The Foundations of Camelot in Mississippi

how lance goss avoided being called a hero

I use the word “Camelot” because it expresses an idea. Camelot suggests something purer, cleaner, and better. It sends a message, and the message is “Things are better here.” or, in the way I use it, “Things were better here, for a while.”

In 1975, Leland Speed, Warren Hood, and Charles Sewell were the lead developers in a team that opened a property they called Deposit Guaranty Plaza. It stretched from Amite Street to Capitol Street and occupied the west side of the same block where First National Bank occupied the East side.

A stark black and white monolith of steel and glass, it was the tallest and largest building in the history of Mississippi (it’s still the tallest.) It was a symbol and a message. The symbol was “progress,” and the message was presented in two parts. The first part was “We’re bigger than First National.” Their traditional rival, Deposit Guaranty, was founded on the principle that banking in Mississippi was too insular and too difficult to break into if you weren’t a First National insider. They did it at the worst possible time to open a bank, just prior to the banking collapses of the depression, but they stuck it out and made it through, and by 1975, they had more assets (loans) than First National, but not as many liabilities (deposits).

The second message was pretty clear for those with ears to hear. “Things are better in Mississippi now. Fuck you.”

If there had ever been a Camelot as an idea in Mississippi, the castle itself was the Deposit Guaranty Plaza. You could see it for miles, even on a foggy day.

Just ten years before, things were pretty terrible in Mississippi. Men were being murdered in their homes for trying to get people to use their constitutional rights. Men of God found their lives seriously threatened for trying to bring people together, and when their face was damaged in a failed assassination attempt, doctors wouldn’t treat them. The men who made Deposit Guaranty Plaza happen were pretty young when that happened. They tried, but there wasn’t much they could do to stop the injuries Mississippi was inflicting on itself. By 1975, they were ready for something new to start.

The last time I saw Leland Speed alive was forty years later. He wasn’t very far from DG Plaza. Most of the bank’s operations had always been in their original building, but by that day, the bank no longer existed. Ronald Reagan changed the rules on interstate banking, and some out-of-state pirates came along and swallowed it up. Nobody was expecting that.

Down the street, I could see the statue of Andrew Jackson, which his mother sculpted to sit in the courtyard of City Hall. His father had been mayor and was replaced by Allan C Thompson. Thompson was everything you could imagine about a racist Southern politician and more.

Some people thought Speed was an elitist because he built stuff for “rich” people. I always took exception to that. There are very few “rich” people in Mississippi. Even our richest people are peasants to the kind of wealth we’ve let pirates accumulate in America in the first quarter of the twenty-first century.

Speed was always acutely aware of the social construction of Jackson, Mississippi. He was always acutely aware of my place in it and strongly encouraged me to do better. By building things for upper-middle-class people, Speed was hoping to send the message that there’s more to Mississippi than shoeless miscreants and peckerwoods who liked to shoot up niggers. Planting flowers in a pile of shit isn’t a great solution, but it’s not a bad one.

Our relationship was never the kind where I felt like I could ask him what he thought of what became of Jackson. He made public comments that made it clear he was trying to put the best face on it he could, even when the City Council voted to tear down his mother’s statue of Andrew Jackson, but didn’t because it was too expensive. My only thought the last time I saw him was, “I’m so sorry. I know you wanted better.”

The Belly of the Beast

I was born into a world where the life expectancy of black men who stood up for themselves and demanded their constitutional rights was pretty short. Bullets would zing out of the night sky and pierce their heart while they tried to unpack their car in the carport. Their children would watch them bleed out while a white man sped away, laughing.

A lot of people, including some pretty close friends of mine, will say they’re “so damn tired of talking about Mississippi and Race!” They feel like there are more stories to tell here, and there are. I agree with them. What they don’t understand is that, in a place like Mississippi, race is the central story, whether it’s the Africans we brought over to work the black soil or the natives we killed and sent to Oklahoma so we could own the black soil, or maybe the Mexican workers cleaning chicken carcasses until Donald Trump sends them back home, race is the originating story in Mississippi.

