Lord George Gordon Byron, the sixth baron of Byron, said, “All tragedies are finished by a death. All comedies are ended by a marriage.” In 1992, the Campbell family endured two weddings and a funeral—my father’s. If the year were a play, I’d say it’s two to one in favor of a comedy.

My sister had a respectable number of beaus, but compared to my storied and troublesome romantic history, she was a novice. In the end, it came down to two noble combatants. One was an Army Ranger, the other was a local lawyer. One became my brother-in-law, the other became known as “The Prince of Darkness,” mainly by my brother-in-law, but I went along with it.

It wasn’t my place to have an opinion or a preference, but I did. The Ranger, despite his corps’ legendary toughness, I found out was frightened by aligators when you could see their red and green eyes coming at you in the dark at Mayes Lake, and in a bar fight, despite his training, he was pretty much useless, so I stuck with Inez who had a short length of transatlantic cable that was about four inches in diameter and weighed at least ten pounds. It would have stopped a gorilla. We don’t actually have gorillas in Mississippi, but the Fauk monster visits some, and then there are wompus cats.

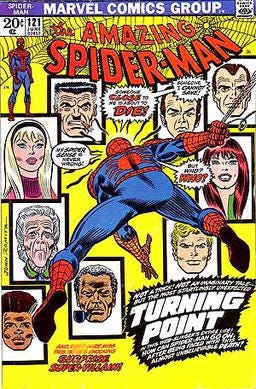

The other contender knew every issue of Famous Monsters’ magazine and still had the 1973 issue of “The Amazing Spider-Man” where Gwen Stacy died because Spider-Man couldn’t save her in time.

For all his good points, which were mainly the comic book thing, Jay was losing the battle. The Prince of Darkness did adorable things like buying a bottle of champagne to take on his flight to Jackson for a council with her highness, but forgot that airplane storage compartments are unpressurized, causing the champagne bottle to open itself and spill its contents on his clothes.

There were a number of times when I would meet the eventual winner of this contest somewhere that had beer, so he could explain that we were friends, but he was giving up on his courtship of the princess. He may have been worried I would question his manhood, which I did, but not so you’d know it. Nobody likes a quitter.

One day, I got a call. “Hey, can we have a drink?” We’d been through this before. I called my mother.

“Hey, Jay called. He wants to have a beer. Are they broken up again?”

“You need to go.” She said. My mother could be cryptic and immovable.

“Is he ok? Is there something going on?”

“You need to go. Just sit and listen to what he has to say.” That suggested this meeting might be something I had hoped for, so I went.

No great rivalry goes on forever. “I want to ask your sister to be my wife,” and it was settled.

Almost immediately after, my brother’s girlfriend began dropping hints that she wanted a ring. Dropping hints with a sledgehammer. She was pretty and nice enough, but clearly had her own agenda.

My mother and my sister were generally co-conspirators for pretty much everything. Both were exhaustingly social creatures. Combining my sister’s friends, my mother’s friends, my father’s friends, and the seven or eight friends Jay had, the invitation list soon grew to over a thousand. They had to use a personal computer to manage the list.

As the gifts started to come in, they first filled every spot on my mother’s dining room table, with both leaves in. Then the buffet, then the credenza, then a folding table with a tablecloth in the living room. I don’t think they meant to have the wedding of the century, but it was shaping up that way.

Nobody in my family is the social conquest type of person, but we have a way of becoming known, despite ourselves. Bert Felder, the head minister, would marry them.

Planning for this tuxedo invasion, my father parked his Oldsmobile 98 in front of the Bishop’s House, across from Galloway United Methodist Church. My father had a theory about cars. They shouldn’t draw attention to the driver. He liked Oldsmobiles, and Toby Trobridge, who ran Van Tro Oldsmobile, had been a longtime friend of my grandfather.

During the rehearsal, a vandal broke in and stole everything he could find in the car, which turned out to be a cloth bag with daddy’s sweaty clothes, underwear, and shoes for when he used the indoor track at the YMCA. He was pretty frustrated and visibly angry. My mother defused it by saying, “Well, you know, crime doesn’t really pay,” a reference to the smelly jockstrap the thief ended up with.

Daddy rented out the Country Club of Jackson for the reception. He’d had a hand in its design, which is why it was very, very mid-century modern. They’ve tried to soften that look since then. I’m not sure why. The only thing my father contributed was that he desperately wanted a whole poached salmon like he’d seen at another party. That and a check, of course.

Having not checked the invitation list, at the reception, I noticed that a good forty percent of everyone I’d ever had carnal knowledge of was invited. I mostly hung out in the reception, where a waiter would bring me something in a glass.

The plan was for the happy couple to attend the reception line, have a dance, get something to eat, cut the cake, take some memorable photos, and then toss parts of their costume into the audience. That never happened.

The reception line was out the door and into the hall. That’s all they did all night. I counted three former governors in attendance, and two also rans. I was satisfied getting smashed with the groom’s sister and best friend.

The pilot for the Mississippi School Supply Company King Air was fairly a member of the family. He and his co-pilot donated their time to fly the happy couple from Jackson to New Orleans so they could honeymoon somewhere tropical.

The weather didn’t cooperate. Considering what happened with the Stribling-Puckett plane, everyone was super careful about my dad’s plane since it was the same model. Into the storm, the pilot and co-pilot drove the couple to New Orleans in their own car.

Two months later, we had the second wedding. That bride and her mother didn’t have the social network my sister and mother had, so the wedding was held in the chapel at Galloway. The reception was still at the Country Club.

