I’ve always been very identifiable using a police description. Now, it’s because I look like Blofeld, without a cat, dangly-eye and all. I’m sure the next time I go to a concert or a ball game, Clay Edwards will say, “There’s that liberal sumbitch.” I’m not even particularly liberal; I’m just from here, and I know where the road he’s going down leads to. He does, too; he’s just gettin’ real happy to be king of the peckerwoods for a while. That’s his business, but we’ll probably have to cross swords at some point. I’ve known a lot of guys who wanted to be king of the peckerwoods.

When I was younger, I was identifiable because I was the largest thing in Mississippi that you didn’t have to pay four tickets to see at the fair.

There are a lot of stories about Billy Neville. If you listened to mine, you’d think he was a prince or something. That’s because he was. There was only one rivalry that ever really mattered in Mississippi, and in that, Billy Neville was Team Trustmark. Although he picked a side, he still dressed both sides. On any given afternoon, you’d be equally likely to see Brum Day and Bud Robinson at The Rogue and Good Company. Billy would hand deliver suits to both Warren Hood and Bob Hearin. When springtime came, Billy Neville drove to Lousiana to buy as many flats of strawberries as would fit in the trunk of his car, then deliver them to his friends at home.

“Martha, do you think Jim would eat these?” He’d ask. Jim hardly ever got a chance to eat them because we kids immediately started eating them in bowls of milk. When Daddy died, our house was filled with men for days. You’d think they were holding the Mississippi Democratic convention there. Billy Neville found me in the crowd.

“Boyd, why don’t you and your momma come with me to pick out a suit for your daddy in his closet?”

“A suit for my daddy?” I thought. “Why the hell are we getting a suit for my daddy? He’s dead! Oh…a suit for Daddy. A suit to bury him in.”

Besides Daddy, Billy Neville had to pick suits to be buried in for men he had sold them to months before on several occasions. If I start typing names, I won’t be able to finish this.

One day, Daddy said I needed a new suit, so he sent me to the Rogue. Billy Neville put a tape measure around my shoulders and made a face. “Boyd, this says sixty-four. We don’t carry sixty-four. I don’t think we can fit you.” I think it broke his heart. Billy Neville taught me how to tie a tie, and now he won’t be my haberdasher anymore. In time, that shoulder measurement dropped down to my waist, but for a while, I was too much of a man for Billy Neville to dress anymore.

My favorite thing used to be taking some coffee-eyed creature to the Mayflower and identifying the politicos as they came in. You’d be surprised how much a thing like that absolutely doesn’t impress a woman.

That was easy to do at the Mayflower. You never knew who you'd see there, across from the federal building, three blocks over from the capitol, and two blocks down from the Governor’s Mansion, the Mayflower was the nexus of Mississippi politics and culture. One night, I saw Justin Wilson eating redfish with Jerry Clower. I thought about taking a picture or getting an autograph, but I figured Theo would kick me out, so I just noted it on my pocket calendar.

It’s true that most of the dear hearts that ever captured my soul were easily identified. Black hair, alabaster skin, and blacker than black eyes, like Chani from “Dune,” but black. I would say that was a rule, but there were a couple of noticeable exceptions. One in particular was blonde, very, very blonde.

She could make a man made of stone laugh and often did. Inside that, though, was a very frail, very broken creature, and for some reason, even if it was just for a moment, supper at the Mayflower made her feel better. She believed Comeback sauce had medicinal properties. Through the years, I brought her enough bottles of it to bathe in. Maybe if she had, she’d still be with us.

Once in a booth, she’d begin listing off everything that was making her sad. Most of them were her mother and father. I used to caress her fingers with the side of my thumb while I watched the door for faces I knew. Faces that meant absolutely nothing to her.

“That’s Bill Waller.” Then, I would describe Bill Waller’s theories about higher education in Mississippi when he was governor and why he was wrong.

“Who the hell is Bill Waller?” She’d ask

“He was governor in 1972. He was part of the New South movement. He shut down the State Sovereignty Commission.” They list Cliff Finch as a New South governor. I dunno about all that. They also list Jimmy Carter and William Winter. Now, you’re getting the idea.