You’ll hear it said that Faulkner wrote, “To understand the world, you have to understand a place like Mississippi.” Willie Morris included it in a book review in The New York Times, and it spread from there. The thing is, a lot of people have tried to track down where Faulkner actually said it and can’t. I’m actually more ok with attributing it to Morris than Faulkner. Faulkner is more famous, but I never thought Morris was famous enough.

1963 was a pretty terrible year for Mississippi. On the second day of the year, twenty-seven white Methodist Ministers (all very young) signed the “Born of Conviction” letter, and it was published in the Methodist Advocate magazine. The letter contained a number of things. They denounced the plan to close the public schools rather than integrate them (that issue would come up again). They denounced communism because they knew anybody who spoke up for integration would be called a communist, and they generally made the argument that God considered black men to be men. A radical statement that could (and at times did) get you killed in Mississippi.

The next month, my Uncle Boyd died, which, even though I never knew him, changed forever the possible trajectory of my life. On April 1, 1963, Allen C Thompson closed every public swimming place in Jackson, Mississippi, because the Supreme Court ruled that he would have to integrate them. Every so often, somebody will post a photograph of the Livingston Lake pool on Facebook, and somebody will say, “I remember that! Whatever happened to that?” Well, Allen C Thompson happened to that. You can fish there now, but not swim.

Eudora Welty Breaks Barriers

Millsaps College had barely over two hundred students. The Vietnam Conflict was cutting into our numbers pretty badly. At first, boys in Mississippi had trouble getting college deferments because they were in Mississippi. Some guys with weird hair in New York got their rich daddies to pay a doctor to lie and say they had bone spurs, and that got him a deferment. Anybody who had family who died in Vietnam and still voted for that guy should check themselves. He never once apologized for it. Eventually, the war made enrollment go up at Millsaps because deferments started working, at least if you were white.

In the Middle of April 1963, Millsaps was slated to host the Southern Literary Festival. The Festival still exists and has spun off some remarkable events like the Mississippi Book Festival.

While there would be events all over the South, organizers in Mississippi were keen on having Eudora Welty read as part of the festival. Welty had taught adjunct classes at Millsaps but wasn’t on the faculty as her writing career had begun to pay the bills nicely.

Bishop Ellis Finger was president of the college. Although it wasn’t part of Major Millsaps’ will, most of our early presidents were ministers, and until they changed the bylaws and asked my father to take the position, all the board chairmen had been ministers as well.

Eudora Welty was starting to feel some sorta way about integration. People think of her as this sweet little old lady, but she was tall and athletic in her youth. Anybody who doesn’t think a lady can also be a lion has never experienced either. In the 19th century, Frank R. Stockton wrote a story where a man had to choose doors, where one revealed a lady and one revealed a tiger. Stockton missed that there’s not always so much difference between the two.

In Mississippi, integrated audiences were illegal. They were not just looked down upon (although they were); they were illegal. Eudora Welty didn’t want to perform before a segregated audience.

There are different versions of what happened next. The first version says that Welty went to Bishop Finger and talked him into letting her put her plan into action. The second version is that she Spoke to Finger, and he said, “Pretend like we never had this conversation and do what you want.” The third version is that she just never talked to him at all, and it’s easier to apologize for something after you did it than to make excuses for why you didn’t.

Finger was a navy man. I tend to believe the second version is what happened. He was pretty firm about not being moved by arguments in either direction when it came to race. Like a lot of people, he wanted to move on to something else.

At the time, The Jackson Little Theater was run by an organization called the “Menopause Mafia.” It included Eudora Welty, Charlotte Capers, Jane Reid Petty, Frank Hains, and Lance Goss. Goss taught theater at Millsaps and often acted and directed at Jackson Little Theater. It’s said that he personally designed the half-height fly system the theater uses today. He was always a little embarrassed by that.

Months before, Goss had turned away black students from Tougaloo who tried to attend one of his plays. He didn’t want to go to jail, and he didn’t want to lose his job. Eudora Welty didn’t have a job at Millsaps to lose, but there was still the specter that she might go to jail. I don’t think that was ever far from anybody’s mind. Allen Thompson was willing to do some crazy things, but would he be willing to take Eudora Welty away in chains?

I think Welty was fully aware of how powerful a photograph of her in handcuffs being arrested by the Jackson Police might be and the impact it would have on the world. I’m not sure Thompson did. He never impressed me as a guy who planned ahead.

