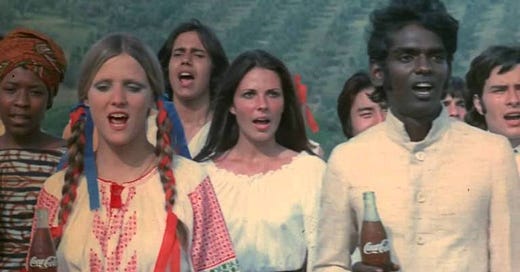

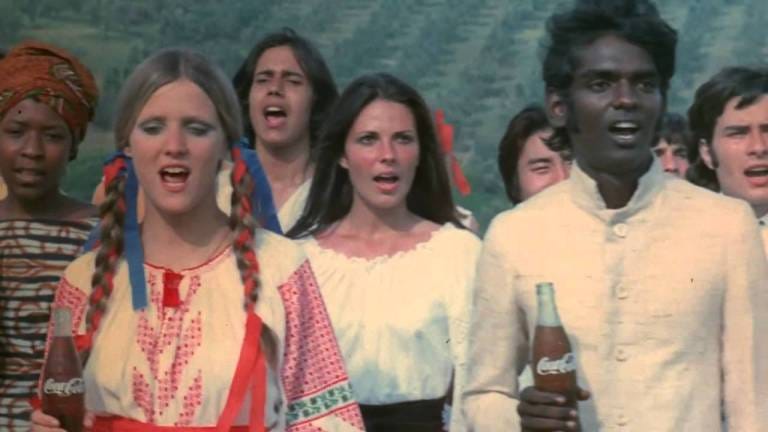

How old were you when the Coca-Cola song came out? Many of you weren’t born, so you have no idea what I’m talking about. In 1971, Coca-Cola released a television ad featuring a few dozen young people of different races and ethnicities standing on a hill and singing “I’d Like To Buy The World a Coke.”

The ad won literally every advertising award. The song was rewritten and rereleased as “I’d Like to Teach the World a Song,” with the same message of peace and racial equity. This was just one scene in the first act of the West’s massive effort to convince itself not to be racist anymore.

In the school business, you’d be surprised how many teaching aids carried the message of racial equity and reconciliation. Normally, when people talk about teachers “indoctrinating” students, I resist the notion and say it’s politically motivated, which it is, but in the case of teaching students not to have racist thoughts and not to act on racist impulses, there absolutely was a full-court press to indoctrinate students into being better human beings. It’s been almost eighty years, though, and I’m beginning to wonder if we’ve actually moved the needle much.

We’ve done a very good job of removing barriers to racial equity and inclusion from the letter of the law. There are a few instances left, but for the most part, we’ve cleaned ourselves of this kind of law, and the results are obvious. There are more non-white, non-Christian, and non-Western people in the middle class now than ever before. I’m pretty sure that was the goal. It might have been the only one we had a chance to accomplish.

In the 1949 musical “South Pacific,” Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote a song called “You Have to be Carefully Taught.” It blames racism squarely on the parents who are secretly at home teaching their little bastards to be horrible people. There are some actual studies about this, and it’s a specific and regular part of educational theory now. Teaching children not to be racist is considered an intervention to the messages their parents are implanting in them. Nobody wants to make this part of the “indoctrination” conversation, but it’s clearly at the top of the list, whether it’s working or not.

Considering the effects of genetics on anthropology is part of what led Richard Dawkins to create the idea of “Memes,” which he made a part of his book “The Selfish Gene.” The idea that we have a genetic propensity to prefer people who look like us and distrust people who don’t look like us didn’t start with Dawkins. Stephen Jay Gould wrote about it extensively. Neither man could describe a mechanism by which your genes could impact behavior, but the result seems clear.

We like to call it “racism,” but the more effective term is probably “xenophobia,” meaning “the fear of other types.”

Rod Serling used to smoke five or six packs of cigarettes a day and write two, three and sometimes four scripts a week. He’s still considered one of the most prolific writers for Television and Cinema ever. A good forty percent of his scripts involved issues of xenophobia. Both as a writer and as a producer, he was obsessed with it.

“Monsters on Maple Street” and “Eye of the Beholder” are two of Serling’s most famous TV scripts the deal squarely with Xenophobia. “Monster’s on Maple Street” aired in 1960, if that gives you any idea of how long we’ve been facing this.

Serling’s most famous script is “Planet of the Apes,” which he was the lead contributor to. Although xenophobia was part of the French novel “La Planète des singes,” Serling stripped away nearly everything else and focused on just that. Serling began to take less interest in the project as the sequels came along. By the time the series reached “Conquest of the Planet of the Apes,” Roddy McDowell’s peaceful intellectual character of Cornelius was replaced by the radical, violent character of Caesar, reflecting how the issue of confronting racism in America had grown from an intellectual enterprise to radicals like the Black Panthers.

I look back on all these efforts now, and they all seem so pitifully naive. No one can criticize America for not investing enough time and energy into this, but with that in mind, how can we adjust to not moving the needle any further than we have? We’ve successfully moved around the target of our hate, but not the energy we invest in it, and a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, everyone seems to have someone they irrationally hate.

I would suggest that the path out of here probably lies more with Richard Dawkins than with Rod Serling, as much as I love Serling’s work. It might also be time to stop blaming the parents. We’ve been trying to impress them with the message of unity for at least three generations now. They know the words. They probably know them better than you. There’s something in them that’s preventing their conscious mind from taking over, and I don’t know if that’s their fault.

It was nice believing we could sing about how great an ice-cold Coke was and solve the world’s problems. That’s literally my childhood and the childhood of millions of others. It doesn’t seem to have worked, though. Hate is still a principal part of us despite the devoted attempts of millions and millions of teachers and songwriters.

I’m not saying to give up and let the bad guys win. I am saying that maybe we can give each other a break and look for solutions that aren’t as simple as “blame the parents” because that doesn’t seem to be working.