Man/Bear/Pig Was Real All Along

the truth about politics in mississippi and the influence millsaps had on it

When I was a child, my mother told me that Dr. Kirby Walker was building a house one over from ours. I was excited because he’d been kind to me and given me peppermint. Imagine my disappointment when Dr. Kirby Walker, the dentist son of Dr. Kirby Walker, Superintendant of Jackson Public Schools, would be our new neighbor. In the years to come, I would learn that the son, a dentist, was a pretty remarkable and interesting guy, but in 1969, I was learning that life was a slow progression of minor disappointments and unexpected changes in weather.

By 1960, everybody in Jackson, Mississippi, knew that Jesse Howell was gunning for Kirby Walker’s job. Most people were cool with it, including Walker. Howell was Walker’s most talked about, most assertive, and most successful principal. Heading up the first junior high school in the new northeastern part of Jackson, he was a young man who made a big impression.

When the Brown vs Board of Education decision came down, there was talk of shuttering every Mississippi public school and replacing them with private ones, under the belief that private schools could do what they wanted with regard to segregation because they didn’t take public dollars. Their plan included a way to still get public dollars through a voucher system. If that sounds like the bill the Mississippi Institute for Public Policy wants for “School Choice,” it should. It’s the same bill.

Howell took meetings with people who didn’t want to integrate. Not much came of them. Most people saw the plan to shut down the public schools as either insane at worst or a fire escape at best. Literally, nobody thought it was the best plan. Besides, under Kirby Walker, who had been Superintendant for over thirty years, Jackson Public Schools was seen as one of the best school systems in America, even though they were in the middle of the poorest states. Walker was quite proud of the fact that he had brought every school in Jackson Public Schools in compliance with the Brown v. Board of Education ruling without anybody taking a shot at anybody like what happened in Arkansas and Louisiana. That sounds like a crazy thing to be proud of, but in the South, in the sixties, that was reality.

My family was in the School Supply business. From the end of World War II until my father’s death, we were the largest School Supply outfit in the world. Most of that is due to the fact that we included our office furniture and textbook sales numbers in the school supply figures. That was a legal move, but still, it was kind of a cheat when compared to guys who didn’t have these other operations to fall back on.

Everything changed in 1970. The Nixon Justice Department put his Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in charge of the Jackson public schools and pushed Walker into retirement five years before he planned to. Suddenly, the plans to give Jessie Howell a private school gained renewed interest. Kirby Walker told my grandfather that he didn’t know what the future would bring and “Tell Jim he better get those boys in private schools.” For a guy who dedicated his life to public schools, that couldn’t have been an easy thing to say.

Our family dinners always centered around the family business. In the summer between 1969 and 1970, I first heard my father call anybody a “sumbitch.” In the mad dash to open a segregated private school system to replace the integrated Jackson Public School system, there was incredible pressure on my dad to give the less-than-a-year-old boards for Jackson Prep and Jackson Academy a commercial line of credit for a million dollars each so they could open their schools on time. I won’t say who the sumbitch was, but he graduated from Ole Miss, he was in the insurance business, and he always figured he could tell my dad what to do and what to think. It almost never worked out that way.

What happened next is sort of a controversial subject. My father’s version of the story said that the contractors, in a mad dash to build the new schools in ten months, approached him with the idea of denying the private school boards credit and forcing them to get Letters of Credit from the banks. The contractors always maintained it was my Dad’s idea. I kind of think they might have been right.

The end result was that Trustmark and Deposit Guaranty wrote the letters of credit at higher than normal rates. They ate steak that night, and all the guys who thought they were going to use their social connections to force their hand had humble pie.

It’s hard to imagine how any of this is connected to what happened to Al Gore at the turn of the century, but that’s how a lot of my stories go. I guess the point is that you never know how things will turn out; the good guys don’t always win, and sometimes, you can be absolutely right and still lose.

In 1969, Al Gore was just leaving Harvard. A man of principal, he protested loudly against the VietNam Conflict, but even though his father was more than politically connected enough to get him a deferment or a position in a safe place, Gore decided to join the Army so that his fate wouldn’t be different from other Americans.

Gore appeared in uniform in some of his father’s political ads. The Senior Gore lost that election to a man who was eventually found guilty of illegally taking money from the Nixon Campaign. In the 1970’s, it was pretty difficult to escape that particular gravity well.