Welty was to speak in the chapel of the recently constructed Christian Center at Millsaps. Lance Goss, whose office was in the same hall, was on board but terrified. Lance was known to downplay his role in things unless it was an actual role on stage, and then he was the star.

To make her unlikely plan work, Welty enlisted the aid of two faculty members who, even though they were very young, had a reputation as freedom fighters. That sounds like a crazy thing to say in the United States in the twentieth century, but in Mississippi, it was legitimate.

T.W. Lewis and Charles Sallis had both been the recipients of death threats in the sixties. They both had children my age. There’s a brotherhood in Mississippi of people who never asked to join. It’s people that had parents where some peckerwood said they’d kill them if they didn’t change their ways. I’m in it.

As I got older, it became difficult to distinguish between my voice and my father’s voice on the phone. It was especially difficult if you were some peckerwood who didn’t actually know my dad and spent all day drinking getting mad about Jim Campbell who didn’t know you existed. I’ve heard the voice on the phone as they said they were gonna kill me and then fuck me. I asked them if they had the order reversed. Peckerwoods hate it when you make fun of them. I never bothered to mention that he got the wrong Campbell when he called.

The plan was for Lewis and Sallis to run around campus like double-naught spies looking for Jackson Police or peckerwoods with shotguns and then protecting Miss Eudora with their bodies if they had to. Inside the Christian Center, Eudora Welty read “Powerhouse” to an audience that included some students from Tougaloo who had been turned away from plays in the same building before.

It wasn’t unusual to see young black people at Millsaps. Tougaloo students could sometimes take courses at Millsaps so long as they were still enrolled at Tougaloo and not Millsaps. This was a clever way to get around the segregation policy at Millsaps. They were also allowed library privileges in the years before the library spilled over into the Ford Academic Complex.

With all the worry, all the hand-wringing, and all the running around like double-naught spies, nothing bad happened. Miss Eudora didn’t get arrested. The kids from Tougaloo didn’t get arrested. I’m sure there were some angry letters and phone calls, but Miss Eudora’s plan was a success from every measurable angle. She challenged the integrated audience law, and nobody got arrested, and nobody got fired.

A lot of the success of her plan had to do with her best friends sitting on the front row with their legs crossed at the ankles, wearing kid gloves, and just fucking daring anybody to act up. Being a lady doesn’t equate to being weak. I’m kind of glad that nothing came of this business with Lewis and Sallis poking the bushes looking for peckerwoods with shotguns. There were a number of times when I really worried about their bravery. Being brave is one thing. Actually getting shot because you’re brave is another.

One thing was for certain: the ball was now in Lance’s court. Lance didn’t like or play tennis, but he would if he had to.

Lance’s Turn at Bat

Despite the influence of the Mennopause Mafia, the board for the Jackson Little Theater was not yet ready to integrate. The loss of funding and the chance of getting arrested all just seemed bad to them. When the Jackson Little Theater went bankrupt and re-opened as NewStage Theater, the first thing the new director, Jane Reid Petty, did was announce integrated audiences, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

In 1964, Lance Goss had a surprise for everybody. His relationship with the licensing agencies was such that when a property he wanted became available, he’d get a phone call before it went out in print. In 1964, that property was “My Fair Lady.”

It was not yet available for little theaters or regional theaters, but “My Fair Lady” was available for colleges. Lance had not even seen the play yet, but he had the cast album and the libretto. He waited to make an announcement until he found out if he’d be first or not. He was. Little Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, would be the first non-professional company to perform “My Fair Lady.” The film with Aubrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison also came out in 1964. Imagine if Millsaps had been the first non-professional company to put on “Wicked” in 2024, the year the movie came out. The moment had that kind of impact.

Lance’s friends wanted him to announce an integrated audience. The year before, Eudora Welty did it, and nothing bad happened. Lance resisted. It’s hard to describe his relationship with Frank Hains. They were remarkably close. You could say best friends. Frank made the sets and designed the lights for Millsaps and Little Theater Plays. His opinion was important to Lance. Saying, “I don’t want to lose my job,” wasn’t enough of an answer for friends of that caliber. Lance knew what Frank wanted, and eventually, what Frank wanted was what happened.

