Which Stories Are Real?

Every coming-of-age story features a struggle between socially aware people and those who are socially conscious. So, what do I mean by that? Aren't they the same thing?

Some people are chronically aware of some imagined social hierarchy, their place in it, and, more importantly, YOUR place in it. They're motivated to maintain the order and strata of this social order as a part of their daily existence as a matter of self-preservation. They're the ones who go to the prom with somebody they hate because they're popular.

These characters come into conflict with other characters, usually the heroes of the story, who are socially conscious. These people don't put any importance on social stratification. They're motivated by social structure and interactions' impact on the individual, their needs, and supposed "happiness."

These are the people who take their ugly cousin to the prom because nobody else will. That never happened to me. Partially because I don't have any ugly cousins, but more than that, I was usually obliged to ask whoever I was currently and regularly seeing.

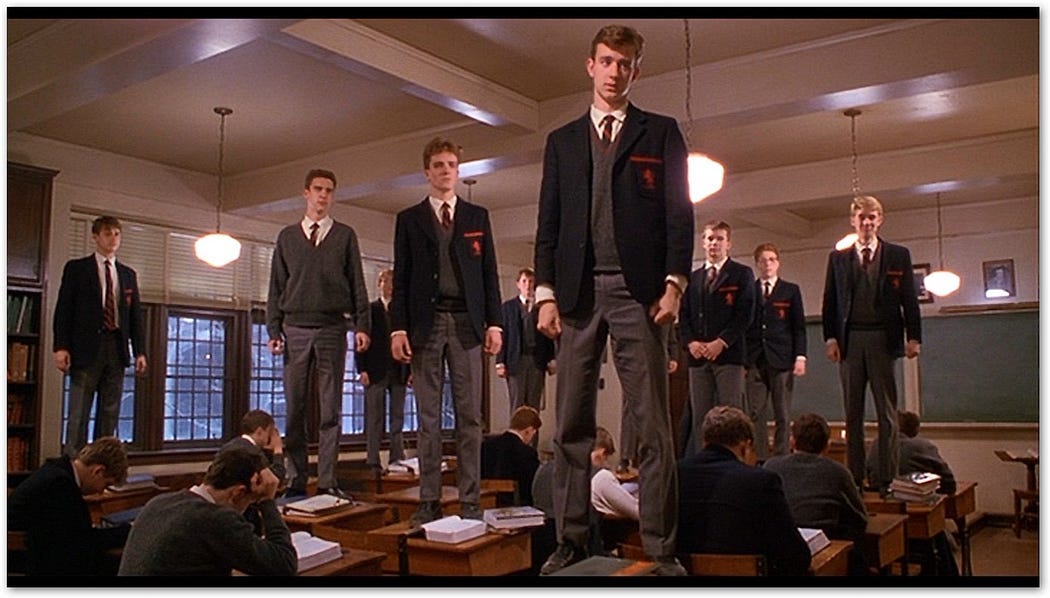

In some stories, the stakes are pretty high. In Dead Poet's Society, the good-looking kid dies, and the teacher gets fired, but everybody else learns to stand up to the asshole principal. In Fast Times at Ridgemont High, the nerdy guy gets the girl. Breakfast Club tries to say that these divergent social motivations can come together and be friends, but I always wanted to revisit those kids in six months to see how well their new alliances held up.

Most of these stories are written by people ten or twenty years away from the coming-of-age part of their lives, and they're most likely really writing about how these motivations play out in the adult world. They reflect on the conflict between the young lawyer who goes to all the "right" parties so they can get rich clients and the young lawyer who sues the big company poisoning the water in a poor neighborhood and gets rich that way.

Life usually isn't that simple. Everyone worries about where they fit in, is aware of those who are less fortunate, considers themselves better than some imagined "other side," and worries that others don't recognize their imagined moral superiority.

There are evolutionary rewards to both competition and cooperation between social forces. Evolution tends to squeeze us from all sides at once, which is probably why most of us feel like we can't ever get a break in life—that it's all just pressure and more pressure because it is. That's how evolution works.

I think most of this boils down to memes—real memes, as they were initially defined, not gifs of cats, which is how the internet has come to define them. Memes come together to form the structure of stories, and stories are how we make sense of the world. Even though stories aren't necessarily "true," they provide us with a structure by which we can satisfy ourselves that we know what is true.

For instance, in Dead Poet's Society, the structure of the story tells us that the boy dies because his father tries to make him go to medical school when he really wants to be an actor. Because of the structure of the story, we're satisfied that we know "the truth." In reality, though, a teenage boy who takes his own life is vastly more complicated than just "his dad's an asshole." Among the people who were teenagers when I was a teenager, we've spent forty-five years trying to figure out why the people who chose to leave us did what they did, without any real consensus, other than "they were too young," "they never knew how much we loved them," and "if only I'd talked them out of it."

Stories don't have to be real to feel real. You can spend your life trying to understand the truth of a ten-minute story. Memes provide a structure by which we can satisfy ourselves and understand what happens around us, whether we do or not.