“Are you even listening to me?” She’d ask.

“Oh, absolutely.” Then I’d list off the last five reasons she’d told me why her father was a jerk. I have an entirely separate brain that listens to what women say, entirely independent from the brain working on whatever I’m working on. I’ve never known a woman who didn’t test that theory from time to time. They were always wrong.

“Well, shit,” I said.

“What’s wrong?”

“Ross Barnett,” I said, pointing toward the door with my nose.

“Who’s Ross Barnett? Why should I care?” She said.

“He was governor of Mississippi when I was a baby. He did some stupid things.”

“Like what kind of stupid things?”

“Like, he fought to keep black men out of Ole Miss.”

“How were they going to play football without black guys?” She laughed. Being from Memphis, she knew Ole Miss stories better than I did. But she didn’t want to talk about them. We were supposed to talk about her. I should have done just that.

“When I was a freshman, Ross Barnett invited a bunch of us KA’s to the old capitol, where we sat in the old house chambers and listened to him play the ukelele and tell dirty stories. He said ‘Heyyy Campbell!” and shook my hand. I hate being identified.”

“Why do you hate being identified?” She asked, licking the comeback sauce off her finger.

“He’s not identifying me. He’s identifying my father, grandfather, uncle, and cousin. All he knows about me is that I’m big as hell and losing my hair. If I go to a party and you say, ‘Hey Boyd!’ then I know you’re identifying me because you know me. He doesn’t know me, he’s just making connections in the Mississippi Democratic party.”

“Are you a Democrat?” She said.

“Not really,” I said, ”but even if I was, I’d never be his kind of Democrat.”

Even now, forty-something years later, it bothers me that the Governor of Mississippi was reduced to playing stupid songs on a ukelele and telling dirty stories to a bunch of drunk nineteen-year-olds from Millsaps, just so he can feel like he’s still getting attention like he’s still pertinent. If Mississippi was ever to mean something, then the governorship should mean something, and it’s hard to respect the office of the governor when he’s playing a toy guitar and telling stories about three-legged dogs and prostitutes with a lisp.

Daddy and Bill Goodman (if you put a few fingers of sour mash in them) would tell a story about the time when Ross Barnett sued Daddy because some peckerwood rear-ended one of our trucks in Crystal Springs. The judge slept through most of the opening statements, but he pulled both counselors into his office once the trial began.

In his office, the Judge addressed the governor, “Ross, Mr. Goodman here has offered your client the sum of five thousand dollars for his injury. Now, it’s my opinion that if this case goes to trial, based on the evidence Mr. Goodman has submitted, your client will lose and get no dollars at-tall. Now, explain to me, in simple terms, why we’re going to trial?”

“Your honor.” Barnett makes a dramatic pause. “If I may, while I was serving the people of the great state of Mississippi, the other partners in my firm were stealing all my clients! I have got to win a big case that people will notice to get my reputation back!” He said.

At this point in the story, I should probably inject that the entire free world knew that Ross Barnett heeled like a bitch when John Kennedy said to, and thank god he did. Ross Barnett backing down saved lives in Mississippi. I have to feel like that and other things he did while governor probably had more to do with the destruction of his practice than anything his former partners did.

When I was in diapers, they had a trial for Byron De La Beckwith for the murder of Medgar Evers. They had a trial, and De La Beckwith was acquitted. They had a second trial. During the second trial, while Myrlie Evers was testifying, Ross Barnett walked across the courtroom and shook the hand of Byron De La Beckwith, the man who shot her husband in the back. A blatant and open gesture to sway the all-white jury to acquit Byron De La Beckwith, but more importantly, to put Ross Barnett’s name back in the paper.

Now, I knew all these things, and in my heart, I hate him more than anybody I know while, in my body, he’s slapping my shoulder, playing the ukelele, and telling stories about New Orleans hookers—and saying my name. My name. Not the other boy’s names, saying my name.

“So, what happened with the car wreck?” Susan asked.

“Oh, he lost. They didn’t get any money.”

“That’s great. Can we get pie?”

You can eat comeback sauce on crackers. It’ll make you feel better about all sorts of things.