Gore’s roommate in college was a young actor named Tommy Lee Jones. When asked about Gore and VietNam, Jones said, “If he found a fancy way of not going, someone else would have to go in his place." I always thought the relationship between these two men could make a great movie. One ended up being the very definition of cool, while the other ended up being the definition of not cool. That they were friends is the stuff of legends. Compare Gore’s experience in VietNam with the bonespur asshole we just re-elected.

Six years after Gore lost to George Bush, the writers of SouthPark introduced the character of Man/Bear/Pig. “Prophecy” was a 1979 environmental horror film starring still young and beautiful Talia Shire in one of her few roles not associated with Rocky or The Godfather. Chemicals used by a lumber company were poisoning the water, which poisoned the fish, which poisoned the bears eating the fish, which produced a monster that looked like a cross between a man, a bear, and a pig.

Kevin Peter Hall, a remarkably gentle actor who also played The Predator and Harry of Harry and the Hendersons, played Man/Bear/Pig in “Prophecy.” The actual prophecy here ended up being about Al Gore.

In Southpark, a strange man with an unusual personality comes to town to warn the kids about Man/Bear/Pig, a monster, the result of Republican environmental policies, was alive and posing a very real threat to life and happiness in the area around Southpark, Colorado.

The boys decide that AlGore is just weird and maybe doesn’t have any friends. AlGore would even wear a costume to convince the boys that Man/Bear/Pig was real, but that just made things worse. In a plot twist worthy of Southpark, Man/Bear/Pig was real and was every bit as dangerous as AlGore said he was. In future episodes, we’d learn that Man/Bear/Pig was in league with Satan and ended up having a pretty significant presence in the Southpark universe.

In 2000, I found myself very drawn to the real Al Gore as a candidate. Although the Republicans hated him with a white-hot-hate, Bill Clinton ended up being one of our most successful presidents. The economy was good, the budget was balanced, and our foreign policy was mostly successful.

I liked Gore because he was from Tennessee, and I tend to favor my own kind. Clinton’s success over George HW Bush was seen as “The rise of the Yuppies.” I was just glad they were willing to call a boy from Arkansas and a boy from Tennessee “Yuppies.” Usually, we get left out of these things.

I also liked Gore because, even though actual scientists had been warning us about it for almost fifty years at this point, politicians in America were solidly unwilling to take on the environmental damage caused by “American Progress” until Gore. Gore wrote a book on it. He made it almost cool to talk about “global warming” and “climate change.” This was going to be a very different sort of presidential campaign. That Gore was something of a nerd who struggled to show affection didn’t phase me. Those are words I understand.

My loving spouse fully supported my supporting Gore. It was nice to have her approval for a change. In those days, I was still pretty sure that I was a Republican. What I’ve really always been was a centrist. Which party better describes that keeps changing.

Somewhere along the way, I realized I really liked George W Bush as a person. He sometimes drank too much, made bad business decisions, and sometimes trusted the wrong people, but he shot from the hip and spoke from the heart, and I admired that. I was ready to publically change my position and take the spousal abuse that would follow, but I was having doubts.

A lot of people thought Bush was an idiot. I thought he sometimes struggled to put his words together when he was speaking. Yet again, it was a trait I understood because I shared it. I knew the 2000 election would be a horse race, but nothing could have prepared us for what actually happened.

The closest election of the American Experiment, the 2000 battle between Al Gore and George Bush, came down to a few counties in Florida. Recounts were ordered. It soon became an issue that so many ballots in Florida were either incomplete or improperly filled out. By Florida Law, they would be thrown out. Lawsuit after lawsuit followed. Bush took the position that he would rise above it and let his team handle it, a management trait he’d be criticized for many times in the years to come. Gore was deeply involved in the process.

Ultimately, Gore realized he had a few more legal avenues to explore, but he knew it was tearing the country apart. Losing his most recent appeal in the Supreme Court, Gore decided to act in the country’s best interest, not in the interest of his personal political ambitions, and he stood down. The ballots, hanging chads and all, were stored away.

Ten years later (after the Southpark debut of Man/Bear/Pig), some historians got permission to open the boxes of ballots again and see what really happened. Using mostly graduate student labor, they recounted the ballots and sorted them according to ballots deemed “acceptable” according to Florida law and those that were still legitimate ballots, but deemed “unacceptable” according to Florida law because they were incomplete or improperly filled out.

