Even for people they admire, men like to test the mettle of one another. It’s a stubborn vestige of our days as a more primitive creation. However awful it may seem, it’s usually good-natured and a sign of one’s mutual respect. Jokes and pranks become a language of love.

My grandfather had two very serious-minded older brothers. One, Robert, died in France, doing his best to ferry wounded soldiers away from the advancing German Army when mustard gas overtook him and them. The other, Boyd, worked as a school principal when he got the idea that Mississippi really needed someone who sold pencils, slate blackboards, all-wood chair desks, and basil readers. Serving the very poorest state in the Union, Mississippi school supply sounded like an unlikely venture, but somehow it succeeded. My grandfather became his brother’s first employee at the newly minted business, and a coffee-colored creation with an eye to prove himself named Jim Woodson became the third.

When my grandfather died, the top of his desk was ordered and clear, save a well-worn, black leather King James bible populated with ribbons and index cards scribbled with favorite scriptures, an entirely flat pencil he’d been using as a bookmark stuck between the pages, that had been a gift from the president of Dixon-Ticonderoga Pencil Manufacturing Company, and a yellow legal pad, where he made the notes used to make his predictions for the football pool, which he usually won.

Inside his desk and the credenza behind were three rubber snakes. Three books labeled “Jokes for Salesmen,” “Jokes for Athletes,” and “Jokes for Teachers” sat beside two woven-wicker Chinese finger traps. A metal can labeled “Peanut Brittle” had a spring inside covered in cloth with a snakeskin pattern that jumped out and surprised anyone wanting peanut brittle. He had a wooden donkey that dispensed cigarettes from its anus when you pressed its head. Two boxes of “Rattlesnake eggs” snapped your finger with a spring if you tried to peek at the eggs. He had a flower that one wore in their lapel and squirted any would-be flower sniffer by means of a rubber bulb hidden in the palm of the hand. He even had a genuine buffalo nickel that had been hollowed out and replaced with a copper reservoir that would shoot a sharp stream of water out of a hole drilled in the “C” in “Five Cents” and douse the unaware.

Unable and unwilling to compete with his brother’s more serious personality, my grandfather had a pronounced reputation as a trickster and was known as such at the Methodist Men’s Breakfast Club, The Jackson Club, and the Jackson Country Club, but not the Rotary Club, which he never joined because they weren’t any fun.

In every way, Jim Woodson was the company’s third man. He became the face of Mississippi School Supply to its many African customers during the days when there was no interaction between white teachers and students and black teachers and students. Jim Woodson worked in the warehouse, but he was one of the firm’s best salesmen.

Intelligent and articulate, Woodson bore unprecedented levels of responsibility at Mississippi School Supply, a fact that annoyed some, including Mr. Ford, the treasurer, who considered him untrustworthy. My Uncle Boyd made it clear that he trusted Jim Woodson more than Mr. Ford! And that was that.

My grandfather worked closely with Jim Woodson. Something like eighty percent of our business happened between the last day of class in the spring and the first day of class in the fall when they had to get everything the school needed from the warehouse on South Street in Jackson to the classroom before the students arrived needing them. Creative and intelligent, Woodson was considered equal to whatever task was set before him.

None of Jim Woodson’s better qualities made him immune from my grandfather’s trickster side. Gregarious and performative, Jim Woodson was a religious man with a propensity for superstition that would become his undoing when it came to Grandaddy’s devilments. Jim Woodson was afraid of ghosts.

In the 1930s, Mississippi School Supply expanded by purchasing The Office Supply Company, which had offices in Jackson, Laurel, and Greenville. Advertising itself as “The Complete Office Outfitters,” The Office Supply Company soon became a dealer in electronic machines designed to make life in the modern office more efficient and productive.

Advances in electronics were constant and common in the 1940s. The Webster-Chicago Company developed an electronic gadget that promised to make the task of dictating letters considerably easier and more efficient. A busy executive or professional would simply speak into a microphone similar to the ones used for radio, and his voice would be recorded exactly as he spoke on a spool of wire. A secretary could then play back the recording of her boss’s voice while seated at her typewriter and prepare his correspondence with more precision than older stenographic methods. It was the latest thing, and the Office Supply Company had it.

