One day soon, on some sunny Sunday, my church will baptize the first member of its ninth generation. Stretching from the nineteenth century, before slavery, through the Civil War, through the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, that’s a lot of connectivity, a lot of family, a lot of community, a lot of Mississippi lives.

We had our Halloween celebration last night. Now, they do a thing called “Trunk-or-Treat,” which is a concentrated form of Trick-or-Treat. You line up many cars in a parking lot, decorate the trunks, and let the tiny goblins go from car to car, collecting candy. Parents get to pick out the peanut butter cups and bite-sized Milky Way dark bars. Methodists, at least United Methodists, tend not to freak out about Halloween. It might be because most of us came from the Irish and Scottish cultures from which Halloween was borrowed. We also tend not to freak out about much unless the service goes ten minutes over. That’ll cause a commotion.

Sitting across from our ancient facade, under the watchful eyes of the giant gold eagle perched on the New Capitol dome, I started feeling nostalgic for people who aren’t alive anymore and started telling my friends about my life as a young man.

I usually try not to do that. My life from twenty to thirty-five was pretty different from normal people. I’m aware that a lot of my stories sound like bullshit. They also sound like I’m especially pleased with myself and want them to be, too. That’s the part I can’t stand. Humility is one of the most important traits to me. It comes naturally because I can’t ever point to a moment in my life where I felt like I did enough, that what I contributed was sufficient, and whenever the world around me strains or suffers, I will always feel like I could have stopped it.

My father felt the same way. My father became very politically active, not because it made him powerful (because it didn’t) but because he saw that as a way to do the most for the people around him. His father felt the same way, and so did his uncle and his grandfather. Campbell men probably felt like this on the boat over from Scottland.

He didn’t hesitate to endorse my efforts to become politically involved. He suggested that I take a book he gave me and memorize the names and committee assignments for everybody in the Mississippi House of Representatives and Senate. I don’t think he expected I would ever actually do it, but I did.

My father and I usually supported the same person for Governor of Mississippi, but not always. I used to tell him we were tied when it came to wins and losses, but only because two of his candidates lost to Cliff Finch in the same election.

My father died in his office. It took about seven minutes. I was there the moment the life left his body. The EMTs continued efforts to resuscitate him on the way to the hospital, but I knew he was gone. I saw him leave.

The moment before he died, he was dictating a letter to Robert Wingate, Rowan Taylor, Dr. Ross Bass, Bob Fortenberry, and Charlie Deaton. This was his crew. They’d been involved in Mississippi politics since Ross Barnett. They ran Deaton for governor three times and William Winter four. I think that fourth race is why Winter got the job, but Deaton never did.

The letter's purpose was to organize a fishing trip. My father never learned to type, even though he made sure I did, so his secretary took dictation. The purpose of the fishing trip, besides the drinking and the fishing, was to discuss their way forward now that Mississippi had its first Republican Governor in the one hundred and forty years since the Civil War. Mississippi had been toying with the idea of being a two-party state for almost twenty years. They weren’t against the idea. Their group had thrown their lot in with three Republican candidates for Mississippi Governor, just not the one who won.

When he died, even though he and I had been talking about my leaving for California for almost three years, I was still deeply engaged in Mississippi. I was on four civic boards and had my fingers in as many pies as I could find, even though I felt like I was dying on the inside. Throwing in with whoever or wherever I felt like they needed help was my way of coping with the poverty and desperation that exists in Mississippi. It’s called “survivor’s guilt.” It’s part of my DNA.

The next fifteen years were remarkably difficult. It started with me falling off a ladder and breaking my leg. Then Lance Goss spent almost four years dying. That’s when things really started to heat up. Nine-eleven happened. Someone I cared about lived in Manhattan and was pretty vulnerable in her ninth decade. I couldn’t reach her by phone for days. Then, the war in Afghanistan, then Iraq. Katrina, health problems, a protracted divorce, and more deaths. Millsaps and the city of Jackson were visibly beginning to take on water. Jackson spent over a year unable to get anybody to take the job of Chief of Police.

By 2008, I felt like whatever contributions I had made to the world, whatever my involvement in the world brought, might have to be enough because my batteries were drained and my sails were tattered. In five years, I’d move into a tower downtown and lock myself away, waiting to die.

I had seen Barack Obama's speech at the Democratic National Convention four years before. I’d heard he would probably make a run at the nomination. Other black men had run for president but did it to make a point, not win. People were saying this guy could win. I wasn’t so sure.

Living in Mississippi, I was very aware of what even the thought of a black president would do to some people—quite a lot of people, actually. Other than talking about Socialized Medicine, which Democrats had been talking about since Johnson, what this Obama guy was saying seemed pretty moderate to me. Were he white, I wouldn’t have had a single reservation.