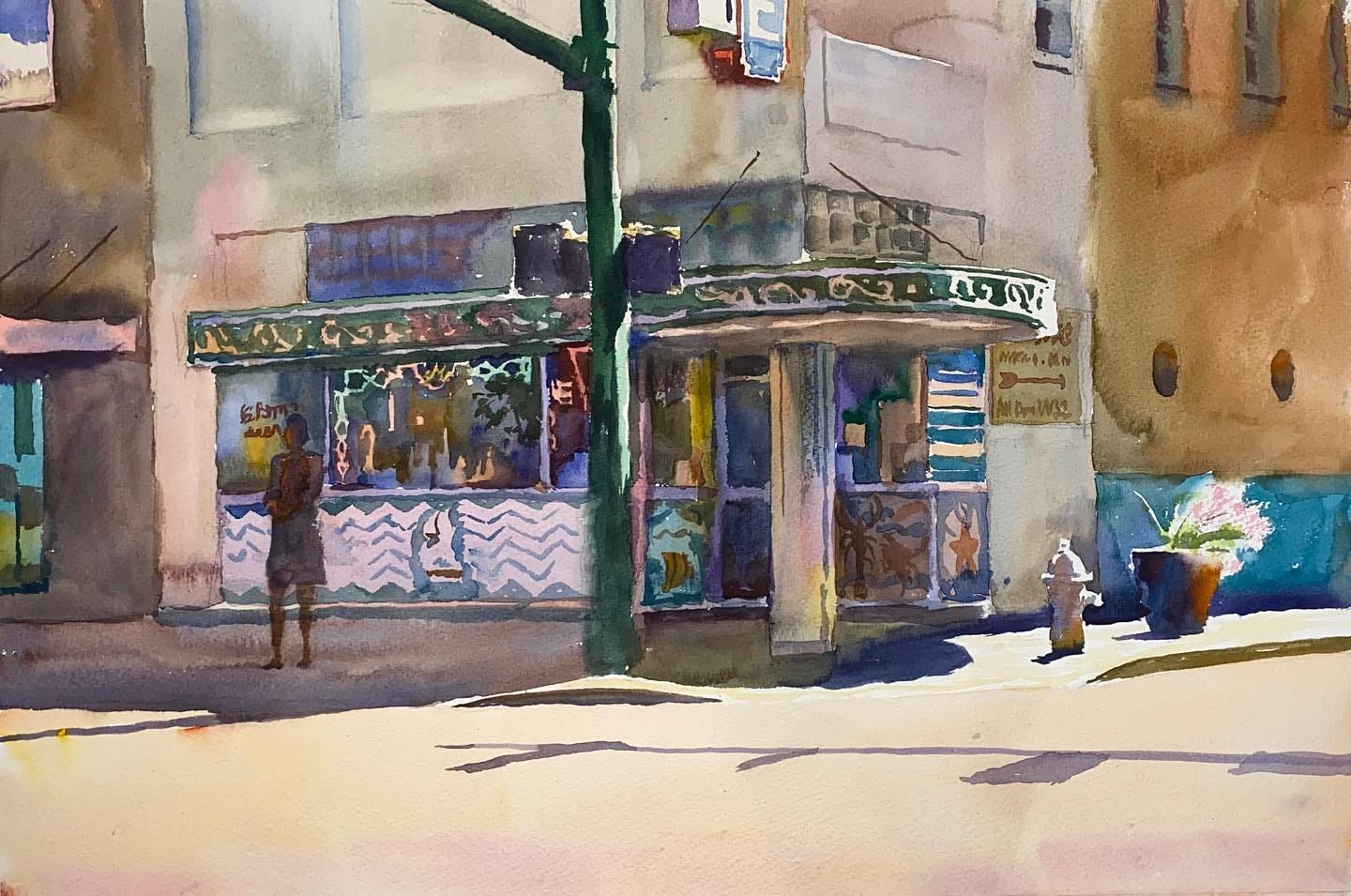

This and prints of other paintings are available at https://wyattwaters.com/

Great piece. When I heard about all the bootlickers from Congress attending trump's trial in a show of support, I couldn't help but think of Barnett shaking Byron De La Beckwith's hand for the jury to see.

What a great story!