Once again, there are different versions of the story from here. Some people said that Lance and Frank had it planned, along with the support of other faculty members who had offices in the building. Lance’s “official version” was very different.

“Well, these students, these Tougaloo students, they were gathered outside the door to the theater. If I turned them away, they might make all sorts of noise and interrupt the performance. It was a musical, you know. So, what else was I to do? I sold them a ticket and allowed them to enter.”

Some people will hear Lance’s voice when they read that.

Whether or not there was any pre-planning, I feel pretty certain that the events of the moment were pretty much exactly as Lance described them. I have no trouble at all imagining him saying just those things, with his curious sort of half-smile after.

Whatever version of the story you believe, after 1964, the Millsaps Players were integrated, then NewStage, and then most restaurants, and Mississippi began digging its way out of a hole, which took us two hundred years to dig.

Camelot Begins. They even let me in.

In 1980, I emerged on the scene with a driver’s license, a girlfriend, and three ribbons that all said I was the strongest man in Mississippi (at least for a while.) 1980 is just a few years after the beginning of Camelot. I took my shiny new girlfriend to the Valentine’s dinner on the top floor of Deposit Guaranty Plaza. The most expensive restaurant in Mississippi. I worked summers and could afford it. The allowance from my dad’s University Club membership helped a lot. From that high vantage point, you could see the lights of Camelot twinkling in the night sky all the way to the north, south, east, and west.

Twenty years before, writers began calling the presidency of John F Kennedy “Camelot,” the play opened in New York. The song “Camelot” spoke of new times, new dreams, and new hopes for America.

In 1965, a year after Lance risked everything to integrate the Millsaps Players, The Jackson Little Theater signed a contract to put on “Camelot” for the first time in Jackson. Lance would play Arthur. During most of the Camelot period, Dale Danks, who served as the Mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, played Mordrid, the man who would eventually bring down the kingdom.

Camelot Ends. Mississippi’s Camlann

Lance Goss retired because his heart couldn’t take it anymore—literally. He knew intuitively the thing I feared but dared not mention. Camelot was coming to an end. One of the last things to be packed away was the prop he used to represent Excalibur when he was King Arthur. The sword that could not be broken would return to she who gave it. Just like in the book, a woman’s hand reached out from the waters and took it.

Of all the people in this long and complicated story, only TW Lewis still lives among us. He doesn’t hunt through the bushes looking for armed peckerwoods much anymore, but he probably would if you asked him.

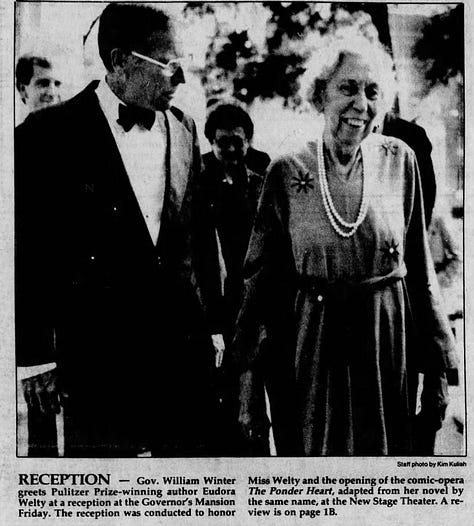

Charles Sewell, Leland Speed, Dale Danks, Ellis Finger, Charles Sallis, Charlotte Capers, Frank Haines, Jane Reid Petty, TW Lewis, and Lance Goss all dug through the briars and stinging nettles and laid the foundation of what became Mississippi Camelot. Eudora Welty was our Merlin, and William Winter was Arthur.

In short, there's simply not

A more congenial spot

For happily-ever-aftering

Than here in Camelot

But, it didn’t last.

I write about Mississippi’s Camelot for the same reason that other people write about America’s Camelot. It’s a belief in the idea that we can do better because we have done better, even if it was for just one brief, shining moment.

** Note **

Big parts of the Mississippi Camelot story came from conversations with Lance Goss after his heart attack. The parts about Lewis and Sallis might be incorrect because they were working in other parts of the country.

I try to be accurate about these things, but I'm not a journalist or a historian, and I'm often trying to weave together the stories told by older people into a single narrative.

I have no doubt that, had they been there, they would have done something.