What they found was that according to the way Florida Law was written in 2000, Bush won most of the complete and correctly filled-out ballots, but based on ballots that were improperly filled out but still legitimate, Gore won by a considerably larger margin. Considering how many people retire to Florida, the idea that some of them might be confused about filling out their ballot should not have been a surprise. According to the law, Bush was president, but according to the actual will of the people (at least the people who bothered to vote), Gore won by a larger margin. Just like in Southpark, Man/Bear/Pig was real all along.

I never discussed the outcome of the 2000 election recount with my spouse because she was no longer my spouse. I did discuss it with her father. He was a brilliant guy who secretly remained friendly to me.

They used to call my father “Kingmaker.” It annoyed him a lot more than he let on. Whenever anybody used that word around him, he insisted that they meant Warren Hood. They were actually really good friends and more often shared the same worldview, even though they were sometimes on opposite sides of an issue. In the years when Mississippi worked best, what I call our “Camelot years,” it worked because men of good will learned to work together and resolve things, not in the best interest of their parties, but in the interest of the people of Mississippi.

The people of Mississippi weren’t always led by men who had their best interests at heart or didn’t have the best interests of all Mississippians at heart. It was hard to find people willing to serve the whites and the blacks rather than reap the political benefits that came from pitting them against each other, but for a while, it happened just that way, and we progressed.

Daddy liked to pick guys when they were young and then be prepared when they were ready to ascend to power. Sometimes, it took a while. William Winter ran for governor four times before winning. How he absorbed all those rebukes is a testament to him as a man. A lot of it probably had to do with his wife, Elise.

My mother used to joke that “If Jim ever decides to run for office, he’ll have to do it married to the next Mrs. Campbell.” She meant it, too. Being the wife of a candidate is not all roses and cocktail parties. In my life, three guys were married when they were elected and divorced when they couldn’t run anymore. Another was shot in the leg by his wife, who wished she was a better shot. The paper reported that she had a nervous breakdown but didn’t report the gunshot. She spent the rest of her life in a sanatarium. First Lady of Mississippi isn’t the best job.

There were two guys my dad told me to watch out for because they might be governor one day. One was Andy Mullins. Andy had been a football coach at St. Andrews when he was younger than my nephews are now. The Mississippi Private School Association (now the Midsouth Association of Private Schools) was determined that St. Andrews would join their organization so the Saints would play football against Jackson Prep and the Council Schools. At the time, they were among the most powerful organizations in Mississippi. Since it was a football decision, the board and the faculty of St. Andrews left it up to Mullins to decide as best he could.

A graduate of Millsaps College, Mullins wasn’t willing to sign the Saints up for a segregated sports league. He stood down all these men who felt sure they could beat down this young fella with the force of their will, and he found us other people to play in football. There were times when these small-town teams we played just about beat us to death.

The last game I ever played at St. Andrews almost had to be called because we had so many injuries it was unclear if we could put eleven men on the field. We got our ass beat pretty good, but at sixteen and seventeen, we didn’t violate our principles, thanks to Andy Mullins. Sometimes there are things worse than an ass beating. Andy left St. Andrews and went to work for William Winter as one of the fabled “Boys of Summer.” That’s when my father marked him and warned me to watch his progress.

The other fella dad thought would be governor or higher one day was Brad Chism. Millsaps had always ridden the peaks and valleys of Mississippi’s past. Sometimes, we absorbed some pretty rough blows. Some of our faculty received death threats when they let some Millsaps Students protest a police brutality case at the State Capitol. It wasn’t the first time somebody said they would kill TW Lewis because of what he believed. It never seemed to slow him down.

Millsaps suffered from the perception of being “too liberal,” particularly when it came to issues of race. Sometimes, it was hard to raise the money we needed. Sometimes, it was hard to get the students we wanted. Sometimes, it’s better to take an ass beating than to violate your principles, so Millsaps chose that path.

In the 80’s, Millsaps decided to take the audacious step of trying to copy the Harvard School of Business in humble Mississippi. With hardly any money and facing all the challenges that came with trying to do anything at all in Mississippi, Millsaps rested on the academic reputation they built up over the last seventy years, the reputation a young professor from New York who came to Mississippi and build what became known as our “Heritage Program” and the sheer irresistible force of George Harmon’s will, we made it happen.

