Whatever Happened To Fay Wray?

my friend the movie star

The Mississippi economy was much stronger in the years after World War II than it was before. The Office Supply Company added three new locations in Mississippi and two in Alabama. Interstate School Supply Company expanded to Arkansas in the West and Florida in the East.

In Jackson, Mississippi, an expanding economy and the availability of federal money for civic projects like schools, parks, and libraries started making the local economy and culture look like something different from what we had before, even though there were arguments over who could, and who could not, use these new civic resources.

Before the war, North East Jackson was mostly hills, swamps, and a few large farms. After the war, it was the place to be, although its growth came at the expense of West Jackson, which had been the previous boomtown. We didn’t know it yet, but between middle-class families moving to North Jackson and working-class families moving to South Jackson, West Jackson, as developed and beautiful as it was, was doomed.

Most of the new architecture in Jackson was mid-century modern, with sharp lines and gleaming use of glass and other modern construction materials. The Northside Library, a satellite of the Jackson-Hinds Library system, was something to be proud of. Beautifully landscaped, it served all of the booming North East Jackson. For a brief moment, it was where most white Jackson teenagers met their drug connection, but the parents cleaned that up pretty quickly. The Northside Library was a community hub in that rapidly growing part of town for almost forty years.

When white flight started killing Jackson, it took the Manhattan area with it, and with that went the Northside Library. Renamed the Charles Tisdale Library for the longtime publisher of the Jackson Advocate newspaper, it wasn’t the Tisdale Library very long before a mold infestation forced the library board to abandon the building and much of its collection. That’s me telling the end of the story before I’ve told the beginning.

The Northside Library was a pretty safe place to drop me off alone as a child for a few hours. I loved roaming around the stacks and was well-versed in library etiquette. Besides, the woman in charge of the Northside Library was in Junior League with my mom.

Reading Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine as a child gave me a sense that the people who made the movies had a life outside of the movies, and after the movies. It also gave me the sense that many of them were dying off. One year, they published an article about how Lon Chaney Jr. died, and then a few months later, Bud Abbot died, too. I started developing a desire to get to know some of these people as human beings while I still could.

Before the internet, the place to start research was the Card Catalogue at the library. The Card Catalogue at the Northside Library led me to “The Collector’s Guide to Autograph Hunting,” which came in three volumes. While each of the books had a couple of pages on how to maintain and display your autograph collection, they were mostly just page after page of where you would write to the movie stars and ask for an autograph.

Although I have some displayed in my home, I was never that interested in actually having autographs. What interested me was the idea of writing a letter to the people in the movies, having them read it, and then possibly write me back. That, to me, seemed like a genuine human connection, even though it was a brief one, and it seemed like a worthy way to express my admiration for their work.

One of the first people I wrote to was Yvette Mimieux. She was the blonde Eloi in the movie “The Time Machine” by George Pal. Although it didn’t occur to me, she was also the closest to my age, even though she was twenty years older than I was.

Born to French and Mexican parents, Mimieux dyed her hair blonde and decided to become a movie star. She auditioned for the Hungary-born producer-director George Pal, lying about her age. In 1960, there were laws about how long you could make actors under the age of eighteen work in one day. There had been pretty bad abuses of child actors before. Mimieux lied about her experience as well.

Photography had already begun, and Pal began to realize just how terrible an actor Mimieux was. Since she was supposed to play a backward character, he figured he could make that work, but once he found out her real age, he couldn’t get around the child labor laws. His solution was to drastically cut the scenes with Weena in them or assign her lines to other actors playing Eloi.

A little bit of a Hollywood miracle happened. Mimieux got old enough to work as an adult, and in the meantime, she worked her ass off to learn how to act. She got so good that George Pal went back and re-shot some of the scenes he cut because she performed so poorly.

Mimieux’s performance in The Time Machine impressed the industry, so she immediately went into filming for “Where The Boys Are.” Marketing for “Where the Boys Are” might lead you to believe it was just another beach picture. It was anything but. Billed as a comedy, “Where the Boys Are” was mainly a movie about what terrible people the boys were. It featured a hit song by Connie Francis and is still credited for the idea of college students spending their spring break in Florida.

The first time I saw the movie, I didn’t understand it at all. Something happened with Mimieux and her boyfriend that I didn’t understand. Maybe he beat her up or something? Later viewings as an adult made it pretty clear that she had been raped during her spring break. While some of the other girls got boyfriends as they went back to college, she got that. That’s quite a lot for an eighteen-year-old actress in 1960. It’s said she became difficult to cast after that.

Writing to Mimieux, I didn’t say anything about any of her other movies besides “The Time Machine,” mainly because I didn’t know anything about any other movies, or much care. I also didn’t take into account that it had been sixteen years since she made “The Time Machine” and was still a working actor, even though she mostly had moved to guest spots on television by then.