Even though we elected a few young guys and one Irish Catholic, every president before 2008 looked like they could be brothers. When Kennedy was elected president, there were still people who called the Irish “Broom-pushers,” but it’d been a couple of generations since that was true. This young, half-black Hawaiian with a gold-key education and a Muslim name had the power to upset the apple cart just by existing.

We’d been in a proxy war with the Muslim world since the sixties, and in 2008, we were in a live shooting war. “It’s a good thing I retired from politics,” I thought because whatever happened next was going to get crazy, I thought.

It did get crazy. They started saying that Obama was born in Kenya. His wife was a man in a dress (I never knew how they explained the two kids). He was a communist, a sleeper agent for the Soviets (who no longer existed), and the Muslim world. A wrestling promoter and failed casino operator from New York pushed the “born in Kenya” idea harder than anybody. Everybody I knew in New York said he was a clown. He sure looked like one.

When Obama did finally produce his certificate of live birth from Hawaii, just as he said, the wrestling promoter and failed casino operator had a mental health moment. They say that when Obama made fun of him at the Washington Press dinner, the failed casino operator made the decision that it was time for him to run for president himself.

With the interest of a dispassionate outsider, I was fascinated by the campaign Obama ran. I knew people who were openly saying that if Obama won, he’d be assassinated in weeks. They weren’t saying they would do it, but they were sure somebody would. Based on how people were acting, I wondered if it might be true.

Obama is said to have been the first presidential candidate to fully utilize the Internet to raise money and gain support. Even before the election, people were writing articles about it. That he was doing well was undeniable.

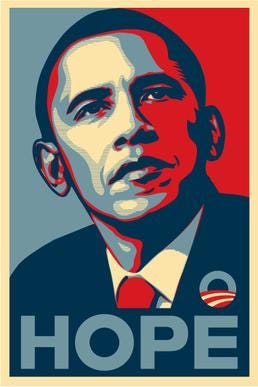

The now iconic Obama poster had his face in four colors and a single word, “HOPE.”

As a painter, I was interested in the poster. It looked like a block print, even though it was designed on the computer. As a writer, I was interested in the slogan—HOPE.

The entire slogan, as articulated in four or five key speeches, was “Hope Replaces Fear.”

At this point, I was supporting John McCain. He was the co-author of the McCain-Feingold Campaign Finance Reform Act in 2002. Rush Limbaugh and some of the other tea-party Republicans ripped him apart for it. I thought it was one of the most important pieces of legislation in my lifetime. I began to think that if Obama won, it’d be because McCain’s own party turned on him.

When Obama used the phrase “Hope Replaces Fear,” I don’t think he meant John McCain. I don’t think McCain believed it, either. At a campaign rally, a Republican Supporter told McCain that he was afraid of Obama because, as a Muslim (which Obama wasn’t), he was afraid that Obama would enable domestic terrorism. John McCain, the Republican candidate for president in a tight race, told his supporters that they didn’t have to be afraid of Obama because he was not a terrorist and he was a decent person. McCain’s own people booed him.

Had I been an undecided voter before, that moment would have made me a McCain man. I made the decision not to be involved in politics anymore, but that moment energized me.

When Obama won, I was afraid—not because of him but because of the people who said he would never live to take the oath of office. An Irish band, Hardy Drew and the Nancy Boys released a song called “There’s Nobody More Irish than Barack Obama.”

O'Leary, O'Reilly, O'Hare and O'Hara

There's no one as Irish as Barack O'Bama

From the old Blarney Stone to the green Hill of Tara

There's no one as Irish as Barack O'Bama

You don't believe it, I hear you say

Barack's as Irish as was JFK

His granddaddy’s daddy came from Moneygall

A small Irish village, known to you all.

He’s as Irish as bacon and cabbage and stew

He’s Hawaiian, Kenyan, American too

If he succeeds, and he has a chance

I’m sure our Barack will do Riverdance

From Kerry and Cork to old Donegal

Let’s hear it for Barack, from old Moneygall

From the Lakes of Killarney to old Connemara

There’s no one as Irish as Barack O’Bama

The song began to make me feel better. Hope was replacing fear.

In four years, it seemed unlikely that anyone or anything could stop Obama. I voted, but I didn’t get involved. I was already pretty deep in the cave of my own making.

I’ll probably never feel like I’ve done enough or was good enough. That’s just not in the cards. It’s also true. The world is far too broken for me to ever mend it. That produces quite a lot of fear, and fear is what made me give up on the world. Fear that I’d fail the things I loved. Fail the people I loved.

Hope replaces fear. I’ll never go back into that cave. I’ll never withdraw again. I learned a lesson from an Irish, African fella from Hawaii, not Kenya. HOPE.

Well said