In a losing battle to keep me happy in Jackson, my father encouraged me to remodel my house. One day, having our after-five o’clock toddy, he said he would help me pay for the remodel once he had finished paying for the two weddings. I said I would rather he didn’t. I didn’t see it as a competition. Plus, I was hoping to rent the house out when I moved, which is something only he and I talked about.

Two days before my sister’s birthday in April, I came to work late. I had been working to find new jobs for the people who worked for me and shut down my department. It wasn’t making any money, but I was also determined to leave Mississippi forever. One by one, I fired them, taking them to dinner where they chose as I did. One wanted to go to 400 East Capitol which was run by the people from Nicks. I think she knew it was the most expensive place in town.

A note on my desk said, “Your dad called.”

Getting a coffee, a panicked voice came over the Public Address system. “Does anyone know CPR? Come to Mr. Jim’s office now!”

I knew Daddy was meeting with some guys from the National Purchasing Association, which was my other job. One of them was a heavy drinker from Maryland. That’s not why they needed someone who knew CPR.

Dictating a letter to Rober Wingate, Rowan Taylor, Charlie Deaton and Ross Bass about a planned fishing trip, Daddy’s heart stopped. It just stopped. No pain. No convulsions, he just left us. After a few quiet moments, Phyllis, his secretary, said, “Did you want to take a nap? Are we finished?” and he slumped over.

On the floor, my brother worked frantically with CPR. Pat Ross, our top School Supply salesman, took over. For about twenty seconds, Daddy began breathing again, then stopped again.

The ambulance came. They shocked him. They shocked him again. They continued compressions as they loaded him into the ambulance.

Many years before, My Uncle Boyd and Mr Kennington took a trip up north to ask some Yankee Nuns to see if they could come to Mississippi to open a hospital because all we had was an infirmary. That visit became St. Dominic’s Hospital. My father was Chairman of the Board.

Much like Millsaps, where Daddy was also chairman of the board, the staff at St. Dominic’s were fairly close to being a part of our family, especially the nuns. Nuns like baseball, and they like beer. They were among the most loyal Jackson Mets fans.

From my car phone, I called the woman I had been engaged to before any of these other engagements, but broke it off. She had bipolar disorder, but wouldn’t take treatment, making things very complicated. She wasn’t home.

At the hospital, with the entire Missco Board, the entire St. Dominic’s board, and my family, I was approached by Sister Josephine Therise. She wanted the family to meet in the chapel. Daddy was declared dead. My sister asked if she could spend time with the body. I never asked how that was for her. Some memories should be kept secret.

My mother was on a whirlwind car tour of Florida with her niece. My cousin Libby didn’t have a car phone. Leaving a message with her mother, my Aunt Jo, they told Libby what happened, but she agreed they shouldn’t tell my mother until they arrived in Jackson, about five hours later.

Mother’s home filled up with men. Jane Lewis, Linda McCarty, my cousin, and Dero Puckett commandeered the kitchen. Ben Puckett kept saying, “How ya doin’, bud?”

Waiting for my mother to arrive, Billy Neville, who founded The Rogue and Good Company, said, “Let’s go pick a suit for your daddy.” Billy Neville dressed pretty much all the men there. Daddy’s suits were all blue or grey, with the exact same tonal value. He had a Searsucker suit, but didn’t wear it often. I’m pretty sure Billy was trying to distract me. We often had cocktails at Scrooges, across the hall from the Rogue. Like daddy, Billy worked till about nine o’clock.

My cousin Libby called from Canton. They’d be in Jackson in about thirty minutes. Jack Flood, Leon Lewis, and Ben Puckett waited in the driveway to greet Libby’s car, with my mother in it. Her house was filled with men.

Later, my mother would say that when she saw the men in her driveway, she was certain one of us kids was dead. Probably me, but when Brum Day walked out, she knew it was my Dad. Brum was Daddy’s friend from KA at Ole Miss. When Ben Lampton died, Bob Hearin had been grooming both Daddy and Brum to replace him. When he asked Daddy, he said that it really should be Brum, and he couldn’t leave his father.

The funeral reception was at Wright and Ferguson. Two governors and a senator stood in the line that went out the door, down the hall, down the stairs, and out into the parking lot. One of my exes came. I held her tightly and apologized for pushing her away as hard as I had.

Clay Lee, who baptised my sister, preached Daddy up to heaven. Anna McDonald sang an old Methodist hymn he liked. They put my daddy in the cold, cold ground, near his daddy. That cemetery had sort of islands of green where they had low-profile markers. On the next island over was the little girl from next door who died in a car wreck.

About the only person who really knew how miserable I had become was my father. For two years, we’d been discussing an escape plan where I'd move to Los Angeles and begin taking film writing classes at USC, which I'd been accepted into two years prior but had never acted on.

Daddy considered writing an unsafe profession. He reminded me of all the writers who either drank themselves to death or swallowed a shotgun like Papa Hemingway. I had advanced dyslexia, advanced ADHD, and I stuttered. Being in business with him would be much, much safer.

Even though he regularly and intensely tried to talk me out of it, he was determined to support me. We would tell my mother when an actual date was set. In the midst of two such notable weddings, building the Olin Science building at Millsaps, and the growth of the National Purchasing Association, it seemed to me that my little problems didn’t amount to a hill of beans, so I didn’t bother my father about it much, waiting for my next birthday to start talking about it again, my next birthday, two months after he died.

Two weddings, a funeral, and a failed escape plan. I’m pretty sure that would still qualify as a comedy, in an Elizabethan play.