The Office Supply Company was the first outfit in Mississippi to offer the stenographic wire recording device. Nobody else had ever heard of it. When the first machine arrived, all of the company’s executives and salesmen showed up at the Capitol Street store to see it. They took turns recording themselves and playing it back. Many of them had never heard their own voices before. That sounds strange to say for modern readers, but for men at the time, recording yourself was a novelty. A wire recorder isn’t exactly a high-fidelity device. The distorted and mutated playback of his own voice amused my grandfather. “It sounds kinda creepy, don’t it?” He asked.

Back at the South Street warehouse (where Cathead Distillery is now), Jim Woodson and his crew weren’t invited to the premier of the Webster-Chicago Electronic Recording Device. They were too busy trying to get the product off the freight car the train left and stacked it in its proper spot so it could be shipped to Mississippi’s Schools. Hiding one of the Webster-Chicgo Electronic Recording Devices in his office, Grandaddy had a devilish idea.

When the lunch bell rang, Jim Woodson and his crew made a hasty beeline for the cafeteria, where Aunt Annie prepared a peppery pork roast and fried cabbage. With my family being white and Annie not, it’s unlikely that she was ever my actual aunt or any other blood relation. You’ll be told that older black men were called “uncle” and older black women were called “auntie” out of respect, but I suspect it had more to do with convention than any sort of imagined respect. That being said, plenty of blood relatives weren’t as welcome in my family as Annie was. As a child, I was required to stop at her kitchen when visiting my father at work because it was necessary that I hug Annie’s neck and give her some sugar.

With the entire warehouse at lunch, my grandfather implemented his elaborate plot. Dobby Bartling and Gus Ford were in on it. All they had to do was wait.

When Jim Woodson came back from lunch, Grandaddy told him to go to the very back row of the warehouse and fetch a box of Swingline staplers. Since my grandfather asked the head man rather than one of the other warehouse boys, Jim Woodson assumed this box of staplers must be for some important customer. He walked to the back of the dark and dusty warehouse, found the box of staplers, stood in silence for a few moments, then returned with the box of staplers, which he handed to Doby Bartling, who made a face like he was expecting something, but something that never happened.

Dismayed and disappointed that something went wrong, once Jim Woodson occupied himself with other tasks, Grandaddy went back to the stack where the Swingline staplers were and retrieved the box he’d hidden there. Inside the box, he examined the The Webster-Chicago Company electronic wire recording device he left to make sure it was working. Winding the wire back and pressing “play” a ghostly voice came out over the speaker:

“Jim Woodson? JIM WOODSON! This is da lawd JIM WOODSON. I’m callin’ you to preach Jim Woodson, deny my wishes, and I’ll put a POX on your generations just like Job!” The electronic device rendered my grandfather’s voice unrecognizable. It had a wavering, haunted quality that could only be a ghost, if not THE HOLY GHOST, but Jim Woodson appeared absolutely unphased. Maybe it failed to play as planned. Maybe the volume was too low. Maybe Jim Woodson recognized Grandaddy’s voice and knew it was a prank. Whatever the case, my grandfather’s plan to see Jim Woodson run out of the warehouse whiter than he was a complete bust. He’d have to get up earlier if he was going to trick Jim Woodson.

Time wore on, and the failed attempt to prank Jim Woodson was forgotten. One morning, several months later, my Uncle Boyd and my grandfather were opening the company mail.

“Jim Woodson came to me yesterday. Seems he wants to start taking three weeks off every spring before the busy season starts.”

“What’s he want to take off for?” Grandaddy asked.

“Seems he’s taken up preaching. Here locally mostly, but he wants to start doing evangelical tours around the South in the Spring. I didn’t even know he was religious.”

Grandaddy swallowed his coffee and switched his eyes side to side toward the corners of the room.

“Did he, uh, did he say anything about how he was to take up this preaching?”

“Nope, he just said he was called to preaching, and he’d been working here so long, and the early spring was our slower season, so wouldn’t I let him have the time off? I told him it’d be fine. Why?”

“Oh, no reason,” Grandaddy said, “Jim Woodson’s a good man. People like him. He’d make a good preacher.”

Grandaddy never speculated on whether or not his failed prank had anything to do with Jim Woodson preaching the gospel, but Doby Bartling sure did, and so did Orrin Swayze and Carter O’Ferrall. The story of how Jim Campbell called Jim Woodson to preach evolved into one of the most effective ways to embarrass my Grandfather, which was fair game considering how many people he’d attacked with rubber snakes and squirting nickels.