I got back a manilla envelope with a short note saying “Thanks for writing” and an eight-by-ten autographed photo of a teenage Mimieux menaced by an older Mexican wrestler in a Morlock mask. I was probably more interested in the Mexican Wrestler wearing the Morlock mask and blue paint, but this was my first interaction with a movie star by mail, and I was pretty full of myself.

I’d met performers before. I’d met Big Bird, both in and out of costume, but this was something I had done on my own, without my parent’s involvement, so I continued. I wrote Vincent Price, Christopher Lee, Ray Harryhausen, Ron Ely, Doug McLeur, and more. Sometimes, I got a response, and sometimes, I didn’t; any response at all was thrilling.

The autograph book had an address for Fay Wray in Culver City. King Kong was by far my favorite movie. It still is. Fay Wray was the last surviving member of that company. My letters to Culver City got no response. Then, one day, all three came back with “address unknown.” The main movie star I wanted to reach, I couldn’t.

I got older. It became pretty clear that my dream of working in the movies or maybe making up stories that could be movies was pretty stupid, and I needed to get more serious about life. My grades sucked, and I wasn’t getting along with my headmaster, but I had a girlfriend and looked old enough to buy beer just about anywhere. I gave up on anything having to do with movie stars.

Most people thought I had given up on my dream. That wasn’t entirely true. After college, I started making trips to Hollywood every summer to meet with whoever I could. My keys to the kingdom were that Forrest Ackerman allowed anybody who showed up into his home on Saturdays, and he was surrounded by a community of boys just like me who held onto the dream. A lot of them found work at the Don Post Hollywood Mask Company, which opens up a whole new line of stories.

Mentioning my story about Mimieux and Fay Wray to one of Forry’s monster kid friends, one of them said I should try a Beverly Hills address for Fay Wray instead, and he had it in his pocket organizer. At twenty-seven years old, when I got back to Jackson, I tried again to write to Fay Wray.

I received a personal stationary-sized envelope from New York, thanking me for remembering her, signed by Fay Wray.

Being older, I learned a few things since my first attempt to make contact with Yvette Mimieux. I decided that Fay Wray probably was sick to death of people asking her about King Kong. She made almost a hundred movies in her career, so I resolved to learn something about them. Her first major role was in a film called “The Wedding March” with Erich Von Stroheim. I also thought that if she engaged with me at all, I should look for opportunities to ask about her life outside of Hollywood.

She had written an autobiography called “On The Other Hand,” which the Northside library didn’t have, but the downtown library did. What I learned from that was that she was a simple country girl from Canada whose family fell apart, so she ended up being passed from cousin to cousin as a teenager in Hollywood when a photographer “discovered” her at sixteen, and she began to get jobs as a dancer in silent movies.

Fay never had much luck with men. Her first two husbands had addiction issues. The first was addicted to heroin. She even woke up one night to catch him trying to inject her while she slept. I suppose he thought if they were both addicted, that’d make things better. It didn’t. Her first husband wasn’t very faithful and often vanished for extended periods.

Many men pursued her. Often powerful and rich men, but she was faithful to the husbands who weren’t faithful to her. Howard Hughes made several attempts to woo Fay, but she rejected him. One night, on a long train ride from New York back to Hollywood, Fay Wray agreed to meet Howard Hughes in his private car, not knowing where her first husband was or when she’d see him again. He didn’t continue calling. She didn’t much care.

So far, my connection to Fay Wray was entirely through the mail. She was remarkably personable. Her third husband, a doctor, was a gentleman. Although he had passed, too, he provided her with a comfortable retirement. The address in Beverly Hills belonged to her son, who forwarded my letter to her. She was in New York with her daughter, who was trying to make it as an actor, like her mother, and a writer, like her father.

I wanted to do something special for Fay on her ninetieth birthday. I hadn’t known many people who turned ninety, but both my grandmothers passed that threshold. In those days, you could still get autographed copies of Eudora Welty's books in Jackson without breaking the bank. The supply would soon dry up as Welty had quit signing. She would be turning ninety herself pretty soon.

I found a signed copy of “Losing Battles” at the Choctaw Book Store. I wrote a long letter about how much I enjoyed talking to her and boxed it up to Fay Wray’s New York address.

Every time I wrote to her, I knew it might be the last time. She was getting older, and I didn’t have any real connection to her other than being a fan who said how much he enjoyed “The Wedding March” instead of King Kong. It was a lie when I said it. It took a while to find a company that had it on VHS. Silent films are something of a specialty market. If she never wrote back, I would be satisfied. She owed me nothing, and she’d written four times by then. Besides, the entire point of the thing was me reaching out, not her reaching back.

One day, I got a phone call while I was shaving. I was used to little old ladies calling me at home. Friends of my mother. Friends of my grandmother. Women associated with Lance Goss or Millsaps. Hearing the voice of a little old lady I didn’t recognize wasn’t unusual.

