still see Surrey Races, but don’t expect to see any older white men driving them. It’s actually quite thrilling.

Even though it’s fictional, every word in “The Help” is true. I laughed when they cast Leslie Jordan to play the fictional version of my Uncle Tom, the editor of the paper. He wouldn’t have. At least not as long as he was alive. Maybe being dead for forty years has softened him.

Ultimately, the question becomes, “How can you say you love someone, and keep them in a sort of extended slavery?” The novel deals with this directly, but provides no answer.

The strollers they have for kids these days might be Autobots. They’re not robots in disguise. They’re just robots. I don’t think they had a stroller for me. My mom had two previous siblings, a Nanny and a Hattie.

In the parlance of Learned Mississippi, a “nanny” isn’t an English babysitter hired to impress the neighbors. A “Nanny” is a mother or grandmother. Nanny was my grandmother and my mother’s mom. Nanny’s mother was also called Nanny. I think it’s a title of some sort that’s only viable in rural Hinds County.

Hattie was Hattie, my best and often only friend. We watched Dr. Smiff and dat robot together, and Gotziller movies. In terms of “The Help,” she was my Abeline, my Constantine, and my Minny. She was also from rural Hinds County, in Utica. The more espresso parts.

A reckless child, I’ve written before about how many times Hattie saved my life. She wore a pale blue uniform and had arms like great Swiss chocolate anacondas. Once I found my way to them, I knew I was safe. There are those who will judge me for keeping an African house servant into the twentieth century, but it wasn’t really my choice, and she was often my only friend.

When the baby princess was born, mother got, or was given, a fine black stroller with a hood for the sun. It went bouncy, bouncy, which was almost as entertaining as having a baby, plus it made the baby laugh. Hattie, the princess and I would prominade up and down our Northside Drive neighborhood.

Hattie lived on Rose Street, near Jackson State and Poindexter Park. It had once been a larger white home, but it was now the base for the Grant family. One night, now in our new near Eastover home, the phone rang late. Mother took it, but then Daddy took it.

Since I wouldn’t leave him alone, Daddy had me ride in the passenger side of his Oldsmobile Toronado. At UMMC, I learned that Hattie’s older boy had been shot, confused for another man. I stayed in the car while Daddy conferred with Chief Black. The hospital was big and modern and alien. I was worried about John-Roy. He would limp the rest of his life, but he was ok.

I was born at pretty much the precise moment where segregation had produced the head of a boil that had to be lanced in Mississippi. Medgar Evers was shot. A few days later, less than a mile away, I was born. The game was on then.

The plan was for me to be baptized by Rev. Selah, who had been the head pastor at Galloway United Methodist Church since before Moses built the church, before Ulysses was born. That didn’t happen.

The question of whether or not to integrate Galloway’s ancient pews was part of the swelling boil. Rev. Selah felt one way, and the men guarding the door felt another. Rev. Selah resigned his post from the pulpit while I was home with Nanny. I would be baptized by Rev. Cunningham, who also found the situation at Galloway so untenable that he wanted to leave as well. And then he wrote a book about it.

Pretty soon, the full-on schism of the Methodist Church began. Galloway stayed true and worked out their problems, even though enough people left to make their own church. My grandfather’s church in Hesterville, Mississippi, became an independent Methodist church. It broke his heart.

Every summer, we made the trip from Jackson to Hesterville for the Bethel Church homecoming. Having a big event like that in August in Mississippi seems like a pretty silly thing to do. The older folks didn’t mind it so much. It reminded them of home, I guess.

Like most church homecomings, we served dinner on the grounds. Everybody did their part. My grandfather picked up two buckets of Kentucky Chicken and a cooler full of co-colas and cold drinks. My mother was the queen of hors d'oeuvres in Jackson. She brought little baby quiche Lorraines and sausage toast points. Aunt Annie, Cousin Robert’s mom, was the most famous cook in the bunch. She made fried pies and corn relish. When Clan Campbell still lived in Hesterville (actually out from Hesterville in Possumneck), they raised corn and beans to survive.

Robert Wingate’s wife, Libba, made deviled eggs and ambrosia. Her hair was sculptural, and she spoke in a way that I associated with the Mississippi Delta until the end of time. Robert was her second attempt at the husband thing. A quiet family scandal. Husband number one vanished in what I was sure was some sort of Southern Gothic mystery, but was most likely just him moving to Memphis.

The only preachers I ever really knew were Clay Lee and Bill Gober. Clay spoke like a friendly professor and discussed the more gentile aspects of what Jesus wanted from us. Bill Gober mainly delivered forgettable sermons until he decided to sing.

As the momentum for the Independent Methodist movement wore thin, finding Independent Methodist preachers became a challenge. Hesterville only had an actual preacher once a month. Independent Methodists returned to actual circuits.

