Identity and Writers

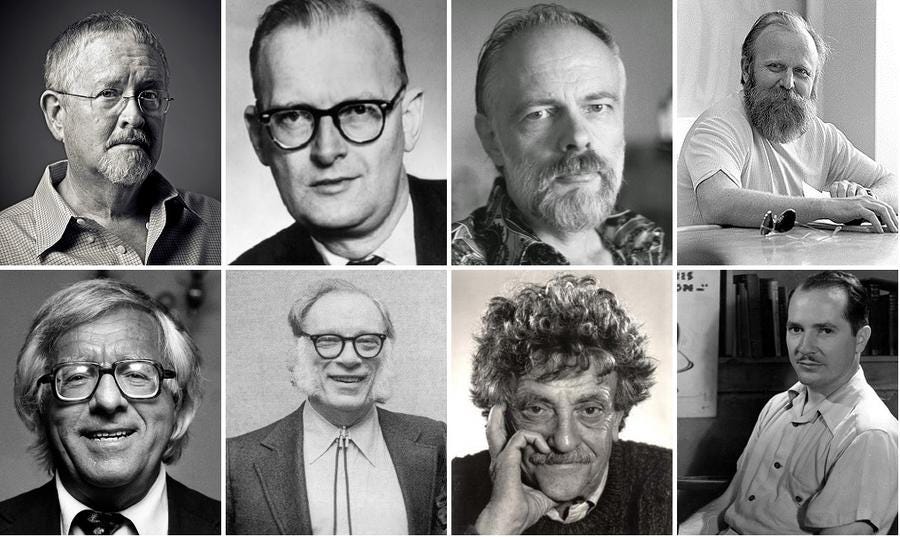

I started thinking about identity and writers because I wrote about science fiction writers. As I often do, I started by making a list. If I’m going to write about great science fiction writers, who do I mean? So, I made a list. After working with the list for a few hours, it dawned on me that nearly everyone on the list was a white male born between 1920 and 1970. I hadn’t intentionally left anyone out, but the trend was too clear to be natural, so I checked lists other people made about great science fiction writers, and their lists looked like mine.

I’ve studied “Mississippi Writers” from several different people, several different brilliant people, I should add. They all discuss “place” in writing, which is important, and if you put a gun to my head and made me teach about Mississippi Writers, I’d talk about it too, but soon after that, it became a matter of white men writers, white women writers, black men writers, black women writers, and in one instance, queer Mississippi writers, which is a pretty big body of work nobody ever talks about.

The thinking becomes, if you’re Richard Wright, and you’re writing when Richard Wright was writing. If you’re black like Richard Wright, his writing becomes part of the history of his subculture, which is an ancient and vital part of writing, but it becomes a category where Richard Wright is always a “black writer."

We categorize writers because libraries and bookstores have shelves, and if you ever want to find a particular book in a room with a thousand books, there has to be a system.

No one ever says Arthur C. Clark was a “white writer,” even though he was. Nobody ever says Arthur C. Clark was a “gay writer,” even though he was. What they say is “Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clark,” which can be as limiting as saying he’s gay or black or any other adjective. Should he want to write a romance novel, his publisher might balk. There are stories about things Clark wrote that weren’t science fiction, but they’ve never been published and might not even be real.

When Howard Allen Frances O'Brien wrote about vampires, she used the name Ann Rice. When she wrote erotica, she used the name A. N. Roquelaure or Ann Rampling. She was particularly good at not getting pigeonholed.

We all write alone in a room, even if we’re writing on a laptop at the end of a crowded bar. We write about what we see, which includes all the adjectives we use to describe ourselves. We don’t think of these adjectives as limiting us, but when we take that huge step between writing something and having other people read what we write, those adjectives can become bigger than whatever it is that we’re writing.

Part of what makes me think about these things is that I almost never find myself moving in synchronization with other people who look like me or live like me. Sometimes, I love how they see things. Sometimes, I hate how they see things. A lot of times, I just don’t understand how they see things. I’ve never been invited to join their team, but I don’t think I would. Teams make things complicated.

When asked about what sort of writer he was, Ray Bradbury said he wrote about “dinosaurs and rocketships.” If you have to be in a category, that’s not a bad one.