“Boyd, This is Fay Wray.” She said, with a bit of a chuckle.

I had to sit down.

It turns out she was a particular fan of Eudora Welty. They had met once at a dinner, where she sat with Lauren Bacall and Eudora Welty. A photographer took a picture of them. She had a copy somewhere. If she could find it, she’d send me a copy. She’d made a movie once about Natchez with Leslie Nielson and Debbie Reynolds. She played the mother. None of it was shot in Natchez, though. I was a bit shocked about how much she knew about Mississippi. It turns out Mississippi was a lot more like the area where she grew up than Hollywood. We talked for over an hour.

She gave me her phone number. This is serious, I thought. We began talking, fairly regularly.

Something about turning ninety re-ignited interest in her career. “I don’t know why they’re making another movie about the Titanic.” She said. James Cameron had reached out to her to offer her a role in his troubled production of Titanic as “Old Rose.”

Fay had written a play about her mother’s life in Canada, and that summer, her daughter was directing it at a small theater in Upstate New York. Having a chance to work with Vickie on a play about her grandmother meant considerably more than being in yet another movie. Fay suggested Gloria Stuart, who was a year older. Stuart accepted the role. Fay never considered not being in “Titanic” as a missed opportunity, but she would have considered not being involved in the Vickie Riskin production of “The Meadowlark” as a very serious oversight on her part.

More offers would come. Peter Jackson had a contract with Universal Studios to remake King Kong. He offered Fay a part delivering the “it was beauty that killed the beast” line, which she agreed to do, but then Universal pulled the plug on the production when Sony announced “Godzilla” and Disney announced “Mighty Joe Young” for the same summer. The project gained new life after “The Lord of the Rings.” Jackson tried to get Fay to commit to recording the line, in costume, in front of a green screen so he could inject it into the film, but her health wouldn’t permit it.

I never discussed “King Kong” with Fay Wray. I considered it a cardinal rule of our friendship that I wouldn’t ever reduce it to that. She did reference him once when she said, “I’ve buried three husbands and King Kong, you know.” I figured that was about all that needed to be said.

September 11, 2001, I knew several people living in Manhattan. They were all considerably younger than Fay Wray. Knowing where her building was and where the World Trade Center was, watching the first and then the second tower crumble, my mind screamed with thoughts of “Fay!”

Phone lines in and out of New York were hopelessly jammed, not by the terrorists but by Americans trying to contact loved ones. It would be more than a week before I could reach Fay or her daughter. She was fine. Having lived through so much, she was probably more stable emotionally than the rest of us. Still, knowing a little old lady just blocks from the attack made the entire experience different for me.

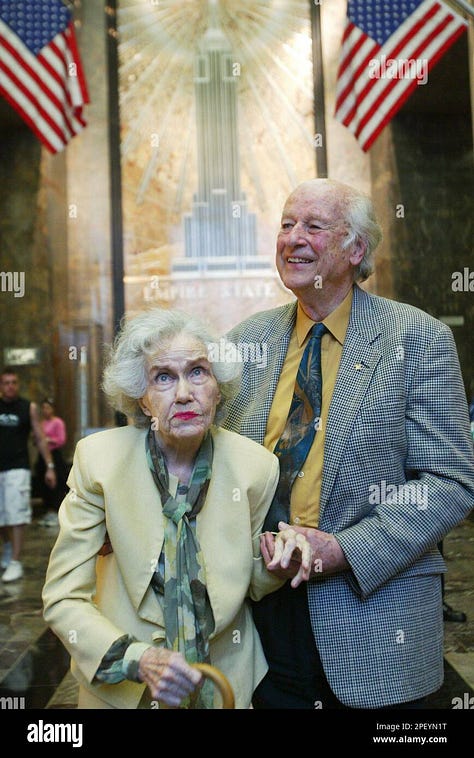

A few years later, I heard from Ray Harryhausen that he had been invited to take a trip to the top of the Empire State Building with Fay Wray. No one was saying it was her last trip, but everybody was thinking of it. Harryhausen and Wray had been friends since the forties. He would be an appropriate escort. I was not invited to the trip to the top, but I flew to New York anyway, just so I could be near it.

Two months later, Fay Wray passed from this world to the next. Soon after came Ray Bradbury, Forrest Ackerman, and Ray Harryhausen.

Whatever happened to Fay Wray? She had a pretty good life, all in all. She had love and loss but found somebody who stayed with her no matter what. She had children and friends and a life on both coasts and Canada. She had friends far away in Mississippi and all over the world.

Whatever happened to Fay Wray?

That delicate satin draped frame

As it clung to her thigh

How I started to cry

'Cause I wanted to be dressed just the same

She actually knew she had become a gay icon, and had even seen a VHS copy of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” It wasn’t her kind of movie. “It wasn’t Shakespeare,” she liked to say. Still, it was nice to be remembered.