I’m older than the moss on the trees, and I’m still learning about things that happened in the days around my birth.

Starting the second week in June, 1963, my mother was grateful it was just about time for me to be born. Driving to Jackson, Byron De La Beckwith would have known that there were business and religious leaders in Jackson who spoke out in favor of tempered and measured acquiescence to the demands made by the NAACP.

I have to wonder if part of what drove him to action was the feeling that white men in Jackson were too weak to hold the line, that it would take outrageous action to shock them back into supporting the old ways.

One of the white men they blamed for this was Rev. Ed King. If you knew King, you’d know he was against measured and tempered anything; he wanted immediate and unconditional acceptance of the NAACP's aims. He wasn’t even from Jackson. He was from Vicksburg, but most of his protest activity was in Jackson.

Depending on who you talk to, men either wanted to frighten King or kill him, but either way, they thought they could force him to stop what he was doing. They couldn’t. He wore the evidence of their failure on his face for the rest of his life.

Jerry Mitchell said something on Twitter today that I never knew before. He said that the Citizen’s Council paid for the legal defense of Byron De La Beckwith in both trials. When he was alive, Billy Simmons represented his career to me as a non-violent protestor, which he maintained he had an absolute right to do, whether I thought he was right or wrong. I had no choice but to agree. No matter how vile I thought some of the things he said and wrote were, he had a right to say them.

For me, Simmons was one of the most interesting characters in this story. He was like two people. One was this quiet scholar who could speak for hours, if not days, about the golden age of the Greeks. He knew more poems by heart than I did, and his library put mine to shame even before I gave most of mine away. On the other side, he said and wrote and believed some of the most horrific racist things I ever experienced. Even now, it’s very difficult for me to connect these two sides of him.

In some ways, I guess that’s how I feel about Mississippi. Some parts of Mississippi are horrific and make me want to deny I’d ever been there, and other parts of Mississippi make me proud to have been born here and proud of what Mississippi produced.

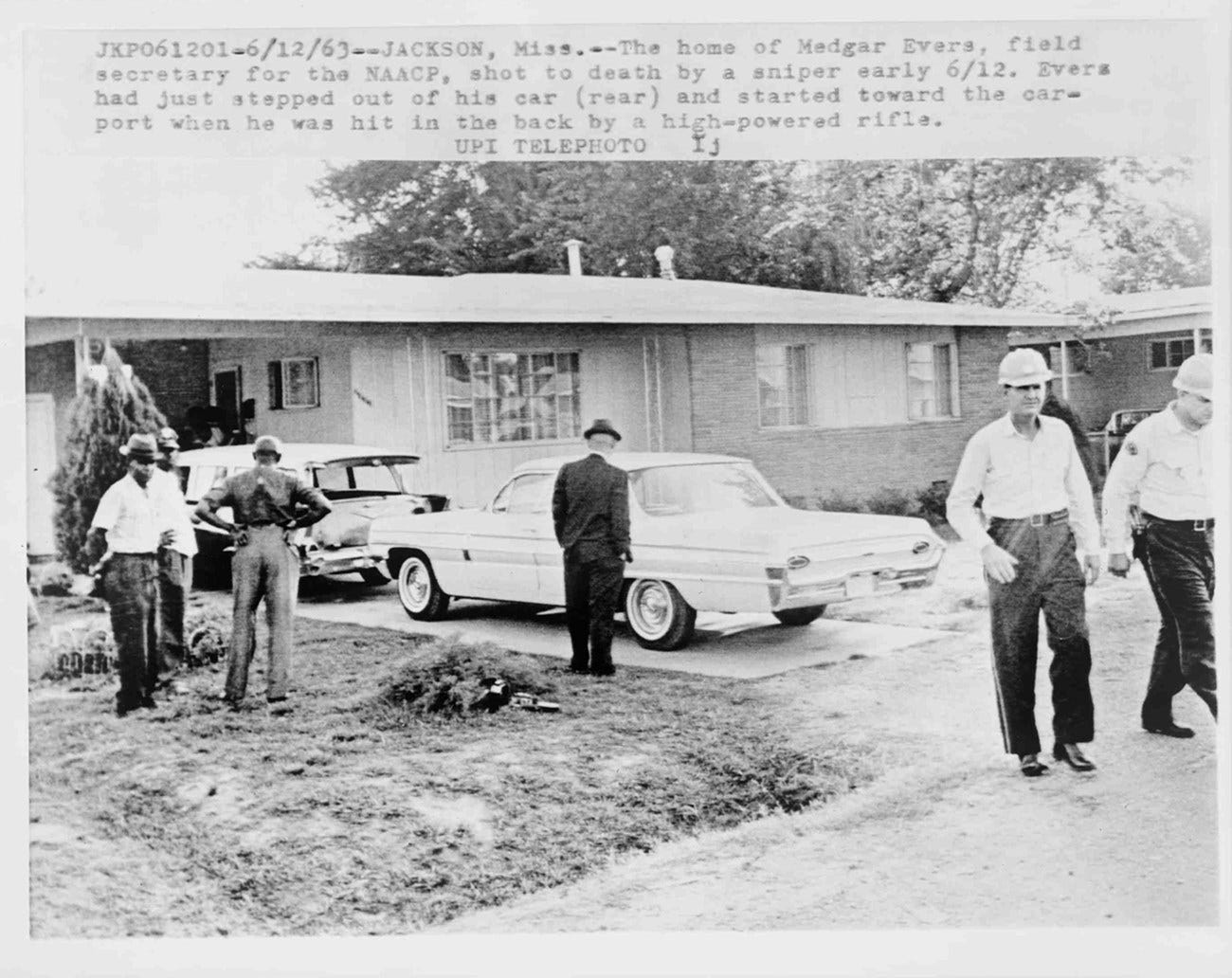

1963, the year I was born, changed Mississippi forever. It started with a murder, an assault, and a birth.