In 1958, Jim Woodson was driving from Jackson, Mississippi, to Los Angeles, California, to preach the word of the Lord to people in California (who really needed to hear the word of the Lord judging by what I know of Lost Angeles in the late fifties), when he had a heart attack outside of El Passo, Texas. In a hospital in Texas, the Lord called Jim Woodson home. His body was returned to Mississippi, where both Jimmy and Boyd Campbell eulogized him. Five years later, Boyd passed himself, leaving Mississippi School Supply in the hands of my grandfather, Coach Doby Bartllng, and my father, who had just turned thirty-two.

I had to wait for an entire generation of my family to die off before I could tell this story. It amused my mother to no end but mortified my grandmother. The issue seemed not to be pranking the earnest Jim Woodson, but this business of pretending to be the Lord All Mighty might be a scandal. Long-time employees at Mississippi School Supply all had stories about Jim Woodson. I never got to meet him. I did meet his daughter, who became a teacher. He was much loved.

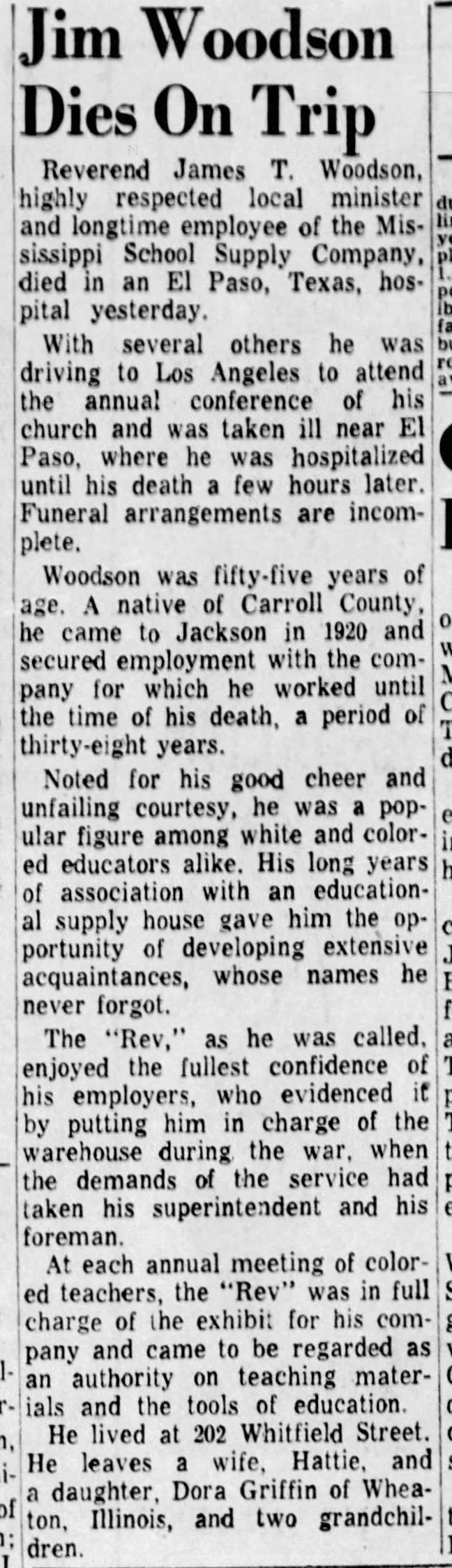

When Jim Woodson died, The Clarion-Ledger printed a six-inch death announcement on page three of the Wednesday paper, referring to him as “Reverand” and openly naming him as a business leader at Mississippi School Supply. In 1958, in Mississippi, that sort of accolade for a black man was unusual enough to be worth noting.

Telling Jim Woodson he was tricked into preaching might have embarrassed him, and that wasn’t acceptable to my grandfather. Jim Woodson believed he was doing what the Lord wanted him to, and who’s to say he wasn’t? Jim Woodson believed in what he was preaching. He believed the blood of Jesus could help people, and in the years he lived, people needed helping.

I can’t really defend my grandfather pretending to be God or deceiving a man like Jim Woodson without admitting to it, but I can tell you he loved and respected Jim Woodson. I know that because he didn’t prank anybody, he didn’t love and respect, which made us grandkids some of his most regular victims. I suspect my grandfather never had it in him to tell Jim Woodson the lord hadn’t spoken to him. Being a reverend meant the world to Jim Woodson, and Grandaddy just wasn’t willing to take that away. Everything I’ve read and everything I’ve heard from people who knew him tells me that Jim Woodson was an exemplary preacher. Maybe how he was called to do it wasn’t really the point.