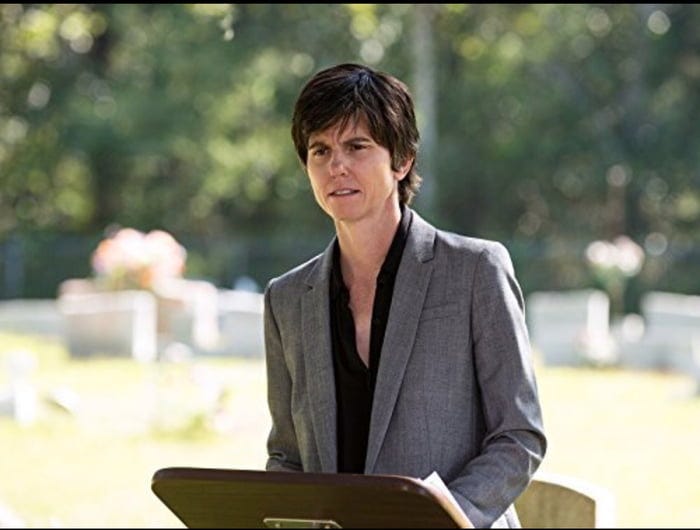

Last night, trying to sleep with words bouncing around in my head, I decided to watch the Tig Notaro special on Amazon Prime. In it, for about eight seconds, she mentioned that “some people” think she looks like Tom Cruise. Not nineteen-year-old Tom Cruise singing in his underwear in “Risky Business,” but sixty-one-year-old Tom Cruise risking life and limb to prove he can still do action movies, very few of which I can watch to the end. The last Tom Cruise movie I ever really enjoyed was “Legend,” and I enjoyed it for Tim Curry and Mia Sara (oh my god, Mia Sara!) more than Tom Cruise.

Even though I never even remotely considered it before, now that I know “some people” think Tig Notaro looks like Tom Cruise, I can’t get it out of my head. It’s stuck there forever. Thanks, Tig.

For a cranky old lesbian with pronounced health problems, I find myself resonating on the same frequency as Tig Notaro more than anybody else in comedy since Robin Williams died. I want to say it’s because she’s from Mississippi, where she was born in Jackson, in the same hospital where I was born, but ten years later. I’d like to say that, but truth be told, there’s probably a cranky old lesbian with health problems living inside of me, and there probably always was.

There are people who immediately tune me out when I start talking about the gay stuff. I get that. I really do. I’m as basic as basic straight white guys are allowed, and the idea of grown men grinding their beard stubble together always seemed pretty alien to me, not to mention painful.

The story just isn’t that simple, though. I was born too late to have any sort of active role in the civil rights movement in Mississippi. I was too little to impact any of it other than doing what I was told when they integrated my school, but it was always around me; it was always a part of my life. I grew up seeing guys like Ed King and James Meridith casually at church or the grocery store or football games and wondering what it must have been like to be them, and, if I’m honest, I'm rather glad I didn’t have to go through the things they did.

Joe Reiff wrote a book about guys who risked their lives and their careers to try and get the Methodist Church to see some sort of reason about the integration issue. I knew some of those guys but knew more of their children. The idea that society, my society, could be and sometimes was unnecessarily cruel to people for arbitrary reasons became part of my DNA and remains as such. People die because the people around them are cruel. That’s just a fact of life and there’s a very basic part of me that wants to fight against that.

Andrew Libby, who is very gay, once introduced me to his friends, saying, “Boyd isn’t gay. He isn’t even any fun.” I’ve always tried to live up to that. I don’t think I would ever be any good at being gay. If you asked my wife, she’d probably tell you I wasn’t all that great at being straight, either, which is probably why I’m no longer married. Truth be told, the only way I’ve ever been able to express any passion was with my words, which was a pretty big secret for most of my life. You see the problem. The one way I can express myself is one I have almost never used. That being said, I’ve written letters of love that would make you cry. One or two people reading this might have received one somewhere along the way. It did make them cry.

Nobody at my high school said they were gay. There are people who admitted to it later in life, but nobody I knew before I turned eighteen said they were gay. Just nobody. When I was at Millsaps, I knew pretty much everybody, but I knew precisely four people, including professors, who were willing to say they were gay. I never thought a thing about it. I assumed there just weren’t that many gay guys in the world. I dunno where this aids stuff was coming from, but it wasn’t coming from Jackson.

I had an epiphany one day. That’s a big word that means I was gifted with understanding from an outside source. It made me see a truth that was always there, but I could never see it.