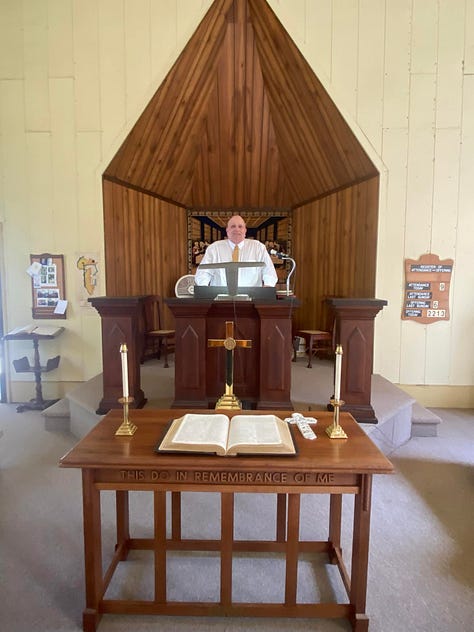

Bethel Church had a recessed pulpit, which is apparantly architecturally significant among country churches. There was no air conditioning, but plenty of funeral home fans. I see from more recent photos that they’ve installed a window unit.

From our famous recessed pulpit, this man, missing about three teeth, spoke about lakes of fire, pillars of salt and fire, and the risks one takes by not repenting and asking Jesus into our heart. I was pretty sure he was speaking to us, Jackson folks, directly. We were a pretty sinful lot, spending so much time with the legislators and being so near to the fabled Gold Coast of Rankin County.

Starting about ten till noon, Robert Wingate and my Grandfather would start looking at their watches very noticeably. My father would wake up and begin adjusting his weight. Talking about Jesus invariably made him sleepy. Ruddy-faced and thin, Robert Wingate was not at all above walking out of a church service run over too late. As he began putting on his seersucker coat, the circuit rider got the message.

Opening all the containers of fried pies, chicken, and caramel cakes, I would examine the other homecomers, trying to figure out who was blood kin and who were part of the Snopes family. There’s no one named Snopes in the long annals of Mississippi, but thanks to Faulkner, everybody knew the word.

After having our fill of chicken, devilled eggs, and fried pies, it was time to visit the dead. The Campbell Clan took up an entire row toward the back. My Uncle Boyd bought a fancy marble tombstone for his mother. Knowing his time was coming, he ordered a matching one for himself and his brother Robert.

Robert was the most storied of all the Campbells. A childhood infection left him with one leg shorter than the other. His father, “Big Cap,” who only had one arm himself, made a small wagon and trained a dog to pull Robert to school. Cap believed the only way out of Mississippi poverty was through education. An idea that’s now carried on to the fourth generation.

Robert became a lawyer back in the day when all you had to do was take classes at some school in Oxford. Everybody else got their sheepskin at a more sensible place, like Millsaps College.

Hanging out his sheepskin in the major town of Kosciusko, Robert’s law career was cut short when America went to war with the German Kaiser. When the war crossed the border into France, Robert tried to enlist.

Like Hemingway, who became an ambulance driver after he was rejected as a soldier due to his eyesight, Robert Campbell was rejected as a soldier because of his short leg. Hemingway survived the war and went on to invent the Bloody Mary in Paris. Returning from the trenches at twilight, with an ambulance filled with wounded, Robert couldn’t see the mustard gas pooling up in a low spot in the road. By the time he made it to camp, Robert was coughing up blood, and his passengers were dead.

Buried in France because returning tens of thousands of American bodies by ship was unthinkable, Robert would have a tombstone but no tomb in Hesterville, Mississippi. Knowing his end was coming, Boyd Campbell ordered stones for himself and his brother with orders to finish carving out his death date when he crossed over. There they sit today, next to their mother and cap, who was buried without his arm.

With segregation, the issue became “Justice delayed is justice denied.” Most Mississippi Methodists wanted to do right by their colored brethren; they just didn’t want to rock the boat. Well, some wanted to, and they did.

In Hesterville, the African congregation didn’t yet have the money for their own church. Old Cap had a steam-powered saw mill. He would sell them lumber on payments, but in the meantime, they could use the Bethel Methodist church in the evenings when the white congregation went home. Nobody thought much of it.

At Bethel, the colored graveyard sat at a perpendicular angle to the church from the white graveyard. The tombstones were often homemade. Sometimes concrete. One poor soul had his mortal remains marked by a remarkably large corprolite. A corprolite is fossilized dinosaur poop. I always imagined an angry wife made the choice of the tombstone.

The Methodist Church is now totally integrated, although most congregations remain mostly white or mostly black. As congregations are usually built around family connections, it will take several more generations for that to change. The Bishop is a black woman who everyone seems to love.

For the most part, there are few remnants of the sixties schism in the Methodist Church. Bethel still says they’re independent Methodists. I have no idea where they get preachers. The church split again, this time over issues of gender and sexuality. I suppose that’s our fate.

I haven’t been back to the Bethel Church in ages. It’s nothing but ghosts for me now. It’s well-kept up from what I can tell. I can’t tell you the last time I saw somebody serving fried fruit pies in Mississippi. Aunt Annie died among the zinnias and gardenias in her yard. That’s about the best way possible.