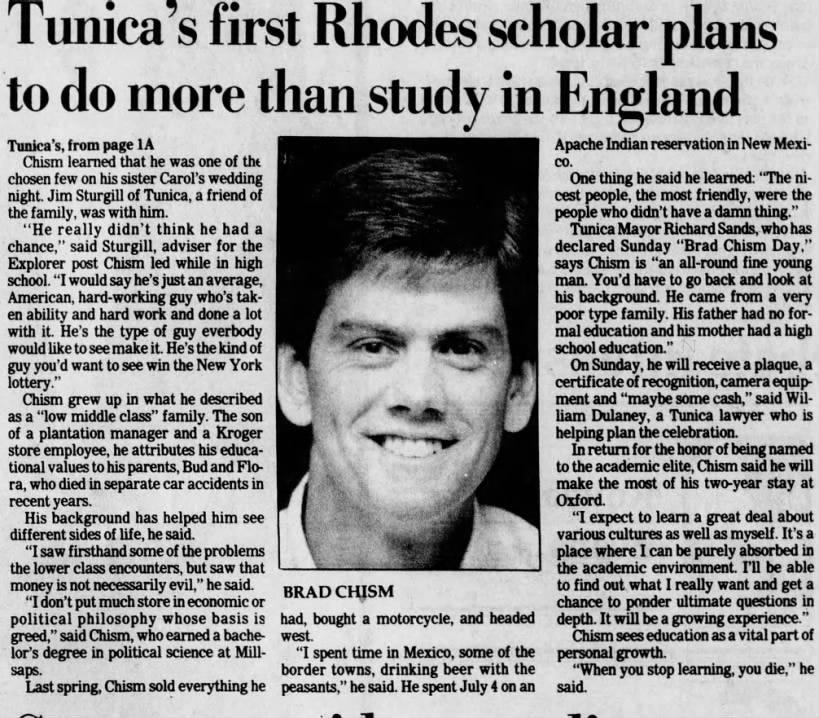

Internally, we were pretty proud of what was happening at Millsaps. I was still in high school. Externally, Mississippi wasn’t exactly known for its scholarship. Ole Miss had a Rhodes Scholar in 1927, but not much since. Millsaps had one three years earlier but not much since. In 1982, George Harmon released a statement that Brad Chism would be the school’s fourth Rhodes Scholar. He was also proof that the reimagined academic structure at Millsaps was not only working for us, it was working for the academic world.

It wasn’t unusual for Daddy to eat supper left on the stove for him in the kitchen. Sometimes, his days lasted longer than others. Sometimes, I stayed up and sat with him while he ate. “You watch this Chism fella,” He said. “He’s gonna be governor one day, hell, maybe president.”

Daddy died before he could see the results of his political predictions. I don’t think it’d bother him to know he was wrong about Mullins or Chism. Neither of them ever ran for office, but both of them kept their fingers on the political pulse of Mississippi and the United States.

Sometimes, I like to imagine a history where both Mullins and Chism ran for governor. Maybe they would have extended the Mississippi Camelot period by at least sixteen years (presuming they would get two terms each.) They had very different personal styles, but they both had (and have) a very clear vision of what they wanted for Mississippi. We could have done (and did do) a lot worse.

So what’s the point of all this? Politics never turns out like you expect. Politicians never turn out as you expect. The future’s not written until it’s the past. Sometimes, Man/Bear/Pig is very real, but you realize it is too late to do anything about it.

I could never be the man my father wanted me to be. Part of that is because, when I was young, his career meant he didn’t have the time to learn what sort of boy I really was, so we both spent most of the time we had dealing with this imaginary boy he thought I was. I spent most of my life intently trying to learn and understand the things he tried to teach me. I think I’ve done ok with it.

The truth is the truth, even when it’s Man/Bear/Pig. Sometimes, it’s better to take an ass beating than to sacrifice your principles. People from Mississippi will astound you by how wonderful they are, but not always.

I had forgotten about Jesse Howell. I lived in the Broadmoor subdivision that was adjacent to Chastain. The land where the school was built was undeveloped (there were some mules and a black family living there) when we first moved there, and the interstate 55 was not yet built. My friends and I played on the big dirt moving tractors when they cleared the land for the school, and played *inside* the new bridges that crossed Northside Drive when I-55 was built. A few years after Chastain had been built, someone spray painted in large letters "To hell with Mr. Howell and his evangelism" onto the street-facing side of the gym." I didn't know what evangelism was until then and it was my first experience of graffiti. I don't think I ever learned who had written it or what they were mad about, but it sure was a shock to the neighborhood.