There was a guy I talked to quite a lot, with whom I resonated very deeply on an artistic level. That never happened to me before. I wasn’t supposed to be an artist on any serious level. My mom and dad thought that was an unsafe and unsuccessful way for me to live. Finding a guy who I could talk to for hours about stories and characters and words, words, words, changed my life. It really did.

I suspected my friend was gay. Everybody did, but he never publically said he was. In those days, a lot of guys never did. He lived and died without ever coming out. He had some bullshit lavender story about a girl that broke his heart when he was nineteen, and that’s why he never dated or got married, but everybody knew it wasn’t true.

It never bothered me that he was gay. It was many years before we ever talked about it.

Learning that I could like a guy, really like and admire and respect a guy, and not give a shit that he’s gay wasn’t the epiphany, although that was part of it. This was somebody I cared a great deal about on a very human level. I cared about his feelings of happiness or sadness. I cared about his sense of accomplishment. I cared about him feeling included wherever I felt included. That still wasn’t the epiphany.

One day, we were talking about a guy we both knew who had died a few years before. They were both members of my church, but more than that, they were fixtures in the artistic community in Mississippi for most of my life. I knew they knew each other and were friends, but I never thought any more about it. We talked about this man, first on an artistic level, but as the conversation wore on, it became more about their personal relationship, their time together as friends.

As he told me about his relationship with this other man in very basic and simple ways, I noticed that his demeanor had changed. His very completion had changed, and this was no longer a conversation about friendship and art; it was a conversation about regret and the emptiness that comes from loss—the loss of someone once loved.

A tear came to his eyes, and I realized that he loved this man. He loved him in the same way that I ever loved any woman in my life, but even though I was his friend and I was the only one in the room, he still couldn’t say that he loved this man because having people know that he was a man who loved other men might destroy his career or his life, and that—that was the epiphany.

It wasn’t fair that I could tell the whole goddamn world who I loved and how and when and take photos of us dancing and kissing, and nobody would care, but he couldn’t. He lived his whole life without being able to tell, even the people who absolutely supported him, what he was, how he felt, and how he lived. Even now, I can write about this, but I can’t mention his name because I respect him, and I respect his feelings, even though he’s not with us any more, and if he didn’t want to ever say he was gay, I won’t either.

Homosexuality wasn’t a bunch of mustachioed clowns dancing around in leather outfits like in the movies. Leather outfits aren’t something I’m all that interested in, no matter who’s wearing them, even Mia Sara. That’s not something I could ever really understand. Homosexuality was two people who loved each other the same way anybody else loved anybody. Two people whom I admired and respected loved each other, and that I could understand.

They call people like me LGBTQ+ allies. I’ll accept that. I’ll never be part of that community. I’ll always be that guy on the outside. I’m on the outside of a lot of communities. I’m ok with that. From the outside, though, I can see pretty clearly when there are attacks on their community, and they’ve been coming pretty frequently lately.

“Social Justice Warrior” is kind of a bullshit phrase meant to demean and discourage guys who think like me. I get it. I really do. Life would be a lot easier and a lot more fun if we just didn’t think about or talk about these things. On another level, though, justice and fairness are pretty much a baseline measure of civilization. We have to be able to offer it to everyone, no matter if they don’t look like us, act like us, or feel like we do. I’ll be an ally. I’ll gird my scabbard when the innocent are denied the same privileges I have. I’ll probably be pretty cranky and not terribly handsome about it, but that’s ok too.

As I write this, there are people I greatly admire in Charlotte, N.C., sweating blood to try and work out a decent and equitable way for the United Methodist Church to go forward and come to some loving and Christ-like conclusion to the issue of homosexual Methodists. I can’t help them. I would if I could. It’s not easy for a guy like me to admit he’s absolutely powerless in situations like this. I’m with them, though; my heart and prayers are with them. I’d like to turn the page on this in a way that honors the men I knew who could never publically be what they were. I’d like to go forward knowing that the United Methodist Church won’t turn anyone away, especially people who just want to love somebody. Hopefully, that will be the outcome.

As a Mississippian who had to move to Minnesota, to the other end of the river, to be able to say, "I'm a gay man," I so appreciate your words. I often wonder who I would be today if I didn't have to leave home 40 years ago and could have said aloud to my friends, my church, and my family, "I am a gay man." I grieve that loss.

Loved this and you've expressed many of the same feelings that I, a straight white woman, have felt in re: LGBTQ+ issues. Thanks!