The last time I saw Leland Speed was about a year and a half before he died. We were downtown. I lived in one of the Art Deco towers, hiding from the world. It had been a few years since he’d last seen me. I put on weight. My hair and beard touched my shoulders, and my right leg hadn’t worked properly for years. I said, “Hey,” but I don’t know if he recognized me.

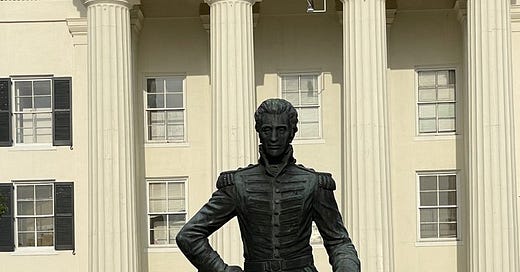

To my left was a cluster of buildings he raised out of the ground, once the pride of Jackson. To my right was a statue his mother sculpted of Andrew Jackson and his stepfather cast in bronze. Before becoming a real estate magnate, his father had been mayor. After serving as mayor, he had the idea to turn some hills near Bobcat Creek into a swanky neighborhood like the ones in Dallas and call it “Eastover.” I always thought it was funny when people from Mississippi decided to be swanky. One of the richest guys I knew was pretty proud of the fact that he was a country boy who got lucky with a sawmill.

When I was a child, about all I knew from Andrew Jackson was that song. They made us sing it at camp.

In 1814 we took a little trip

Along with Colonel Jackson down the mighty Mississip'

We took a little bacon and we took a little beans

And we caught the bloody British in the town of New Orleans

We fired our guns and the British kept a-comin'

There wasn't as many as there was a while ago

We fired once more and they began to runnin'

On down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico

Six years after the Battle of New Orleans, people in Mississippi decided to rename Lefleur’s Bluff to Jackson in honor of the fella who made the English scatter like rabbits. Ironically, there was already a peace treaty when the Battle of New Orleans happened, and the news traveled slowly during those days.

It turns out that Andrew Jackson was something of an asshole. He signed the “Indian Removal Act,” which culminated in the “trail of tears.” Mississippi never had much luck picking heroes.

When I was a child, Mrs. Speed invited me to her home to see where she made sculptures. I walked down Meadowbrook to her house by myself. She was working on a ballerina figure. I’m sure she told me who it was for, but it’s been a while, and I’ve forgotten. Her maid gave me something cool to drink, and I got to see all of her sculpting tools.

On the way home, I cut through Warren Hood’s yard. Mrs. Elsie was in the back, spraying down some flowers with a hose. She acted like she was going to squirt me but didn’t. I wouldn’t have minded. There were plenty of times when I emerged from the woods between our house and the Hood’s soaking wet and worse. As a child, it never occurred to me that these were anything more than just people in our neighborhood. I knew them, and I knew their maids and yard men as well. In 2024, that probably sounds like a pretty disreputable white privilege, but in 1975, it was pretty normal in that part of Jackson.

People in Mississippi are part of several families. There’s the family you’re born into. The people who raise you and share DNA with you. Then there’s your church family. They saw you baptized. You had a school family that included your third-grade class and, ultimately, wherever you went to college. If you stayed in Mississippi, your college family counts. If you went anywhere else in the SEC, you might be an enemy. If you went to any other college in the world, you were just an alien.

People in Jackson also belonged to a banking family. There were two. First National was the oldest, and Deposit Guarantee was the largest. Even if you didn’t know anybody who worked at either bank, your parents still had a checking account somewhere. You either had a blue frugal plastic bank from First National or a “Grow with us” t-shirt from Deposit Guarantee. When I was in fourth grade, they got about a hundred kids whose parents were involved with Deposit Guarantee to shoot a commercial inviting people to “Grow With Us” on a hill leading into Belhaven Heights. I was in the First National family, so I wasn’t in the commercial.

Banking families were pretty incestuous. Most people had dealings with both banks. At Christmas, they had a massive party in the Deposit Guarantee Plaza building with tons of food, and then just about everybody used the secret passage from the DGB Plaza into the First National building and had Christmas there, too.

We usually started at DBG and then made our way into First National, with the Christmas tour ending in Bob Hearin’s office. He usually didn’t spend much time at the parties himself. There was always an air of tragedy about Bob Hearin the entire time I knew him. His protegee and heir apparent, Ben Lampton, was killed in a car accident in England. A few years later, a guy who lost money investing in School Pictures Inc. Kidnapped and killed his wife. I lost money in School Pictures Inc., too, but I was never so mad about it that I wanted to kill anybody.

Bob Hearin could always be counted on to have a cigar. There were a number of guys in Jackson who were famous for their cigars. My grandfather was for a while, but his wife and his brother conspired to make him switch to a pipe because they said it was more dignified. One of my favorite cigar chewers was Toby Trowbridge. I used to listen to AM radio just for the chance of hearing Toby Trowbridge doing a Van-Trow Oldsmobile commercial.

I was more than a little sad when I saw Mr. Speed that last time. Not only had I declined a great deal since I’d seen him, but the city, our city, our home had declined a great deal as well. People wanted to tear down the statue of Andrew Jackson that his mother made that stood in front of City Hall, but the city didn’t have the money to do it. I didn’t care for Andrew Jackson either, but the idea that the city was so disorganized that they couldn’t afford to take the statue down really bothered me.

I hear all the time how Democrats took over Jackson, and that ruined it. That’s a great theory, but it’s not true. Jackson is today about as democratic as it was in 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990. We’ve always been a Democratic city. The next theory is that “democratic” is a dog-whistle word for black (which it is), but there again, it’s never been true that Africans “took over” Jackson. Their population never experienced a surge that might suggest them taking over. In the last twenty-five years, their population has been shrinking at a rate that’s made the population of Jackson unsustainable.

“White Flight” is given as a pretty common explanation for what happened to Jackson, and that’s actually true, although the causes aren’t as straightforward as you might think. The first big hit came when we were ordered to desegregate our schools by force in 1970, but there were other factors as well. After the Easter flood, a lot of people had no insurance and found it less expensive to start over in Rankin County. After that, once the snowball started rolling, a lot of people who weren’t actually racist sold out and moved because most of their wealth was in their homes, and their home’s value was dropping quickly.

Now, we’re in a position where Jackson, like Birmingham, Memphis, New Orleans, and similar cities, is mostly a few upper-middle-class neighborhoods and a lot of very poor neighborhoods. Everybody else has gotten the hell out.

It made me really sad to see Leland Speed in a declined Jackson. My dad was dead. Warren Hood, Bob Hearin, Rowan Taylor, Brum Day, Toby Trowbridge, and so many others had died before us. At the time, I was kind of hoping I’d die before Leland Speed. I felt like whatever I was going to put into the world I’d already given, and the way things worked out, it wouldn’t have mattered anyway. The “Bold New City” didn’t seem very bold or very new. We seemed like we were barely holding on by our fingernails.

There came a moment when I had to decide that I was either going to die or I was going to fight back. What made me want to fight back was the memory of all the people who had been kind to me as a child. People like Katherine Speed and Elsie Hood. I don’t think you can kill a community like that. It may go fallow for a while, but the roots are strong, and growth returns.

So many of the people I would want to read my stories can’t because they don’t live on this plane anymore. That makes me sad. They live in me, though. Maybe my home can find a way to be bold and new again.